The new impactmania and UCSB program Human Mind and Migration (HMM) serves as a platform for meaningful broad-based engagement to take place, considering the present historical moment and the sociopolitical and environmental cocktail of issues related to migration. We are featuring migrants who have been contributing cultural, social, and economic wealth and health to their adopted countries, as well as news related to the different mass migrations occurring world-wide.

Add your migration story to the HMM program: www.hmm.ucsb.edu.

BY NATALIE GOMEZ

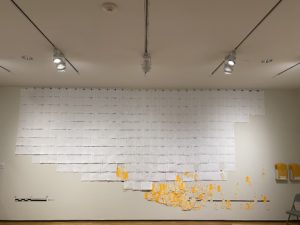

On their first Friday back at UC Santa Barbara after returning from Winter Break, a group of student-interns walked into a new exhibit they were assigned to facilitate at the Art, Design & Architecture Museum. Skylar Lines, a 20-year old from Napa, California, gawked at the large wall immediately apparent from the entrance — remarkable not for its artistic extravagance but it’s blankness.

As a third year student majoring in the history of art and architecture, Lines was trained to know that this bare wall, systematically covered with a series of white printer papers each denoting a large letter and number, would normally be the focus of any installation.

And, in only a few hours, the museum would hold its Winter Opening Reception for wealthy donors to come get an early access look at what their money has contributed to. Staring at this grid-like image, she mumbled to her peers, “Shouldn’t the exhibit be finished by now?” But as she was forced to move deeper in the room to make space for the other interns, circling around the large tables at the center of the gallery, she caught sight of the collage made of clearly worn, dirty t-shirts pinned around the doorway she had just passed through, opposite from the main wall, and a spark of understanding shone in her eyes.

“This is history,” Lines said she remembered thinking. “Not just any ordinary art show.”

As Lines and the other museum interns would soon learn from the visiting head curator himself, UCLA Professor Jason De León, those t-shirts on the wall are just some of the objects left behind by the millions of migrants who have attempted to cross the deadly Sonoran desert of Arizona, known for its extreme heat and dryness, in search of a better life. They were all part of the art installation in front of them called Hostile Terrain 94.

Jason De León in front of t-shirt collage with UCSB student-interns in the background. Each shirt was personally collected from the Sonoran Desert of Arizona by De León.

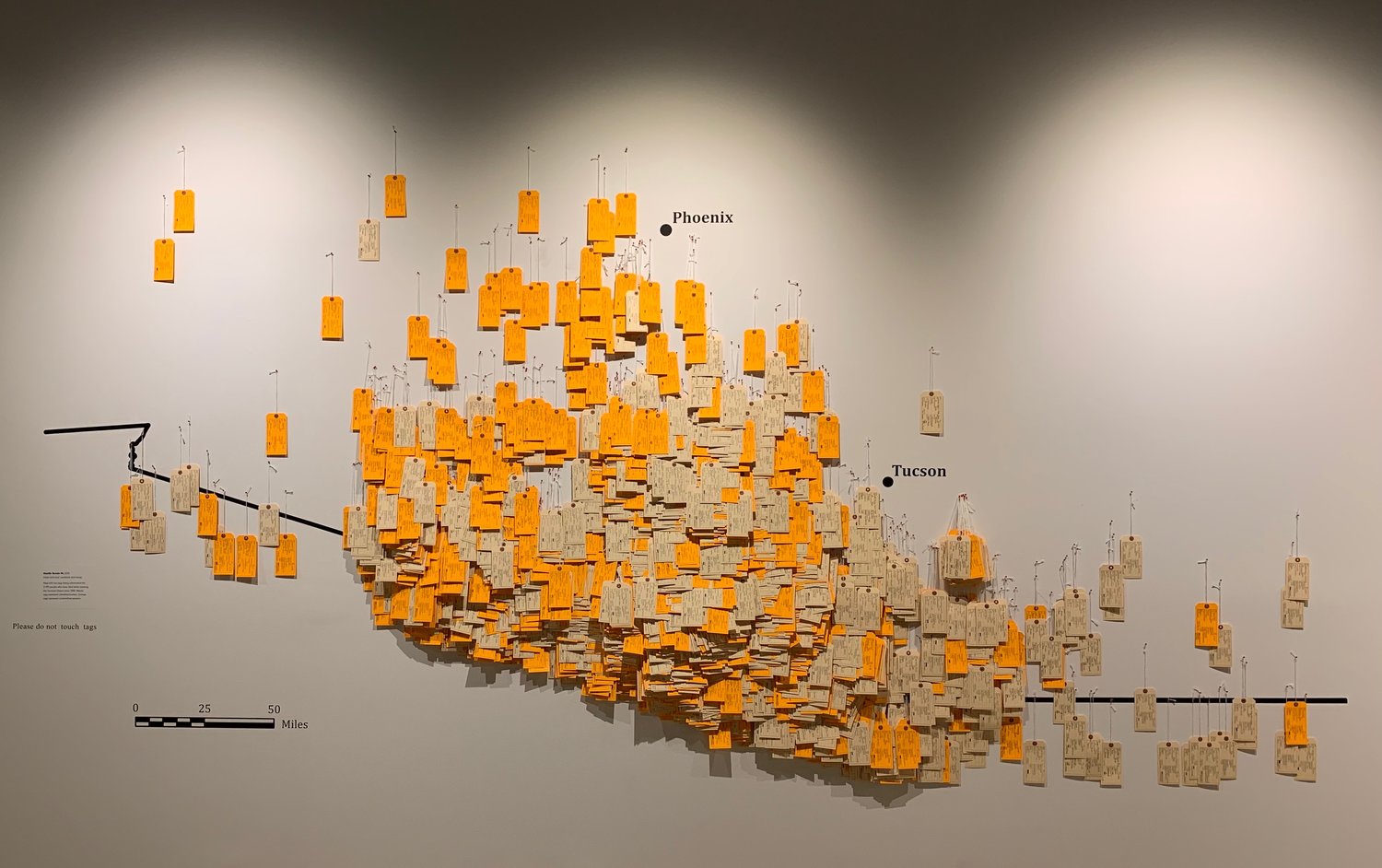

Hostile Terrain 94 is global pop-up exhibit put on by the Los Angeles-based non-profit organization the Undocumented Migration Project, founded by De León in 2009. The exhibit aims to confront community members with the often overlooked, harsh realities of undocumented migration at the Mexican-U.S. border by requiring the participation of community members to complete the installation — a 25-foot-long wall map of the Arizona-Mexico border with over 3,200 toe tags attached. Each toe tag represents a dead body that has been found in the Sonoran desert between the mid-1990s and 2019 and contains the available and identifiable information of that person — case number, name, age, sex, date the body was located, condition of the body, cause of death and coordinates where the remains were found — which will be handwritten by the public.

Lines, along with this group of interns, would be the first to write these devastating details on the toe tags, kickstarting UCSB’s very own HT94 exhibition which also includes items recovered by De León while he was conducting his anthropological research in the desert. “Writing names is powerful,” Lines said, when reflecting on how filling out a toe tag for a 19-year-old girl really hit home. “The shock invites you to ask, ‘How can I change this?’ and take action.”

Over the next few months, the rest of the toe tags will be filled out by the Santa Barbara, Goleta and UCSB communities and transported to the wall map depicting the Arizona desert at the border. Museum interns and staff will geolocate the toe tags to the exact coordinates where each person’s body was discovered. When finished, 3,200 toe tags will be hanging from red map pins and all paper grids, which correspond to manila folders holding the bodies of that zone’s information, will be gone.

Jason De León and exhibition coordinators, Nicole Smith and Gabe Canter, debriefing the UCSB student-interns on how to run Hostile Terrain 94 exhibition before its opening reception.

Napa, California native Lines was pleasantly surprised that the AD&A Museum was bringing in such a politically charged exhibition to Santa Barbara County, which as of July 2018 had a population of nearly 450,000 people, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. “Institutions like museums tend to stay apolitical in order to please the majority, especially if they are in a relatively small city compared to, say, Los Angeles or San Francisco,” she said. “What UCSB is doing is f—ing ballsy.”

Of Santa Barbara’s population, 85.4% are white and 14.6% comprise other minorities — a staggering statistic until one looks a bit closer. Within Santa Barbara 45.8% are estimated to have Hispanic origins, affirming the area’s diversity and potential stake in the exhibition. Additionally, from 2014-2018, 22.9% of the county’s population reported they had been born in another county and 39.7% spoke a language other than English at home.

Hostile Terrain 94 is currently partnering with over 130 exhibition hosting partners both nationally and internationally, a number that was originally set to be 94 (hence the exhibition’s name) but has steadily kept growing. Gabriel Canter and Nicole Smith, former anthropology students and interns of De León at the University of Michigan, now serve as the coordinators of the exhibition following their recent 2019 graduation. In January, they visited UCSB with De León to help bring HT94 to the AD&A Museum. Canter, who holds a B.A. in sociocultural anthropology, vocalized the exhibition’s main purpose to the student-interns. “To get people to come together, write down the names of the dead, memorialize them and think about the U.S. policy responsible for their lost lives,” he said.

Handwritten toe tags hang as part of the Hostile Terrain 94 exhibition in the UCSB Art, Design, & Architecture Museum. The white toe tags contain the information of bodies that could be identified, while the orange toe tags represent those who remain unidentified.

In 1994, the United States implemented a new border control policy called Prevention Through Deterrence. The policy heightened border patrol enforcement at more populated, urban ports of entry which migrants were historically accustomed to crossing. U.S. Border Patrol officials believed this would discourage individuals from illegally crossing through the more remote and dangerous natural environments left less attended to, such as what they deemed the “hostile terrain” of the Sonoran Desert in Southern Arizona. However, this strategy failed as more than six million people have attempted the journey since the year 2000, with at least 3,200 of the crossers dying along the way.

“We’ve done the exhibit eight times now and each one was in a pretty different region, mostly with different student demographics,” Canter said. “The ways each community interacts with the exhibit is always really interesting to me — and telling of certain political climates.”

Although the exhibition aims to stand in solidarity with migrants across the world, Canter said not every audience has shared this notion. “At one of our earlier prototypes, I had a discussion with a group of students who were filling out toe tags. Most of them were very emotional and telling me about how the project was making them feel. Then, another student disagreed and told us that she did not feel bad for the people represented on the wall because ‘they attempted to cross illegally and knew what they were doing’,” Canter said.

While Canter admits hearing the student’s differing perspective on immigration was difficult, he said he views it as a positive memory as it fostered a space for dialogue. “She was actually very willing to talk about this, not in an aggressive way, and all of us at the table were able to have a really stimulating and emotional conversation,” he added.

Jason De León explaining the significance of each “Migrant Artifact,” objects left behind by crossers in the Sonoran Desert and that were collected by the Undocumented Migration Project, featured in UCSB’s Hostile Terrain 94 exhibition to the student-interns.

With the opening reception of the museum looming closer, Leticia Cobra Lima, the 31-year-old Museum Internship Program coordinator, worried about what the emotional toll might be on her students from encountering and facilitating the exhibit.

“We have a diverse cohort of students,” Cobra Lima said carefully. “The exhibition could produce a vast array of reactions.”

In fact, this was the art history doctoral student Cobra Lima’s main concern from the moment the HT94 exhibition was introduced to her by organizers months prior. Before the installation was fully installed, she was shown an example of a toe tag that produced “a brutal feeling” and “a lot of unexpected sorrow” in her when she saw the crosser was from Brazil — Cobra Lima’s home country.

“The people directly impacted might feel differently than those born in the U.S.,” she said. “Both reactions are important to make meaningful dialogue… but I want to provide them with the help they might need and only allow as much contact with the exhibition as they feel comfortable with.”

Ava Robles, a 20-year-old third year from Pasadena, California, was one of the student-interns with a personal connection to the exhibition. In 1952, decades before the U.S. enacted the Prevention Through Deterrence border policy, Robles’ grandfather crossed the border into California through one of the more frequented crossing points by train.

The photo album, “It’s a Dry Heat” (2009), contains images taken by Memo, Lucho and Ángel during their journey through the Sonoran Desert of Arizona. Featured on either side of the album are women’s repaired shoes (2013) and a black water bottle (2010), objects collected in the Sonoran Desert by Jason De León that were designed specifically for people to cross the border.

The HT94 gallery space features a table of what De León calls “Migrant Artifacts,” which attempt to bring in the voices of real people who crossed into the exhibit. The migrant artifacts include objects left behind in the Sonoran Desert that the Undocumented Migration Project collected, photo albums that migrants themselves have put together from their journey and donated, and audio recordings of interviews conducted with people who have crossed.

For history of art and architecture and religious studies double major Robles, it was the 2009 photo album “It’s a Dry Heat,” which contains pictures of migrants on trains, that affected her the most. “I always understood intellectually what my grandfather went through,” Robles said. “I’m a very visual person, so the images made me truly feel the impact of his journey and that it is not just one isolated event but a mass migration.”

Later that night during the Winter Opening Reception, Robles was one of the interns working the exhibition. “Writing the toe tags is difficult when you really start thinking about the people and their lives,” Robles said, after the fact. “But while helping in the exhibition and instructing visitors I was able to detach myself from my personal connection and explain it well.”

Nonetheless, Robles has yet to return and work the exhibition a second time. “If I wasn’t doing anything else and was asked, I would do it again,” Robles said while looking down at her hands. “Though it has become harder for me to be in there as time has passed.”

Toe tags filled out during the opening reception of the Hostile Terrain 94 exhibition were pinned to the in-progress wall map at UCSB’s Art, Design & Architecture Museum.

The wall map in UCSB’s HT94 exhibition will be an evolving piece as more toe tags are to be added as the exhibition coordinators, Canter and Smith, sift through the updated data downloaded from public government records and send over new information. The United States currently still adheres to the Prevention Through Deterrence border policy, and everyday people continue to risk death by crossing. The policy has since expanded to areas in Texas, where hundreds have perished while migrating through an unpopulated wilderness.

Smith, who holds a B.A. in anthropology, recalls what it was like seeing the HT94 exhibit fully installed for the first time. “There was just a wave of silence that came across the room,” Smith said. “I realized how powerful this exhibition could be. It was really overwhelming seeing the pure density of the tags and just understanding the devastating toll of U.S. policies on human lives.”

“There’s a lot of things going on in the media about undocumented migration, a lot of it sensationalized. We want people to realize that this is not just a headline, but something that real people are suffering through, real people who are dying at the hand of a U.S. policy,” she said. “I hope that people who see HT94 will recognize the urgency at which change is needed, not sit idly knowing people are continuing to die. We all have voices and I hope that more people will use them to speak up and stand up for what is right.”

UCSB is just one of more than 130 locations where the exhibit is opening world-wide leading up to the November 2020 U.S. Presidential Election. During the election year, De León and his team will collect toe tags written by the majority of the host spaces and compile them in an installation in Washington, DC. The result of the show is to be a visual representation of how decisions made by those elected to the U.S. government can lead to mass fatalities and invite others, as UCSB student-intern Lines said, “to take action.”

“Not everything in a museum is going to be an abstract painting on the wall that people just ‘Ooo and Aaa’ at,” commented Lines with a laugh before her face turned serious. “Art can act as a powerful means of political change.”

impactmania’s past interviews and programs have been featured in international media, a number of universities, the UN, U.S. Consulates, and have been cited by Harvard Business School, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, and Duke University Press. impactmania’s Women of Impact program was awarded the U.S. Embassy Public Diplomacy grant (2019).