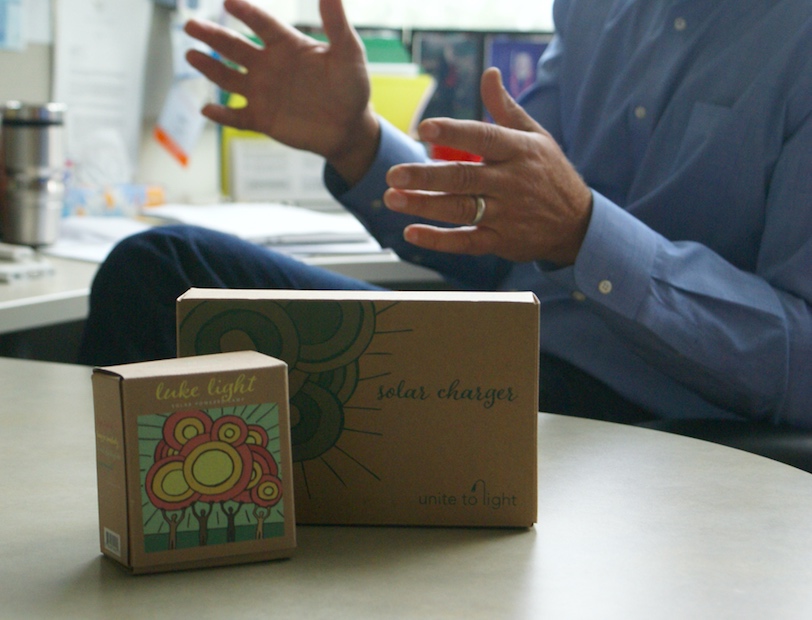

John Bowers, founder and Megan Birney, president Unite to Light

While we are sitting with our lights and screens on until the wee hours, school children in countries such as Ghana are using open-flame kerosene lamps to study. Four hours of their lights emits fumes equal to smoking two packs of cigarettes.

Visiting Professor Osei Darkwa from Ghana asked Professor John Bowers, Fred Kavli Chair in Nanotechnology, what good UCSB was doing for the world. Darkwa could not have asked a better person. Bowers, who also serves as the Director of the Institute for Energy Efficiency (IEE), called a team together to build a better solar light: which spun out of IEE to become the nonprofit Unite to Light. Megan Birney, Unite to Light’s President, joined Bowers and the original team spreading solar reading lights from Accra, Ghana, Dhaka, Bangladesh, and back to Santa Barbara, California.

BY PAKSY PLACKIS-CHENG

I am fascinated by how research ends up being offerings out in the marketplace. How can we help university students and faculty drive more solutions into the world?

John:

It is partially by getting the story out. Let people hear about the success stories, get inspired and join in.

Universities don’t exist just to do academic research and write papers, we can positively influence the community. I come from Stanford [University], and Stanford is well known for the impact it had on the Bay Area.

It’s probably been too successful, but they’ve made a huge impact. The same thing with MIT, they have made their communities better, and provided high paying jobs for lots of people. UC Santa Barbara can provide the same value and expand our jobs beyond the tourist industry. What we’d like to get is higher paying, quality jobs for the community. That’s is part of our responsibility.

What we should do is train people to be successful in business and come up with good ideas that can get out there. There are lots of problems in the world. The incandescent light bulb, for example, has a glass envelope, metal and wire wound things. This is now a stupid way to make a light and it’s takes a lot of Earth’s resources and wastes energy. With LEDs, you take a wafer and you get 10,000 LEDs on it that are 20 times more efficient. That’s a great example of what Shuji Nakamura [Nobel Laureate in Physics] has done for the world. All of us, throughout the world, we need to keep the world marching forward and solving problems, and making the world more energy efficient.

How is Unite to Light aiding the one billion people who don’t have light?

John:

One billion people don’t have solar lighting. If you add the term, reliable, it’s about two billion. Technologists have a responsibility to change the world so that people in Africa are not burning kerosene. What they should have is some renewable light source, like a solar panel, and some sort of efficient light bulb. Right now the most efficient light source is an LED. With these solutions, people don’t breathe fumes; we don’t put CO2 in the atmosphere. They don’t spend more money on buying expensive kerosene every day.

In an earlier interview, you mentioned Osei Darkwa, a professor from Ghana, who spoke to you about the needs in his community that led you to develop a new light.

John:

Yes, Osei Darkwa, who ran the Telecom university in Accra, the capital of Ghana, had come to see the Dean of Engineering about his mission to get electricity to everyone in Ghana.

Osei said that only 25% of the people in Ghana have electricity. And it’s only the people in the south and right along the coast. About 75% of the people in Ghana, especially in the north, don’t have electricity. Students who grow up without electricity don’t have the skills they need and often don’t graduate.

Osei comes into my office, sits down, and I started explaining about all the work that Shuji Nakamura [Nobel Laureate in Physics] and the group is doing on LED lighting. I mentioned the work of Alan Heeger [Nobel Laureate in Chemistry] on solar cells and battery research. Then Osei says—I remember this very vividly—his exact statement was, “Why don’t you do something good for the world?”

[Laughs]

“It is really cool and it is important stuff you are doing,” he says, “but it’s not impacting me at all.” No one in Ghana can afford a solar powered LED light. At the time, they were selling for $30 each, and he continued, “Thirty dollars is more than a person’s annual salary.”

I didn’t really want to get involved. I sent him an email with eight different places that made solar lights. They did all cost more than $30, which unfortunately verified what Darkwa said.

We get to hear about challenges of the world on a daily basis. What had to happen to turn a comment from a visiting professor into an actual solution?

John:

We had to figure out how we would make something a lot cheaper, but as good or better than what was out there. One of the designs had nine LEDs. It had three AA batteries in it, and that was necessary ‘cause you need 4.5 volts. It was an intelligent design but you could do a lot better. One high-powered LED will put out enough light; you don’t need nine LEDs. We designed a system with a voltage tripler inside of it. Now from one battery, you could get 4.5 volts. That cut the cost down by a factor of three and we gained probably a factor of at least ten in the LEDs. Not buying multiple LEDs meant you didn’t have to assemble them in this package. Most LEDs that you buy have large arrays of them and our approach was just one higher-powered design. Then the third thing was we resized the solar panels, it was a little smaller and a little higher efficiency than what they were using. They were using polycrystalline solar cells, and needed a larger area. We went to higher efficiency monocrystalline solar cell. Because it’s higher efficiency, it could be smaller.

Were students or outside companies involved in creating the light?

John:

We originally got involved with Engineers Without Borders. They went out and bought a whole bunch of lights and tested every light on the market. The problem was that everybody had a different idea about what to build; there was no focus in the group.

So, I gathered a few engineers in the area. David Schmidt, from Calient Networks, a company I had started, did the electronics. He had the idea, OK, we don’t need three batteries, we can do this with a tripler and it’ll cost $0.15, it’s a simple circuit.

Norm Gardner did the physical design; he made the original Unite to Light. We went down to Ventura and had the 3D printing of the original case. We made five up and we sent them to Osei Darkwa. Then Pastor Kofi Fosuhene got involved; he was part of the group who brought Osei Darkwa here. After the five lights, we made a pre-production run of 30 lights.

Goleta Presbyterian Church sent a group to Ghana with the lights. They also asked everyone for feedback, “Does this work, not work?” One of the women connected with the Goleta Presbyterian Church was driving down the street, early morning, and she saw this light and pulled over. It was our Unite to Light. The light came from a bakery. They were doing all the preparations via our Unite to Light. She wrote back and said, “Yes, it seems to be working—and the people seem to be using it for many other things than just studying!”

We added a number of production runs and [investor and philanthropist] George Holbrook, who has been on the board stepped up. It was costing us $7 just to 3D manufacture the parts. We had to get the total cost down to $6. He paid for an injection mold and the first production run. We made 1,000 lights and then we used the mold for another six, seven years, until pretty recently.

We recently hit the 100,000 light mark.

You mentioned in a previous interview that you want a million lights out there. How are you going to get to the million?

John:

We need distribution sites in Africa. When you ship smaller quantities by airplane, that’s expensive. We need to be shipping a container full of lights to Nairobi and other places, and then distribute from there. Rotary has been a great partner in terms of getting lights out. Direct Relief has also been a great partner in getting the lights out, particularly for midwives and disaster relief.

We need entrepreneurs in Africa to sell our lights. We also have a Solar Charger with a light, a larger solar panel, and USB ports to recharge a cell phone, which is a big need.

In Africa, they don’t have landlines and many people have cell phones, but don’t have electricity. We’ve continually received feedback that lights are good, but a cell phone charger is needed. You shouldn’t have to pay $1 to have some person with a diesel generator to charge people’s cell phones.

There are many similar lights out there, right? There is a similar organization in the Bay Area that distributes solar lights in Africa. Apart from price, what is unique about Unite to Light?

Megan:

We’re in 70 different countries. Even the U.S. has people without electricity. We are trying to dispel the notion that all of the people we’re trying to help are in Africa.

Bangladesh is a huge place that we’ve worked in the last year, Peru, Puerto Rico, which is a U.S. territory. It started in Africa, but that’s not necessarily our only focus. It’s really anyone without access to electricity.

SolarAid and d.light, are for-profit business. In addition, they donate some lights, which is amazing. We’re unique in that we’re solely a nonprofit, and that gives us a lot of standing with our nonprofit partners. One of our biggest sales channels is through other nonprofits.

You give one light for one purchased. A model similar to TOMS shoes, a company that received criticism of undermining local markets. Free is always better than paying. How can local merchants do business when you compete against free, because now we’re going and handing out free backpacks, free shoes, free lights. What is your thought on that?

Megan:

We’ve been really careful about who we give these away to versus who we sell them to. We’re giving them away to people who really can’t afford even the low cost of light.

We have three focus areas: education, global health, and disaster response. In education, it is a student who can’t afford a light. In global health, we’ve partnered with midwife programs in Bangladesh. We would rather the midwives and the hospitals spend their money on gauze, on sutures, on those types of things, not on a solar light. It is the same thing with a disaster, right? Somebody has lost everything they have.

Then we are starting with resale. We’re working in Zimbabwe with Alight Zimbabwe Trust, and in Haiti with Fonkoze. These groups have entrepreneurial programs that are selling products in those countries.

We sell lights to them at a discount. Then they’ll go out and sell to those in their community who could otherwise use them. So we’re doing economic development in those communities. It goes back to our mission and what we’re trying to do. The new light charger is great, it’ll charge your cellphone and it works for a lot of small medical devices.

What’s next?

John:

Scaling!

Megan:

To make the next one waterproof! [Laughs]

Right now it’s water resistant. Some of the places we work, like Haiti, there’s a lot of moisture. If there is a storm, if we are working in a disaster area, we just want it to be as best as it can possibly can be.

We have three kinds of business models. One is a traditional nonprofit: we apply for grants, we do fundraising events, we ask for donations, and we donate lights to our partners in those three areas.

We sell them through nonprofits such as the Rotary. They will often come in, and say, “We’re going to do a project in Mexico.” They’ll buy a hundred of lights, hand carry them down to Mexico, and give them away as part of their projects.

We also have partners like the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Last year, UNFPA came to us in Bangladesh and asked how many lights for the Rohingya refugee crisis they could get for a certain budget. I said, “Well, let me see what we can do.” We leveraged our network for additional donations and ended up giving them about 30% more lights than they would have been able to get.

Then, we do a TOMS Shoes model, for every one of these I sell to you, I charge you double, but then we give one away. That’s actually how we paid for the solar chargers our first round.

We did a presale in June, we sold 300 presale on a buy one give one basis. That gave us enough to make that deposit and get those chargers. Now, we’ve got several hundred to give away. We did that through strategic partners: Direct Relief, the Edna Adan Foundation in Somaliland, which is a teaching hospital and school, and Africa Schools of Kenya.

John Bowers, founder and Megan Birney, president Unite to Light. Photo by Nerwel Zhao, AD&A Museum (UCBS)/impactmania.

All together, from creating to distributing the light, it sounds like a coming together of powerhouses; most scrappy startups don’t have advisors and partners of this caliber.

John:

Exactly. I would say what it took was the people and the organization. We have such a strong group of caring individuals, and such an important group of people on the ground.

Megan:

We can really stay lean and keep our cost down by depending on our partners. We joined the UNFPA’s Safe Birth Even Here. This campaign is with Johnson & Johnson, GE, Phillips, Babybox, and Parson School of Design. We are trying to ensure that women have safe births, even in conflict zones, even in refugee camps. Last year through a mixture of donation and sale we sent 11,000 Luke Lights to the Bangladesh Midwifery Society and the Rohingya Refugee camps. The UNFPA was the catalyst for this project and ensured that the lights got to those who needed them the most.

Finding those partners is really what does it for our little organization.

What has been the biggest or most surprising learning, in building Unite to Light?

John:

Maybe, I’ll put it as a frustration, that is hasn’t gone faster, and there are still billions of people burning kerosene today. It’s cheaper to buy one of these lights than to burn kerosene, it pays for itself in three months max, and lasts for years, so why hasn’t this just taken off?

There’s a barrier; people are very willing to pay for a week’s worth of kerosene. But they’re not willing to buy a light, and so it hasn’t gone as fast as I’d like to see.

Is it distribution, the last mile into people homes, or what do you think is the issue?

Megan:

Yes, it is really infrastructure; we are starting to dip a toe in Zimbabwe and Haiti. Those will be good learning lessons for us. How do we do that without being in the country ourselves?

My biggest lesson learned is on the positive side. I came from solar advocacy and finance. I thought this would be more of a solar role, but it’s not, it’s a humanitarian aid role, to be perfectly honest. Solar is the technology, it’s the means to the end, but it’s humanitarian aid. Especially when you get frustrated, you look to your partners. There are so many people in the world trying to make a difference and trying to do good. That’s my favorite part of the job—who we get to work with. These amazing organizations and amazing individuals are doing work all over the world. It’s really lifts everybody up.

John:

There’s one more point we haven’t made that we need to which is, what’s really satisfying or gratifying, is the impact on education, which has been a lot of our focus since the beginning. Through Suzanne Cross, UCOP, [University of California, Office of the President] we’ve now got really good statistics in South Africa about the impact on graduation rates.

The graduation rates increase by pretty much 30% when you give students lights. Students are motivated to learn, they just need the tools.

Light is so important, even to improve safety on streets.

Megan:

It really is. We’ve heard that feedback from a lot of people that just having a light is enough. We’re also doing a project here in Santa Barbara [California] with Safe Parking Program, which gives people who are living in their cars a safe place to park at night.

The women are saying that having the light makes them feel so much safer and more secure. If somebody approaches their car at night they’ve got a light, being able to call for help.

Santa Barbara Gives, a program between the Santa Barbara Independent and the Fund for Santa Barbara, has selected 55 nonprofits. We will be participating and are raising funds to donate 350 chargers. We’d like to give all of their homeless veterans chargers so they can have a cellphone to connect to services.

The campaign runs from through December 31st 2018. For more information: Unite to Light.