Robin Hauser, director and producer of the documentary film, CODE: Debugging the Gender Gap, on how diversity equals innovation, made a new film, Bias.

impactmania spoke with director Robin Hauser about her biases, funding model for her films, and how the posse effect would retain more women and minorities on a board.

BY PAKSY PLACKIS-CHENG

Robin, congratulations with the latest film Bias.

Thank you, it’s been fun. I am in Seattle right now. The film screened at Microsoft yesterday and I’m screening at Amazon today.

To screen the film is probably the first step toward starting a conversation. Is this an opening to in-depth work for companies or do you find a lot of companies ‘talk the talk, but don’t walk the walk.’

I think the ‘talk the talk, but don’t walk’ the walk is true. I applaud the companies that are willing to have the film. The film is not accusatory; the premise is that we all have bias, because we’re humans.

How does being bias affect us and are you willing to look inward and figure out what role bias plays in your life? And how does it affect you socially and in the workplace?

Do companies then follow-up with workshops? Or how does that play out after you leave? Any idea of what goes on internally?

That’s a good question. A lot of these companies have a mission to do some sort of unconscious bias training. Whether it’s through a consulting company or by in-house staff. Many companies are buying this documentary as a starter.

This film is entertaining, but also informative. When you mentioned to people that they have to go through bias training, people often rolls their eyes and say, “Here we go again.” But if you say, “I’m inviting you to a movie, the company executives are going to be there. Please join the conversation.” The audience will be more curious and realize that this isn’t such a burden to learn about.

You mentioned trainings. I asked the Intel’s Chief Diversity Officer about recent research that has shown that training is not all that effective.

I’ve heard that too. I think there are a couple different reasons. In certain cases, training can make people become self-conscious. I had one female manager say to me, “I never thought that people think differently of me because I’m a female manager.”

In those cases, it’s because the training’s not done well. You should never leave people without a takeaway or some understanding of how to move forward. The documentary Bias is not a solution to unconscious bias—it is a conversation starter. You don’t want to let people off the hook by saying, “Look you’re human, you’re going to have bias tendencies.”

Historically, we had to be suspicious of people that seemed different than us, that acted differently than we do. How is this useful in the modern world, where we’re not living in as much of a segregated society, where we’re expected, especially in the workplace, to be with people from different cultures and work together?

Today’s work society is almost the opposite of our tribal origins where if the others were dominant, it would mean less food for us. But now if we’re trying to solve complex issues, it is in our favor to work with others that are different.

That’s exactly right and really important. If you bring in different ideas, if you’re open to having different points of view, we have seen that that type of diversity in design groups and in upper management actually makes a company better because you’re able to design a product that serves a greater breadth of humanity.

I’m working on impactmania’s next project with the Neuroscience Research Institute (UC Santa Barbara), Human Mind and Migration. In your assessment, or maybe people you’ve interviewed, do human brains get rewired after they are dealing with reassessment of bias?

Yes, we have interviewed people that have studied the brain science behind bias. We talked to David Rock at the NeuroLeadership Institute in New York and people in Barcelona, Spain who research the brain. It was really interesting and really important for us to approach it from that perspective. Neuroscientists learned that one way for us to mitigate or to change some of our biases is to have an intimate experience with somebody that’s different than us.

Imagine in a workplace, if I am uncomfortable around anybody who’s foreign, because I think that they might be terrorists. Suddenly, I have to do a project with someone who is Muslim. We work together for a month. I realize my perspective on what it means to be Muslim has changed. I’ve realized that I have to approach every person as an individual and not to classify and categorize people based on religion or skin color or gender.

We’d have to expose more people to situations where they have to interact with others?

That’s exactly right. And, of course, you have to approach that with an open mind.

What else could we do to intervene if we are prewired to act on these impulses?

I think becoming aware of it. One of the fascinating things I learned is that even though we all have bias, we don’t have the ability to recognize our own biases. I might know that I have a bias against dogs, for example. But I don’t know all the biases that I have in me that I’m not aware of, right? What’s fascinating though is that we see bias in other people really easily.

When I talk to people on the street interviews and I ask, “Do you consider yourself bias?” Ninety-nine percent of the time, people say, “No! I really work hard at being open minded.” Or “I think I’m very fair.” Then I’ll ask, “Great, what about your friends and family? Are any of them biased?” I usually get, “Yeah! My God, yes!”

When you ask what kind of bias. They’re racist, sexist, or are political bias. It’s fascinating that we can’t see it in ourselves. Learning about unconscious bias and becoming aware that it lives inside of us is the first step, because it definitely makes us think differently in work places.

One male manager emailed me to thank me for an eye opening film, “I never stopped to consider that there were only 30% women on my team.” Other people have said to me, “After watching your film, I realized that in meetings, men speak over women all the time. There are certain people whose voices aren’t being heard at all. I didn’t realize that was happening.”

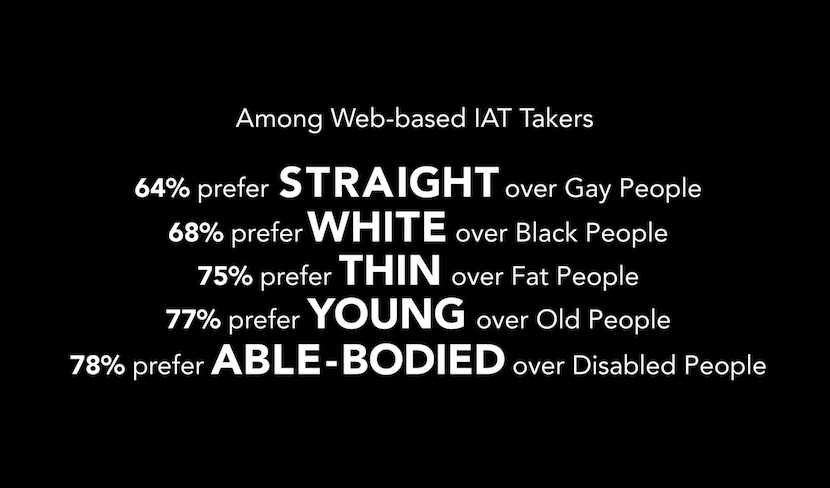

You took the Harvard Based Implicit Association Test and were shocked by the results. What are some of the biases you held?

I consider myself a feminist and equal about men and women. I showed a strong association of women and family versus men and family. And I show a strong association for men in career versus women in career.

That surprised me, because I’m a working woman. I grew up with a mother who did tons of important volunteer work, but didn’t have a paid job. I grew up in a very traditional household and I gave up my career when I raised my kids.

Even though I firmly believe that a woman is capable of being in the work force at any level and position, I hold a covert association, apparently of women being with family and men with career.

I grew up in a very white part of San Francisco, when I did the risk association—I show a moderate association for black Americans and harmful objects as opposed to white Americans and harmful objects. By the way, both blacks and whites tend to have that association, but it’s not an excuse.

What do you do knowing this about yourself?

What I’m trying to do is become more empathetic. What could it feel like to be one of few people of color in the room? I’ll try to make an effort to include and not marginalize.

If somebody larger or potentially threatening was walking down the street, I might change sides of the street. Do I have any facts to justify that behavior? If I’m protecting myself because somebody was knocked down that street a day ago, okay. We need to be smart about that. But if there’s really no reason to justify that behavior, I stay put.

I interviewed African-American men who said, “People change sides of streets all the time when I’m walking by.” And “When I walk into an elevator, I see women clutch their purses.” They see women pull their children closer to them.

Bias toward minorities and women is also a theme that was discussed in your film CODE (2015). Has there been an increase in the numbers of women and minorities in science and tech since we last spoke?

Those numbers haven’t changed much. What’s interesting is that even with an effort to bring in more women, more people of color into a space like tech, which is predominately white and male, we’re not doing enough to include those people once they’re in the workplace. The retention levels aren’t really impressive. We’re still getting orders for CODE, it’s because it hasn’t dated itself.

I interviewed the Chief Diversity Officer at Intel. Intel is investing $300 million dollars into diversity programs. Their new hires diversity mark is 45 percent of the workforce. Yet underrepresented minorities are only 13.2 percent of the total workforce. Even if you hit high on hiring a diverse workforce, there is a retention issue.

Right, and that is really an inclusion issue. Why would you want to stay some place when you don’t feel included?

What have you seen that has worked in companies to retain a diverse workforce?

There is something that was called the ‘posse’ effect. Rather than bringing one woman or one person of color onto a board or into upper management, it’s this idea of bringing in a group or several people. If suddenly there are three women on a board out of ten—which still isn’t enough—but then the women feel less like ‘The One’ or ‘The Only,’ right?

The companies have seen that retention is better, tech companies especially, when they make an effort to bring in a posse—a group.

I’ve never been one for quotas, but I’m beginning to change my mind. I applaud it, because it’s not happening on its own. The only way to do it is to mandate it.

It should be more than one by the way. There are so many incredible women. Now here’s the challenge, many of these boards have strict rules about who qualifies—ten years in the C-suite or something. Since we know women don’t rise up to the top levels in companies very easily, there are fewer women to pick from.

They’re going to have to change the criteria to be on the boards at these big companies. The only way to get more women into upper management, more women in leadership, is by having more women in the boardroom.

That and more women funders, right? The number of female-led businesses that are funded is dismal. In 2017 it was 2,2% of the total investments by venture capitalists (VCs).

Let’s talk about funding a film. You made three feature films and one short film. What does it take to get a film funded?

I have an unconventional way, in terms of the documentary world, of raising funds. Coming from business, it seemed like an obvious way to fund a film. I get a lot of funding from the corporate world.

I’m very careful about two things:

- I don’t want just one corporate funder, because I don’t want it to look as though a company influenced the film. You can imagine if I made a film about oil and I had Exxon as a sponsor. Bias has 14 different corporate funders. They’re not investors, they’re donors. All of them give me money before they’ve seen the film.

- Every one of them signs an agreement with me saying that they have no creative control over any content in the film. They do have the right, once they see them film, to remove their logo.

I have raised funds from Silicon Valley Bank, JP Morgan Chase, Deloitte, Adobe, Dell Technologies, Gilead Sciences, and Ericsson. These are companies that care about this issue. They are not claiming to have solved any of these problems. They want the film to get out there, because they know how important it is for the workplace.

It’s really hard to make a profit from documentary films. Sadly companies like Netflix and Amazon won’t pay the same amount for a documentary film as they would for some film with drugs and sex.

Do companies like Netflix license the film or do they pay per view?

For CODE, Netflix licensed it for two years. They paid me a certain amount of money—which was very little—to license the film for two years. Amazon, iTunes, Hulu, they pay royalties per screening.

Private screenings of the film are needed to keep my production team and myself alive. This film cost me a million and a half to make.

I’d like to get the film to communities, schools, and colleges that typically can’t afford my honorarium. That’s why it puts the pressure on me to get paid screenings so that I can afford to get to schools and places that I think are important to get to but can’t necessarily pay for it.

Considering all your stories, what is the thing you hope people walk away with? Why is Robin making all these films?

I believe in giving back and do something with my time on Earth. I want to feel proud about what I’ve contributed. With these films, I want to open up people minds and maybe have them think about something a little bit differently. I’m in cause-based stories and films that help people look inward.

Where is that coming from?

I’m sure it comes from my parents. Both my parents are very philanthropic and hard workers. It’s offering their elbow grease and their time and their resources. They’ve given back to the schools they’ve gone to and to wonderful organizations like the local hospitals and the Red Cross.

What other stories are you going to tell in the future?

I believe that there’s a story to be told about financial literacy or illiteracy in the United States. How much do we really know about how to handle money and what to do with money, especially for women.