Puk Damsgård in Mosul.

BY PAKSY PLACKIS-CHENG

Life in a War Zone

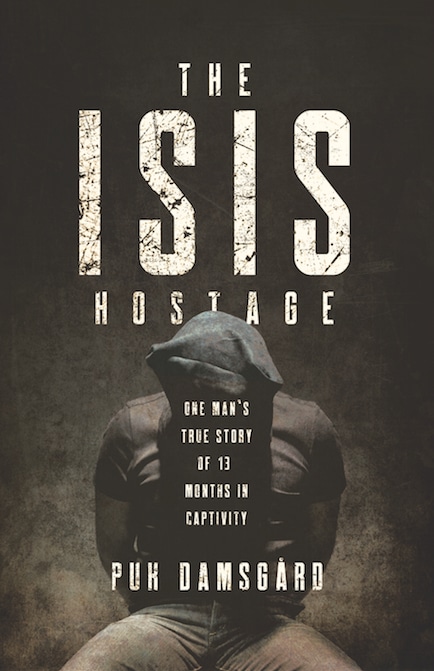

Puk Damsgård has been the Middle East correspondent for the Danish Broadcasting Corporation (DR) since 2011. She has been recognized for her work as a journalist and author, including having been awarded Denmark’s prestigious Cavling Prize. Her latest book The ISIS Hostage: One Man’s True Story of 13 Months in Captivity is about the photographer Daniel Rye Ottosen who was captured in Syria and held prisoner by Islamic State (IS) along with eighteen other hostages, including U.S. journalist James Foley.

Puk Damsgård speaks with impactmania about her life and work in the Middle East, what she learned writing the book The ISIS Hostage, and a misunderstanding the West has of the situation in Syria.

Puk, where is home?

Home is in Cairo, Egypt where I have lived the last three and a half years. I have also lived in Beirut, Lebanon; Kabul, Afghanistan; and Islamabad, Pakistan. I was born and raised in Denmark, which is also my home. But I feel at home anywhere in the Middle East.

Why do you feel home in the Middle East?

My life and work is here. It has been for the past nine years. I started working as a freelance journalist in Pakistan. Exploring a region that is culturally and politically different from the place I grew up in, fascinated me.

I wanted to discover and understand what’s happening in other cultures and try to build a bridge back to the Danish audience. If I can make one person more interested in the region than they were before, then I feel it has been an accomplishment.

What are some of the things you have learned by living in the Middle East?

You learn a lot about other people, their cultures, and how they work. But, you also learn about you own society, because you start seeing it through a different lens. That is healthy.

Then, there are just as many young people that dream about the same things as any Dane, European, or American would dream of. It is very difficult for people to follow their dreams due to the war and poverty. It’s important to report about this because what it tells us is that we’re not quite different from one another in the world. It depends on where you grew up, what you have been given, and what opportunities you had.

One thing I have learned is how strong and resilient people are in war zones. What they can make out of their lives despite very difficult situations. For example, people living in Mosul, Iraq are under the control of ISIS. Yet they live there, invite you in, and manage to cook some food or hang out in the garden.

Kids play outside, right?

Kids do play outside. Often they are also found in streets where they’re not supposed to be. The kids in war zones are the most uplifting to meet, because somehow they still manage to play. If you look at their parents, it is difficult for the adults to get beyond the fear and out of their depression.

The kids that fearlessly run around are unfortunately also often the victims. And of course, they are the victims in the long term, because when they grow up, this is what they carry with them.

You have made a life in the Middle East, witnessed history through your work as an author, journalist, and correspondent, what would some of the first steps be for social impact in the region?

The revolutions in 2011 were the beginning of recognizing that people have a voice. Many realized that by standing together and taking it to the streets helped remove the dictators who have suppressed people for decades.

It happened in Indonesia, Egypt, and Libya. It didn’t happen so well in Syria — people did not expect to still have President Assad in power. Unfortunately, it turned into a brutal, dirty, and bloody war with all of the world powers involved.

But what we saw during the Arab Spring was something that people had wanted to see for decades. Even though, situations in some of these countries, where we saw the revolutions, are still not the best.

In Egypt, President Sisi is elected but many people feel that progress have been rolled back.

Then of course change is not something that happens overnight. It takes many many years, similar to what we have seen with the climate change issue: How do we change our behavior to save the planet? It takes decades to change the way people look at politics, to have a development towards a better understanding.

Politics is also about compromises, even with your worst political enemy. We’re not getting any further by having one strong leader. People think that one strong leader who takes actions can change the situation. Many would argue it ends in chaos. I think change starts with people. They now know that by standing together they have power. That is definitely a first step.

What is a big misunderstanding that people have in the West of the situation in Syria?

One misunderstanding is that people believe that by fighting Islamic State, ISIS, in Syria will solve the Syrian war. ISIS in Syria is a symptom, a consequence of a much bigger issue, which revolves around Syria’s leader President Assad.

What people tend to forget is how the revolution and later the war started in Syria. In 2011, many peaceful civilians went to the street to call for reforms. They were met with brutal power. The regime didn’t want to meet and talk. They immediately called people terrorists. The problem in Syria is much deeper than ISIS. ISIS grew in Iraq and then expanded further in the chaos of Syria.

The West focuses on fighting ISIS because we see them as our enemy. Whereas we don’t feel threatened by President Assad. There’s never going to be peace in Syria unless you focus on the much broader issue. We have this one string approach dealing with Syria. It’s a very complex situation with so many powers involved now.

What has happened in Syria over the last five years is a disaster of our time. We have seen how the UN body has failed to meet the needs of civilians. It has failed to even pass the most simple resolutions because the veto power of Russia.

I do not like generalizing, but we should be careful not to look at the Middle East or Africa or other regions with only our own lenses. You can’t say, “If Egyptians want Democracy, it is Democracy our way, because that’s the only way.” I do believe that Egyptians want Democracy but view Democracy differently than we do. They want to have their own identity. It also happens when Arabs look at the West, they have certain ideas that may not always be true.

The more connections you can have between Europe and the Middle East, or America and the Middle East, the better understanding you create by having a platform where you can discuss and disagree.

What was the process like working with Daniel Rye Ottosen, writing your latest book The ISIS Hostage: One Man’s True Story of 13 Months in Captivity?

I sat with Daniel, his family, and all the other actors around his kidnapping by ISIS in Syria for many, many hours. The book was important for me to do because it was a story about many different things.

First of all, it is about one man’s and his family’s survival from a gruesome experience. How do you cope with being kidnapped for 13 months? How did a normal Danish family not particularly busy with the Syrian war, suddenly deals with the war that came to them, because their son is kidnapped?

Then it was also a chance to get insight into the machinery; who were the prison guards? How did they act? What did they tell the prisoners?

The interesting part is not the gruesome things that happened to the hostages. We all know that once you are a hostage, it is not a fun picnic. We know the brutality of ISIS, but who are these people? When they spoke to the hostages, it wasn’t so much about religion, it was about politics.

The hostage takers were busy with politics and the lack of opportunities. Abandonment and isolation in the country you grow up in leads to extremism. Suddenly there is a battlefield where people from all over the world are invited to join in; being part of ISIS is being part of a new identity.

I captured many details and reconstructed the story of what happened in captivity for Daniel and the others. The book also shows the hostage negotiations and how Daniel managed to get out. We follow the security guy who worked on getting Daniel and James Foley out. He lost one battle [James Foley was beheaded] and won one [Daniel Rye Ottosen’s return to Denmark].

Puk Damsgård’s book, The ISIS Hostage, will be out in spring in the United States.

You never reflect on how dangerous your job is even after speaking with Daniel?

I reflect on it all the time because a dead reporter is not really worth anything. [Laughs.] For my book about the Syrian war, I traveled a lot through Syria.

We prepare ourselves by how we travel, whom we travel with, and questioning the dangers. Of course, there are many factors that we can’t control. We can’t control where the bombs are going to be and whom we’re going to run into in these war zones.

It is a part of the job that is necessary. It’s important for me to go and hear what people are saying and find out how it is to live in these war zones.

The sad thing is, I can leave when I want, while people who live there can’t. These people are in great danger every day.

That’s something one should remember, the security issues are something we deal with behind the story. It should not be a story in itself. I’m a firm believer that the journalist is not the interesting person, but the people we talk to.

What spurred all of this, Puk? I’m sure you could have done so many other things. What made you felt compelled to go to the front line, report on the situation, and hoping to build a bridge back to the West?

It is experiencing life, not necessarily at the very front line, but in a difficult environment.

Because when life and death are so closely connected — one moment you are alive and next, if you go to the bakery you might die. In a way, there’s so much life, good mood, humor, and survival despite the situation.

I enjoy seeing that some guy in Mosul just opened a tiny little restaurant under a roof that has half fallen apart. Daniel [Rye Ottosen] said somebody found a football. They end up playing football with an audience on a roof that was falling apart.

These things motivate you to go there. I have a special heart for the Middle East and that’s because I have lived here for almost six years; you become a part of the community.

Then, journalistically, I’m fascinated to go and experience and write things that I never would have thought existed.

It’s important that we are curious about the world. It’s important that we allow ourselves to be surprised by the world, and not just sit back and say, “It must be like this and that.”

We always ask interviewees who has had an imprint on their professional DNA. Who has made that impact of you becoming a journalist and how you operate?

I have to mention my mom and dad. I grew up in the countryside in tiny Denmark in a lovely cozy home in the countryside with deer in the garden. [Laughs.] I am an only child and got all the attention. My mom and dad are not very worldly. They were quite shocked when I, as a 14-year-old, said, “I want to go with my girlfriend from school to visit her dad in Kenya this Christmas.”

Until then, my holidays had only been with where we can take the car. My dad would always want to take the car, and not fly. They said, “Okay, you can save up money for the ticket.” They’ve always said that whatever makes you happy, you should do.

Even though they might not understand what I’m doing in the Middle East. I don’t think my dad especially understands it. [Laughs.] But he appreciates what I do makes me happy and they have always supported me. That’s important, because if your childhood home is quite set in ways, it can be difficult to go another direction.

My parents gave me a firm foundation. Because when I fly away and have to go into all these difficult areas, I am mentally strong. I don’t have my job because I am fleeing from something. It’s important to be mentally healthy in this work, because if you see two dead children on the street; what are you going to report back home?

Puk Damsgård in Iran. Photo by Mathias Vejen.

What have you learned about yourself doing this work?

I have always been very conflict shy. [Laughs.] I would never mention something that bothers me. Now, in the Middle East, I keep standing in offices dealing with bureaucracy.

I also learned to manage my patience, being restless doesn’t always work here. Sometimes you need to drink many cups of tea and coffee, and are offered many cookies and lunches before something happens. [Laughs.] I have learned to appreciate that. Even war has its busy times and times where you just need to relax.

Through this work, you also meet a lot of interesting people. I’ve recently met a young woman from Texas who is working in northern Iraq as a tattoo artist. She’s tattooing all these big American guys with their girlfriends’ names. She’s become quite famous, may be the only female tattoo artist in Iraq!

She set up shop there?

[Laughs.] Yes, in a field in northern Iraq. Yeah, 50 minutes drive from Mosul.

I guess that needs to be done too, right?

Exactly, that’s how life goes on.

Give a few words that describe your journey so far.

It’s beautiful and it’s very difficult. At times it is black and dark, but there’s always a light. We would not see the light if we didn’t have the darkness also. I do hope that we are learning from what’s going on in the Middle East.

The world community needs to be better in responding to this amount of killing and bloodshed. I’m not saying that it is easy. I don’t want to be clever in hindsight and say, “This could have been done.” There are no easy fixes.

We have to be aware that by watching and sitting, is also acting.

In a field hospital in Mosul, Omar, a father is holding his daughter. She was killed by a bomb. Photo by Mads Kongerskov.

When people watch the news, read this interview, what can they do?

Yeah, I totally understand when people ask, “What should we do?” You feel powerless. A wonderful starting point is when people take an interest. That they’re not turning a blind eye, even though they have seen the same over and over. It’s like, “My god, there is more ruin and more bloodshed.”

If they take an interest, they will form their own opinion. When people have opinions, they often raise their voices. Then as voters, they have an impact on our political leaders.

This is what I’m trying to do. I’m trying to convey what’s going on in the Middle East to the average Danes and others that read my book. By describing people’s lives, it brings humans closer together. Imagine your best friend lives in Damascus right now. You would automatically take more interest. Does she have electricity? Is she a refugee? Has she been killed?

Because there are not many friendships between people in the Middle East and Europe for example as there are between Europe and the United States, we have to build connections through media and books. When people can relate to someone in Damascus, they can also relate to the war.

Puk Damsgård’s book The ISIS Hostage: One Man’s True Story of 13 Months in Captivity is scheduled to release in the spring of 2017 in the United States.