The SCAN Foundation President & CEO, Bruce Chernof, on Long-Term Care

BY PAKSY PLACKIS-CHENG

Long-Term Care, something we don’t discuss until often it is too late. Many of us face complex and costly long-term care with either our loved ones or in our own cases. Dr. Bruce Chernof, President and CEO of The SCAN Foundation, focuses on improving the long-term care for older adults that preserve dignity and encourage independence.

Recently, The SCAN Foundation, together with The Commonwealth Fund, the John A Hartford Foundation, Peterson Center on Healthcare, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation partnered to offer higher-quality and more affordable care for high-needs and high-costs (HNHC) patients. Specifically, these five foundations are collaborating to clarify the needs of HNHC patients, demonstrate the best ways of caring for them, and assisting with the spread of proven approaches.

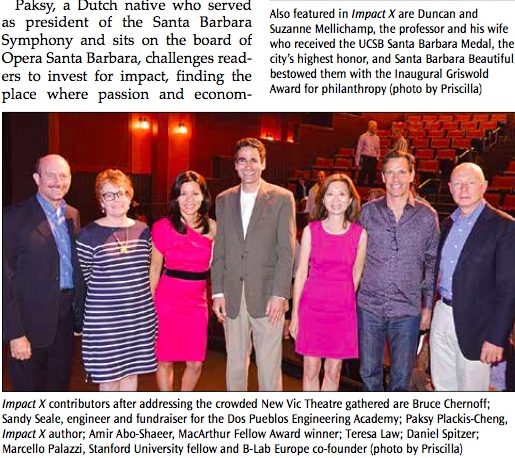

Dr. Bruce Chernof, President & CEO of The SCAN Foundation, also spoke at the Impact X book launch about improving the quality of health and life for seniors.

Dr. Bruce Chernof on the left, one of the special panel speakers and interviewee from Paksy Plackis-Cheng’s book, Impact X. Article from the Montecito Journal.

The original interview from the Impact X book:

impactmania met with Dr. Bruce Chernof shortly after the Federal Commission on Long-Term Care (LTC) presented their report, and during the government shutdown, at his home and vineyard on October 4, 2013. Chernof served as the Chair of the Federal Commission on LTC.

The federal commission presented a final report with an assessment of long-term care services and made recommendations on future policies. How do you feel about the commission’s work?

I feel terrific… It was interesting to see Democratic and Republican appointees come together to agree on 28 solid recommendations. That would transform the system of services for vulnerable older adults and younger people with chronic disabilities and illnesses. You can see in the report not only a way to make the system better today, but [also that] there is a clear pathway toward building a new financing strategy going forward—and one that builds off the public and private sector.

There is the report. There are findings. How do they get implemented?

The Senate Committee on Aging will hold a formal hearing the 23rd of October, assuming that people are back to work [from the government shutdown]. That will begin a discussion in Congress about how to handle the recommendations. So that’s one important step. For the advocacy organizations that care about younger people with serious disabilities — those organizations need to speak up and own these recommendations because given the challenges that are faced at the federal level, it is going to take outside advocacy to push and care. The last really interesting thing about the report is it calls out the important role of the private sector… [which] has been somewhat stymied in making changes. There is an opportunity for the private sector to step up. It will not happen without all sectors coming together.

Is there a clear solution?

Speaking for me, as opposed to on behalf of the whole commission, there’s a very clear path forward. There is a role for the public sector, both Medicare and Medicaid. There are things about the way Medicare and Medicaid operate that need to be fixed that are not person-centered and are in poor use of resources. If we could sell long-term care insurance that was tied to say, life insurance, or disability insurance, so that you are buying a product that was more about protecting the arc of your life… so in your younger years, what you’re really buying is a bit of life insurance and a little bit of disability insurance. Then over time, those balances might change. When you’re 50 or 60, you’re buying a lot less disability and more long-term-care coverage, so you’re starting to position the pro- duct differently. I think that would go a long way toward making products more meaningful in people’s lives.

Why is there so little visibility around this issue? People don’t think they will become older?

This is something that generally people don’t want to think about. There is that kind of lens [of] a culture that’s way too interested in youth. [Also] we still have this sort of faintly 1960s view of aging. We want to believe that we’re going to live our whole lives, and then something will happen: We’ll develop heart disease, or have a stroke. We’ll just sort of fall off the cliff. In 1970, most people didn’t survive heart attacks or major strokes, most of cancers weren’t curable, so it isn’t entirely unrealistic that in our own cultural memory, most people lived until they had a very serious event. That actually isn’t at all how people live any more, and we as a culture… still have this cultural memory which isn’t wrong, it’s just out of date.

And then, I will say the policy, research, and health care communities have completely damaged the discussion around aging. If you look at what’s been written in the past 20 years… it’s always been about sort of death and dying, and dying the good death [laughs]. “If we could just do shock and awe, we’d get people’s attention” is completely wrong. What’s really important is that the older people define themselves by the function they retain, not the function that they’ve lost. And so, the problem with the “let’s die a good death” discussion … It is all about the loss of function.

Is there a country that has health care figured out?

The short answer is nobody has solved this problem. There are countries that have at least accepted that everybody needs health care, and that health care needs to be paid for. The British or Canadian system… They make sure everybody gets coverage. For those people who want more, they can buy more. Japan is actually the same way; basically, there are three insurance companies. It’s more like a utility. People are covered, but it’s predominately through a private insurance.

The real tension … is that you are setting up a big bureaucratic system that’s run out of one place. That doesn’t make it particularly responsive to all parts of the country. How does a community come together to be responsible? It’s not just about moving money around. … It’s actually about a level of community support and involvement.

Then there are countries — most of which are in Europe — they’ve done a lot more thinking about aging successfully. You can go to a little walled town in France, for example. There’s nothing ADA-compliant about these towns (nor will they ever be), but older vulnerable people thrive in those communities. Somehow they get up and down the stairs in those communities. They deal with those cobblestone streets. I was really taken by being in these little towns. … It’s predominantly older people [who live there] because younger people are generally out working. But it’s not like all the older people are carted off to nursing homes. … There is something very peculiar about American thought that’s…somehow our model is different enough that those rules don’t apply.

You’ve successfully led a bipartisan commission. How do you realize a respectful and impactful collaboration?

I think we have one really important thing on our side: Aging is not a partisan issue. … No matter what elected official you talk to, they can tell you a difficult story of their own family, whether it was caring for a parent with Alzheimer’s or a child with Down’s. There is a way to begin a discussion with every person…

They probably disagree on the solution.

That, yes, but you start with a person’s centered perspective, which is, everybody should have good care… That will set you on the path to solving problems. The public sector is never going to go away. It needs to function well. It’s a very important part of the system. And the private insurance market is broken. It needs to operate in a way that’s way more accessible to people, even if it isn’t a perfect solve for everybody. I think long-term care will never be fixed as a stand-alone problem. It will only be fixed in a context of addressing Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security. And as a country, we’re going have to have that discussion.

Why this issue?

I guess… I’ve been chasing the same professional question for 25 years — literally since I was in medical school — which is, how do you build sustainable systems that meet the needs of vulnerable populations, and how do you judge quality in those systems? So the fact that it’s up and running doesn’t necessarily make it good. Chasing these large, inscrutable, and unanswerable questions is what it’s all about.