Who knew that becoming a footnote (four times!) would be so exciting!

The following interview with Robert Zimmermann, Managing Director of the Berlin Phil Media, appeared in 2016 on impactmania. Harvard Business School has cited the interview as a source and four parts of the interview appeared in the book Sound in motion: cinema, videogames, technology and audiences by Álvaro G. Díaz Rodríguez, Autonomous University of Baja California and Enrique Encabo, Professor of Music, University of Murcia, Spain. Sound in Motion is published by Cambridge Scholars Publishing in 2018.

BY PAKSY PLACKIS-CHENG

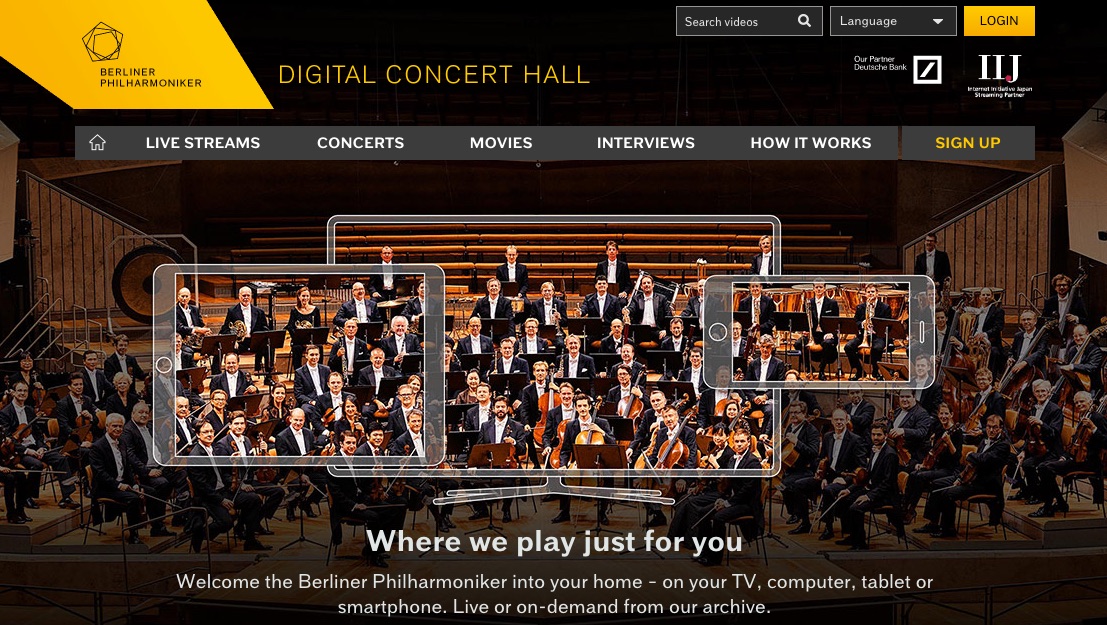

After pioneering the Digital Concert Hall for the Berliner Philharmoniker, Robert Zimmermann, Managing Director of Berlin Phil Media, is now working on enhancing your commute, especially maximizing your experience in your future robot car.

The Digital Concert Hall has been visited by approximately 20 million people in the past seven years. More than 800,000 people have registered, with 5% as paid members.

impactmania sat down with Zimmermann at the office of Berlin Phil Media.

What was one of the surprising learning experiences in building the Digital Concert Hall for the Berlin Phil?

The one important thing we did not expect is the impact of social media. When we started in 2007… Facebook and YouTube were small. WhatsApp and these kinds of communication tools and community-building tools didn’t exist.

[Berlin Phil] clips on YouTube have been watched 45 million times. For classical music that is a lot. And to generate 800,000 Facebook fans you can inform and contact—that’s a very powerful way of keeping in touch with your fan base, and building a community around what you’re doing. It’s very important for the musicians and for the institution.

One of the objectives was community outreach outside of Berlin?

Yes and no. Yes, we wanted to connect with our fan base. Up until 2008, the orchestra did not have any contact to the fan base. Except for a few thousand people who go to the hall every two weeks. As an artist, you were basically cut off. The [music] labels make the recordings of the concerts; you never get any feedback from any fans directly. So, yes, one aspect was outreach.

The other important aspect was that the distribution through labels and TV broadcast were doomed to die. Television stations had less and less slots for classical music. In the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, you had Saturday-evening classical music or opera or ballet. There were traditional slots on television every Sunday afternoon.

The labels were not willing to record the classical orchestral repertoire. They were gearing more and more towards soloist stars. The orchestra became a kind of companion.

We had to find a way to compensate, and we decided that the space where we were going to live was going to be the Internet.

The revenues from TV and physical CDs were just disappearing. That was an important part of a musician’s income.

How many of your supporters do you find are within Germany and how many reside outside the country?

About 25% of our viewers and customers come from Germany. Then there are two other important markets… Japan with about 20% and the U.S. with about 20%…where you have a lot of well-educated, culturally interested people. After that, you have countries like England, Spain, France, and Italy that make up 4-5% of our listeners.

Then… we have the emerging markets like Korea, Taiwan, and Brazil. In South America countries you have a completely different audience. You have the young people who learn classical music and are interested in European culture. They are longing to have this content available and accessible. It’s a different kind of audience, which we’ve never addressed before. At least, not as directly as we can do it now.

An interesting example is that the orchestra was—I think they were in Taiwan—playing a concert in 2005. The orchestra sits in a wonderful concert hall with a very interested audience, probably the higher-ranking people of the country.

After the concerts, the orchestra members went outside of the concert hall and suddenly saw that the concert was recorded by a camera and transmitted outside of the hall. There are 20,000-plus people sitting outside. Young people—interested and fascinated—a cheering crowd who just adored and loved the music.

That was kind of a turning point. [Sir] Simon [Rattle, artistic director] and the musicians said, “We have to do something; we don’t reach these people at all.” There is a potential and dedicated audience we have to address, somehow. The Internet seemed to be the only way to do that.

What did you learn out of all this?

I think the most important lesson is that the opportunities developed through the change of technology are always bigger than you can ever imagine. We never imagined when we started that, just one or two years later, every television set was suddenly Internet-enabled. We never imagined that social media would explode like it did. We never imagined that these iPhones suddenly were able to play high-resolution video and audio. We learned that it is wise never to underestimate what will happen.

Today, we sit here and we think, “Wow, three, four, or five years ahead, how do we imagine the future to be?” Imagine what will happen with virtual reality… and what will happen to 3D sound or high-resolution sound replication. You suddenly will have an immersive feeling of actually sitting in a concert hall. You will be able to decide, I want to go to Carnegie Hall, I want to go to the Royal Opera House or I want to go to the Berliner Philharmonic, and say, “I would like to sit in block A.” You put on your glasses and your headphones and you have the feeling that you are there. We still have a lot of interesting technological developments in front of us.

Are you preparing for this?

We are very much preparing for this. We’re cooperating with research institutes. We are doing trials and tests, together with Google or with Fraunhofer Society [German research organization with 67 institutes spread throughout Germany]. Or with other big companies, think tanks, who are going along the same lines.

We are a very nice guinea pig, because we have a good name, we have a very strong brand, and we have a venue that is great for such a purpose.

How do you see the concert experience in the future, apart from the virtual-reality part?

Well, the concert experience itself, as a physical experience, will never be replaced by anything. I’m quite sure about that. The big thing is going to be virtual reality. The other factor is sound replication. Today we are used to hearing stereo sound, either with two speakers or headphones. In the cinema, you may even be used to hearing surround sound.

There will be ways that you can replicate sound fields, just with two speakers. You will suddenly hear sound behind you. Or you put on headphones and you turn your head and the sound field reacts.

There are developments happening at the moment … that would enhance any digital-concert experience. Other things on the horizon are the end-consumer devices. Today, our aim is to be present in the living room. We are very successful in doing this, because we have digital-concert-hall apps on all the televisions. You have the apps on the mobile device that are now very easily connected to your home entertainment system.

At the same time, we are present when you’re on the road, mobile. Enjoying a concert when you’re sitting in the subway or when you’re sitting on an airplane is where we are aiming to be.

What can smaller orchestras do? You’re well funded; there’s capacity here.

There are two aspects to this.

You have to first decide: Is it a marketing tool to attract new audience to come to the concert hall, or is it a commercial activity with which I would like to earn money, as a musician, as an orchestra?

Many orchestras are starting to stream their concerts on their website and say, “This is us, you can watch it for free here. If you like it, maybe you can come to the concert.” It is a viable strategy and it has its justifications. On the other hand, I feel that if you give artistic work away for free, it loses its value.

Our strategy, right from day one, we wanted to create a business case, which generates income for the artist.

A good example is Detroit. Their concert hall is struggling for survival. The right strategy probably is, yes, we are going to do streaming to get our audience back into the hall.

You don’t have to tell anybody in the world to go to the Vienna Philharmonic. That would be a completely wrong strategy for them. Everybody has to find his own way. There are certainly brands in the world that have the power to be so attractive that people pay for valuable online content.

Other orchestras and brands and cultural institutions maybe can do a mix. They can say, “We have a part which is outreach. And another part with special things where we charge money to recoup a bit of what we are investing.”

We always ask people who their impact maker is. Who has left a professional imprint on your DNA?

In the end, probably my deceased partner and companion, Oliver Hermann, who brought me close to classical music and gave me the stamina and daringness to start something crazy like this.

A good example of this is probably: we’ve been preaching that the future is digital and online and that the CD and media industry is dying. But having said that, two years ago, we started our own physical label with recordings of the orchestra—because the orchestra wants and needs to be a recording orchestra. That’s in the DNA of the orchestra. They have to record their core repertoire. Even if they have recorded it 50 times before. The conductor, soloist, and orchestra have to record.

So we said, “We have to establish our own recording label, but we do it in a completely different way than all the others.” The packaging doesn’t look like a standard CD. It doesn’t only contain the CD, but also everything around the concert experience—in this one physical package. You get the videos, documentaries, and download codes.

The Berliner Philharmoniker CD Box with Sir Simon Rattle. All nine Symphonies of Beethoven. Photo: impactmania.

Retail doesn’t know what to do with us. Critics say, “Well, this is a lavishly wonderful packaging, but I can’t do anything with it, because it doesn’t fit into my usual CD shelf.” In the end, that was the point. You have to break common expectations and make something new.

By doing this, we also got out of the usual pricing mechanisms. Usually you say, that’s an in-consumer price: 30% remains with the retail; 30% remains with the distribution; the labor gets so and so much; and the artist, if he’s lucky, gets 5% of the revenue. By creating this big online community, we were suddenly in a position to address our fans directly and say, “Look what we’ve made: It’s craftsmanship, it’s special.”

That’s only possible because the orchestra is managing itself. They love trying out new things. They love being experimental. They love going new ways. They don’t care about industry standards. That’s not their world. Their world’s the creative world.

Give me one word that describes your journey so far.

Adventurous.

Robert Zimmermann, is the Managing Director of Berlin Phil Media GmbH. Previously, Zimmermann worked on a wide variety of projects for prestigious clients, such as Lufthansa, the World Bank Group, and various international banks. He also held several positions as restructuring manager and was managing partner of eins54 Film GmbH.