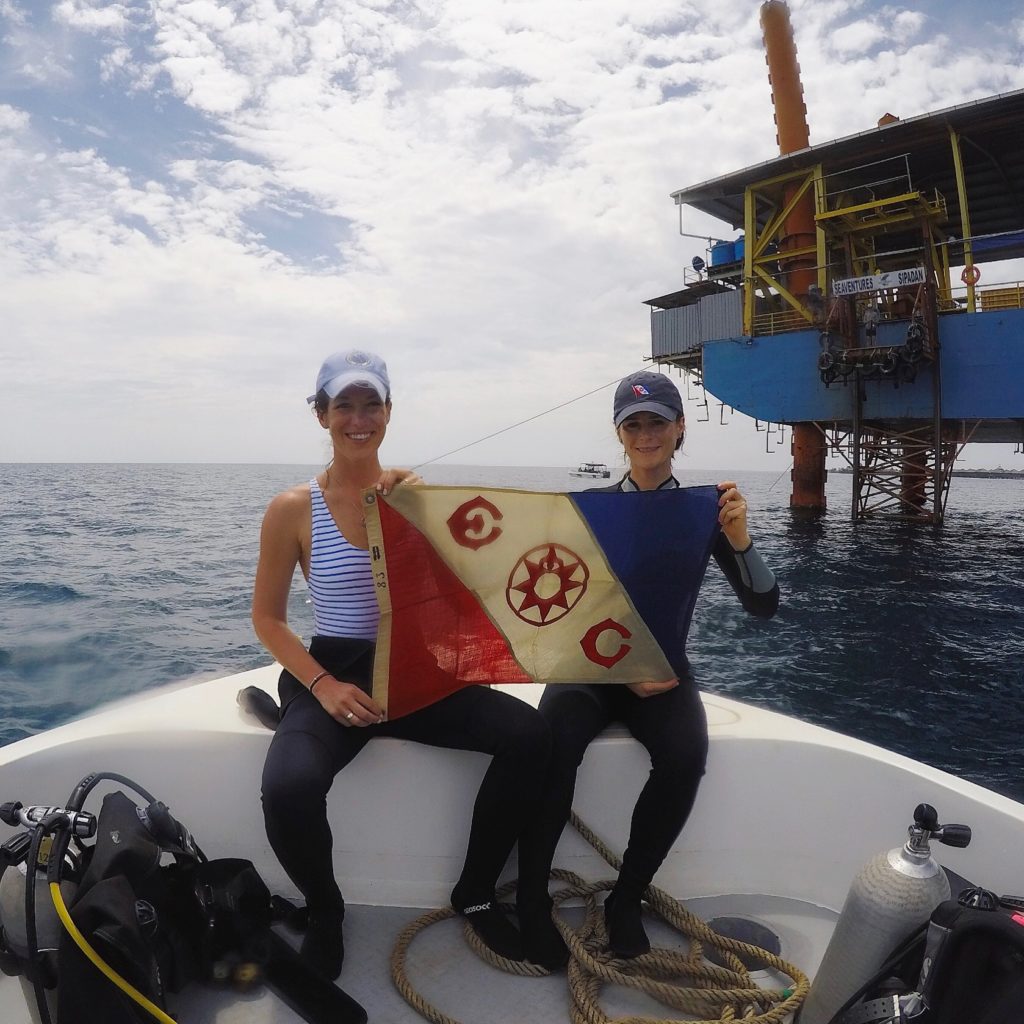

Emily Callahan and Amber Jackson, Founders of Blue Latitudes. Photo Courtesy: Blue Latitudes.

BY PAKSY PLACKIS-CHENG

Driving along the Californian coast, you will spot 29 oil and gas platforms, 16 of which are actively producing. The State of California recently announced that it would be decommissioning one of the first of these platforms off the Santa Barbara shore.

A complete rig removal is a complex undertaking. Platform removal is costly; leaves an enormous carbon footprint; and damages the marine life around the structures. The “Rigs to Reefs” (R2R) program (Assembly Bill 2503) offers oil and gas companies the possibility of a partial removal. The cost savings of removing the top part of the rig will be divided between oil company and funding conservation efforts. Most importantly it will support existing and future marine life.

Amber Jackson and Emily Callahan from Blue Latitudes have researched the Program extensively and are advising companies and governments globally. The founders of Blue Latitudes spoke about their work in the ocean; the partnership with oceanographer and explorer Sylvia Earle; and what oil platforms and wind turbines have in common.

The California coast is lined with 29 off shore oil and gas platforms. How many of these are already decommissioned where the upper part of the rig is removed?

Emily:

That would be zero.

What is the timeline for all of this?

Emily:

Actually, this Monday [April 24, 2017] it was announced that platform Holly, right off of Santa Barbara, will be decommissioned. That’s going to be the first platform that’s been decommissioned in California in over 20 years.

Do you see a scenario where all 27 oil platforms will follow the Rigs to Reefs decommissioning program?

Emily:

Each platform needs to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Some platforms are shallower, some are deeper, and some aren’t in ideal locations. If they are at the base of a river mouth, there’s a lot of sedimentation, it wouldn’t make an ideal candidate for a reef. I think that at least 30 to 40 percent of the platforms could become reefs.

Platform Eureka offshore of Long Beach, California. The superstructure is home to mussels, strawberry anemones, and several fish species. Photo Courtesy of Blue Latitudes.

How many oil platforms are out in the world and how many have been decommissioned according to the Rigs to Reefs program?

Emily:

They’re constantly being erected and taken down; I’d say there are thousands of platforms. They can do directional drilling; one platform might be home to 13 wells or 32 wells. You never know how many wells are actually associated with the platform.

In the Gulf of Mexico, there are probably thousands oil platforms and they converted almost 600 of these platforms to reefs.

What have you learned from founding Blue Latitudes?

Amber:

I’d say that we’ve learned what it’s like to be a woman in business and entrepreneur. Especially in the oil and gas industry, it’s highly dominated by men and especially older men. Not only are we women, we’re also representing the environment.

We’re there to talk about why it’s important to protect the environment and why — when you’re decommissioning one of these offshore oil and gas platforms — it’s important to make sure that they take into consideration the option of reefing and they look at the structure and the life that’s grown there.

Give me an example of a hurdle you have faced while building the organization and what you did to overcome it.

Amber:

I’d say initially having to break that barrier in the industry. What we found is that by sharing the science and communicating the value of the artificial reefs that we’ve gotten a resounding positive feedback from the oil and gas industry.

It’s exciting to see the industry considering this option in greater depth than they have in the past.

Especially on an international level, I was just working on a project off of West Africa. One of the challenges working there was because it is a Muslim country. You walk into the room and they usually work with men only. There was no handshaking; I had to put my hand on my heart and do a little bow. Then when we would get into conversation, it was often me with male colleagues discussing the environmental issues.

We were there for a conference and at the end of the week it was amazing to see how receptive they were and how much they cared about the environment. Especially when we get to issues like fisheries and the importance of protecting that resource.

Initially, there may be some hesitation about talking about the environment in this industry. We found that people have become very receptive to it.

Can you give me an example that indicates that people in the industry are receptive to the Rigs to Reefs program?

Emily:

The biggest comment that we’ve had that is indicative that they’re receptive, is that we keep getting more jobs. That we keep having a variety of oil companies reach out to us. Different governments reach out to us. We just got back from Malaysia; we’re working in Thailand.

Previously in the oil industry the environment was an extra. If you had money for taking care of it — lucky for you. But now the shift has changed, they’re recognizing that the environment is very closely tied to what they do and their ability to maintain their activities. That’s been the biggest shift that we’ve seen.

Emily and Amber in front of an oil platform converted into an eco-tourism hotel in Malaysia. The founders of Blue Latitudes were awarded an Explorers Club flag. Photo Courtesy: Blue Latitudes.

You are very global, where is most of your work?

Emily:

Yes, there are oil platforms in every ocean all around the world. Probably the North Sea and Gulf of Mexico have the most, although South East Asia also has a significant amount.

I’m from the Netherlands, are you working with the Dutch at all?

Emily:

We’ve been trying. The North Sea, at this time, is very anti-Rigs-to-Reefs.

Why is this that?

Emily:

It’s not well received. They are actually one of our target audiences that we are working on to change that perspective.

One of the biggest issues is that because there are so many different countries that all have their own stake within the North Sea. In the Gulf of Mexico, there are all the different states that have their own opinions, but they are ultimately governed by the U.S. government.

Each government has their own policies, cultural identities, environmental policies, and economic schemes. Every single one is very unique. You need to get them all to agree as to what will be the best method for decommissioning.

They also need to take the platforms on shore. So, if your platform happens to be in the Netherlands, a portion of the North Sea, but you need to decommission it on Scotland’s territory, what does that mean?

How will that equate in terms of money and things like that. That’s been the biggest challenge. And the platforms are not well studied; there’s only one scientist who has the permit to go dive on these platforms. He just published his first thesis. There’s not a lot of information like we have here in the U.S.

You’re associated with oceanographer Sylvia Earl’s Mission Blue. What does this partnership entail?

Emily:

Blue Latitudes operate in a dual capacity.

We operate as a consulting firm, a small women owned business, LLC. So we go out and do ecological value assessments. We work on decommissioning plans and we do environmental reviews, things like that generate income.

A huge part of what we do is education outreach, research, and going on expeditions to learn more. A lot of those things you don’t get paid for. We can apply for grants through our partnership with Mission Blue. Sylvia is a big component of the Rigs to Reefs program. It is a big benefit to align our practice with Mission Blue, they receives 20 percent of the grants and donations we receive.

Emily, you worked as a field technician on the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. What did you see that you still carry with you?

Emily:

I had just been reading about the BP oil spill in the newspaper. I had never seen an oil platform. When you see them in person and that up close, they’re just gigantic. When you see hundreds of them on the horizon, it really gives you perspective.

After the spill, BP hired a lot of the fishermen who could no longer work. Obviously, they couldn’t fish or troll for shrimp. The fishermen were the ones driving our boats as we were collecting water, sediments, and potentially oiled biota samples. Every single day they would be raving about the fishing on the [oil and gas] platforms — how they couldn’t wait to go on vacation and go fish on the platforms. Which, at the time, seemed a little ironic.

They were saying, “Rigs to Reefs is a great program!” It was the first time I heard about it. That I ever even considered that there’d be a reef on those platforms. It was one of those things that now seem obvious, but at the time I couldn’t have even imagined that there’d be life living on those platforms. That stuck with me, to think a bit differently about what’s out there and what our resources are.

Amber, as a previous ocean curator at Google, what was a surprising learning for you about the ocean?

Amber:

We were working with different groups, universities, and nonprofit around the world. One of my jobs was to go around and take their stories and relate it into something we could easily share with any audience.

We would add these stories on Google maps and create this interactive educational layer. I was constantly learning interesting things about the ocean. My greatest take away from that experience was learning how to communicate ocean science to the general public.

One of the, if not the biggest, challenges and one of the things that attracted me the most to Rigs to Reefs is that it’s not black and white. It’s not a Save The Whales. It’s not an easy thing to understand, but there is true value behind it and the science is there. It’s an exciting challenge — creating a campaign and talking with people about this issue. Encouraging them to look at these platforms as something that could be beneficial for the environment.

How did you realize that communication would play a critical part in meeting your goal?

Amber:

I was doing my undergrad research on barnacles. It was a very specific field with a lot of terminology. I would go to the dinner table with my family and try to explain what I was doing. I found that it was really hard to get them excited about it. I was like, “Man, if I can’t communicate the value of this science that I’m doing, then does it really have any value at all?” I decided to look for an opportunity that would afford me the chance to learn about communicating ocean science and talking to people about it in a way that gets them excited, so that we can share together in our love for the ocean and our desire to protect it.

How is it to work together? You met in school, starting a company together is a whole different ball game. How do you make decisions?

Emily:

I spend more time with Amber than I do with my own fiancé. [Laughs.]

We work together. We travel everywhere together. We do lectures together. We’ve realized how strong we are as a team. We both bring very unique things to the table. To have someone else when you’re just not feeling it that day, you have someone there to pick you up and encourage you. Then you take on that role too.

A really big part of what we’ve achieved is because we have very different backgrounds, which has played off of each other quite nicely. It aided us in forming the company. A big part of it has just been luck; we get along really well. Amber is my maid of honor! [Laughs.]

What’s next?

Emily:

Well, we are getting really excited about the decommissioning of Platform Holly. We are also looking on the East Coast to wind farm that are being placed offshore and have this new form of clean energy.

It’s interesting because on the oil and gas side, we work on the end stage of life, the decommissioning. When it comes time to remove these structures, we’re going to look at the reefs and decide if Rigs to Reefs is the best option.

These wind farms turbines are below the surface and supported by three pilings that go all the way down to the sea floor. It looks very much like an oil platform.

It’s likely that those structures will form the same kind of artificial reefs that we see with offshore oil and gas platforms. What we’re working on is to encourage these companies to think about the site when they place these structures. Is there any way that we can have a win-win, not only collecting energy, but also placing them in an area of ecosystem need? An area where there’s been environmental destruction or over-fishing?

That’s what we’re looking at right now, and we’re pretty excited about that.