For the new impactmania and University of California, Santa Barbara program: Human Mind and Migration (HMM), we are featuring migrants who have been contributing cultural, social, and economic wealth and health to their adopted countries. In the series Americans, we are following a family’s migration journey.

Add your migration story to the HMM program: www.hmm.ucsb.edu.

Ernan Roman is the President of ERDM Corp. Ernan was inducted into the DMA Marketing Hall of Fame. He has been named as one of the Top 40 Digital Luminaries (Online Marketing Institute) and one of the 100 Most Influential People in Business Marketing (Crain’s BtoB Magazine).

impactmania speaks with Ernan Roman about his immigration roots that spurred him to establish the Taking Action political action group. Ernan speaks passionately about engaging the community to become better educated about key issues and to initiate actions that will support progressive causes and leaders.

Thought leaders who have spoken at Taking Action meetings include; William J. Arnone, CEO of the National Academy of Social Insurance; Hon. George A. Grasso, Supervising Judge at Criminal Court of the City of New York; Walter Mugdan, Acting Deputy Regional Administrator of the EPA; plus representatives from groups including Planned Parenthood; The Central American Refugee Center, and Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America.

BY PAKSY PLACKIS-CHENG AND NATALIE GOMEZ

How has your migration story aided in how you drive societal impact?

I am proud that our Taking Action group has registered many hundreds of students to vote. We have worked with the non-partisan League of Women Voters and the Board of Education to register voters.

It is one example of partnering with different groups to amplify what we can do and make a tangible difference.

Neighborhood grassroots activism’s strength is engaging with other human beings and finding something where you can make a difference. This is what I—one immigrant has done, which is representative of what many other hundreds of similar neighborhood initiatives have done.

You were seven years old when you immigrated into this country. Can you tell me a little bit about that?

It was horrible, it was heartbreaking—it was the most wrenching thing that I had experienced up to that age. It uprooted me from people who raised me. I lived in a culture where you had to be raised as a Catholic. As a Jew, I had to live sort of this other life.

The Catholic school priests must have known something was odd, ‘cause I was beaten regularly. I still have these images of these tall, black-robed priests taking off their belts and whipping me. I don’t think I was a particularly terrible person, but boy, it seemed to be disproportionately often that I was whipped, punished, or put in a dark closet.

They must have known that I was not necessarily a good little Catholic boy, that there was something else going on in my background. As tough as that was, of course, pales to anything that’s happening to people who are now coming from Iraq, Syria, Guatemala, and El Salvador.

Notwithstanding, it was quite horrendous, tough, difficult, and painful to be uprooted and suddenly thrown into New York City. Learning a new language and a new culture. My first time in Manhattan, I looked at these incredibly tall buildings, which my brain could not fathom—coming from Quito, which had only two or three-story buildings.

Or, walking with my grandmother, suddenly seeing a television set for the first time. She left Hungary fighting the Russians and throwing Molotov cocktails at the tanks. She became the incredible love of my life. We would walk the Manhattan streets and take me to Rockefeller Center. We would look at the windows and I saw this thing called a television, which was so remarkable.

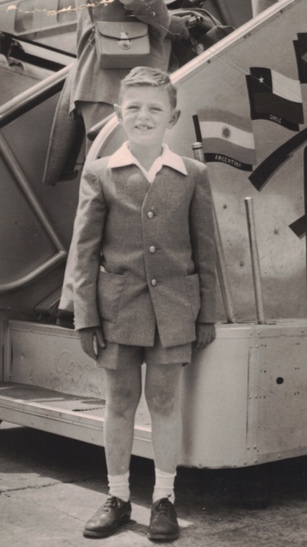

Ernan Roman (7) immigrated to the U.S. from Ecuador. Ernan Roman, “I am about to board the propeller plane by myself, for the long flight from Quito to JFK.”

How do you look at the immigrant issues today?

My heart particularly pains for immigrants. The abuse that I encountered from children. After I learned to speak English, I of course, had a “funny” accent. Plus my short pants—nobody wore shorts at school.

I was very small for my size and my age. Before I knew it, I was constantly in fist fights. I was getting beat up all the time. On my way home from school, there would be a fistfight. In the school bus, there would be a fistfight. Trying to go out and play with the neighborhood kids would result in some sort of altercation, because I was different. So, this puny kid from Ecuador learned how to fight. The number of bloody noses that I caused were necessary to work my way up the hierarchy.

There are immigrants coming to this country burdened by the baggage of the horrors of what they’re fleeing. What is it like for them to encounter the hostility that is innate to many portions of this country? Certainly with the current political tone or climate of intolerance. Even the lack of understanding of well-intentioned people who have not dealt with migration or integration can be painful.

Give me an example of how immigrating as a young boy, not being accepted stays with you. How does that experience impact who you are today or how you operate?

I think number one would be compassion. When I see someone on the sidewalk, I stop to talk with them, or give them money or buy them a coffee. That’s another way of saying thank you to the gifts that I received as I ultimately became more accepted in this country.

For years of my life I traveled and lived in Europe and in Mexico on a motorcycle. I didn’t have enough fuel for my bike and food for myself. The farmers who took me in in Greece, Italy, Scotland, Ireland, Israel, and Mexico let me sleep in their barn or took me into their home, fed me whatever things they might have. There is a cosmic debt that I owe.

That led me to creating the Taking Action group in order to try to do good things. It is about teaching my children these values. My wife, son, his wife, and our daughter are an incredibly tight-knit group.

Ernan Roman with his Grandmother Valerie Cseko and mother Eva Haller not long after his Grandmother immigrated to America from Hungary (1959).

When reading the interview about your mother, Eva Haller, what are some of the thoughts that go through your mind? Is the experience how she shared it with you? Or is her perceived experience different from what you know about her story?

It is exactly what I have heard and what I recall of the story. As I’ve heard the story at different points in my life of the difficulties and rigor, the challenge, required to cope with the unimaginable things that went on in Hungary. And surviving that nightmare and that horror.

Then having to do it again in a different way in Ecuador. Then having to do it again in a different way in America—three different major chapters of immigration, dislocation, adjustment, and assimilation.

I look at the media and hear the stories we tell each other. What do you do to get a balanced view of what really is going on in our country or around the world?

One thing that I hold most precious about being in America is the privilege of voting. And to vote, coming from a country where you had military juntas, that was the way power changed.

Armies and generals and bloodshed, not only in Ecuador, but throughout South America. I’m now 69 years old. So 61 years later, I go to voting booths, for a local election, for a national, for a primary, and for a congressional. There is not a time that I go and not get shivers at the privilege and the honor and the unique ability to make my one voice—my one vote—count.

I hold this so remarkably, fiercely proud that in our country, notwithstanding its many warts, its many ups and downs, that we can still vote. It is such a remarkable thing as an immigrant, to be able to have an impact on this country.

I tell my kids: “My God, you cannot miss an election!” No matter what business travel, where you’re living, where you’re going, get an absentee ballot. There is no acceptable reason to miss voting. It is unconscionable to be one of those people that say, “I don’t want to vote because my vote doesn’t count.” It is an absolute betrayal of responsibility and citizenship.

It’s an abdication of our responsibilities as citizens if we don’t vote, if we don’t do homework, and if we don’t do research.

Do you have any suggestions of what people should do, because with voting comes informed decision-making. Do you have any advice for people on how to go about making informed decisions?

My number one recommendation is: do not take the lazy or the easy way out, i.e. only rely on social media for news. That is not education.

Do the hard work of watching, reading multiple news sources, so that you balance your point of view. If you’re a liberal, force yourself to watch Fox News every now and then as much as you can stomach it. Make sure that you’re not just on MSNBC.

Because we are arrogantly narcissistic and U.S. centric—God forbid there should be anything about the rest of the planet in the evening news cycle. It is imperative to look at an international outlet, such as BBC, which is trying to give us a worldview. All of the news outlets have flaws, biases, but look at the aggregate stories, and then do your own thinking.

Number two, get involved with subject matter experts—join a group. That’s one of the reasons I designed our Taking Action group. We’re not all going to become experts on social security, but if I can bring in one of the economists to talk to us about what really is happening with the medical insurance plans, social security system, with the judicial system. What is really happening in science and climate.

Attend talks to learn. Those are the multiplicity of channels that I use to get a level of knowledge, or competency, and in the range of topics that we need to.

Going back to your own path, you came here when you were seven years old. What helped you integrate or helped you forge your own life here, your own identity. What needed to happen?

One of the great gifts that Eva gave me—while we did not have money—she prioritized education, and got me into the United Nations School. The United Nations School had children of diplomats with a similar background. They grew up in other countries, suddenly came here and couldn’t speak kindergarten English.

Well, we were all in that boat. We were all foreigners. We all had funny customs and we all dressed funny. We were all learning English, which was a bit odd given our age. That was incredibly helpful.

The other important gift that Eva gave me was pulling me out of a local redneck high school, and send me to a Quaker boarding school. There I could be with people where we could have shared values. I could learn and it wasn’t about a fistfight between classes. I could be with people raised to be thoughtful and raised to ask questions, raised to be polite, and inquisitive, and intellectual.

I’m sure throughout all these phases, you must have felt a changed identity. Can you give me an example of the person you’ve become through this very specific immigration story?

I am proud to be an American, profoundly so. My love of this country, for what it has to offer, the opportunities it provides multitudes of people is profound.

I enjoy driving fast cars and motorcycles, and racing automobiles. And absolutely, I will buy American-made automobiles. It’s a statement of pride in America. I will only drive an American regular car or an American performance car like a Corvette.

I feel strongly about supporting America. For example, Taking Action, doing what I can to help steer America back onto the track that it has to get back onto. It has dangerously deviated from in recent years.

For somebody who is not a flag waver, I have a small American flag in our front lawn! When I decided in the last few years to get an American flag, I was quite struck at myself, that I would do something like that, given my resistance and counter-culture background. I look at myself and said, you have a goddamn American flag. What the hell’s that about?

It’s okay to love your country.

Yeah, exactly, have a flag as long as you are not blind to the flaws of your country. It blows your mind that some think people are fleeing Guatemala and El Salvador to get free food stamps! Is that really why they’re coming here? You don’t think that they are migrating because of raping and killings?

For those of us who love this country and who come from an immigration path, we must do more to be welcoming.

Photo: (left) Ernan Roman with wife Sheri and daughter Helaina. On the right, Ernan’s son Elias with his wife Sarah and children Ethan and Holden.

How has your immigration story affected your children?

Immigration and doing good for others is a core value in how my wife Sheri and I have raised our children. It is a major narrative of my life. My political activism is a major point of family conversation.

Our kids are politically active, and the narrative of immigration is a defining element of my life which is very real and has been in their upbringing.

My daughter, Helaina, will stop to speak with homeless people on the street and give money. Or, she will go to the store and even though sometimes this is on a risky and dark street, she buys food and sits with people who are on the street while they have the meal she brought them.

She is also an ardent feminist. For years, she has been involved with mentoring young women or disadvantaged kids in various neighborhoods.

During a recent birthday celebration for my son, Elias, his wife, Sarah, gave him an envelope. As soon as she handed it to him, a huge grin appeared on our son’s face. He is one of the least materialistic and most humble people I know.

Elias leaned over, kissed Sarah, and opened up the envelope. There were 100 one dollar bills that she had given him as a birthday present so he would have an ample supply of singles to hand out to people on the sidewalks of New York.

To have passed along this sensitivity is very gratifying. Passing along to your children, the lessons you’ve learned, is a major obligation we have as parents, particularly those of us as immigrants who had the worst and the best of it too.

Is there anything specific that Eva [Haller, Ernan Roman’s mother] has said while you were growing up that has stayed with you?

She made me realize that I could’ve been one of the Jews taken by the river, had my shoes removed and then lined up and shot in Hungary. I could have been one of the ones that came to this country, not make it, not adjusted, and fallen into a life ruined by drugs or poverty.

The knowledge that in this country many—though not enough—can win! Many have the opportunity to grab life and forge success! This in contrast with those poor souls who are basically screwed from birth because they do not even have the chance to win.

My heart breaks for those children in particular. Whether it’s a minority in our country, or whether it’s the immigrants. That has stayed with me profoundly. My story would have turned out so differently, were it not for a chance to make it. And therefore, the humility that that has taught me; that whatever I think I’ve accomplished, it could just as easily have been different.

You’ve been a young child, separated from your mother. Thankfully, you had other family members caring for you, do you have any advice for parents who’ve been separated from their children? We see a lot of migrant workers in the world who are separated from their children for decades, right? Any thoughts on how parents can help their children emotionally?

Wow. That’s a huge question. There is no way that a parent can comprehend the disruption, the damage, the hurt, and the betrayal. The cosmic uncertainty separation from your parents can cause.

The amount of love, nurturing, consistency, and presence that the parent must provide is enormous and unending because of the depth of the wound and upheaval that occur. I’m ill equipped to offer advice, because I can’t even comprehend what those children of immigrants separated from their parents have to endure. What I went through is a picnic compared to the horror of what it does to a child to have the parent ripped from them at a border crossing. How do they recover? How does the kid get over the anger?

How as a parent—with your own anger, hurt, and guilt that you suffer—do you deal with that? Just give children the love, the guidance, the unrelenting presence and support, and unconditionally so. I feel so ill equipped to comment much more on that because I truly do not have a sense of the enormity of that.

What are some specific things that have helped you in healing that breakage in bond?

Trying to understand my mother’s journey. Trying to understand what she went through and the toll and price that was inflicted on her as a young person. There will always be that level of damage and needing to try to understand it. The pervasive insecurity, uncertainty, anger, furtiveness.

What are a few words that describe your journey?

Use the skills and the obligation to become good human beings to cultivate compassion and understanding, notwithstanding our personal challenges. Try to be as generous as we can with our fellow beings.

I cannot imagine people not agreeing with that statement. How is it, maybe, we help others who experience pressures on their own families? How do we start a dialogue with people who act out of fear? Who will take your comment and say yes, that’s easy for you to say, my job is gone—my family faces hardship too.

An important starting point to the conversation is that there is so much to go around in America. Somebody else’s ability to gain does not take away from you.

America is not a zero-sum game. My gain is not your loss. Your loss is actually my loss because I care that you don’t have what you are actually entitled to and deserve. Don’t operate in a scarcity mindset because that makes you adversarial, and that shuts you down, as opposed to opening up to the opportunities that can help you emotionally and psychologically do better.

If you’re cowering and scrounging for the acorns because there are so few, then you’re not going to see the forest. Not being controlled by scarcity is very important.

Number two—what are the avenues of support that can help you actualize what you want to do and be? You can always find a job. You can always find an afterschool or an enrichment program. It is an obligation that you not give up. You have to, however, be creative enough to find a solution.

In every country, especially America, do we really have to shut down the social services, resources, and programs? Taking away kids’ free lunches? How can we not find the kindness to fund $1.50 for a school lunch.

That’s the scarcity model that says, I’m paying for their lunch and I’m tired of paying for these people. It makes the job of changing that much harder but we’ve got to shift out of the scarcity model because it brings out the worst in us.

I still want a few words that describe your personal journey.

[Laughs.] Lucky son of a bitch, how’s that? I got to do a lot with what I had.

Human Mind and Migration is an impactmania program in partnership with the Neuroscience Research Institute, Department of Religious Studies, and the Art, Design & Architecture Museum at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB).

Add your migration story to the HMM program: www.hmm.ucsb.edu.