Penelope Gottlieb

BY PAKSY PLACKIS-CHENG

Penelope Gottlieb, an Emmy-Award-winning graphic designer turned fine artist, spoke with impactmania about painting angry flowers and how she started building archive of extinct plants.

You created numerous title designs for film and TV. Tell me about your work as a graphic artist for the film industry.

I went to the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, CA and was an illustrator for many years. Title design was always attractive to me. At age 23, I showed up for a job interview with five men in suits in Century City (Los Angeles, CA). It turned out to be a motion picture title sequence for the ABC Motion Picture feature film division. They needed a new logo and said, “Can you do this for us?” And I said, “Sure!” [Laughs.] I had no idea how to deal with action and movement.

I came up with a concept that they bought, which was a 20-second introduction to all of their movies when they screened in theaters. It worked out so well that I received more referrals and job offers.

It was a fun chapter in my life. However, in the late 1990s, I had to find out where I wanted to go as an artist, since up until then I was always solving someone else’s problems. I never had time to realize my own vision.

I decided to go back to school and finished my MFA at UCSB in the Department of Art. After graduating, I entered the world of galleries in order to create my own body of work. In the beginning it was exciting, but also a little scary, when you don’t have any outside direction, what will you paint? While I was formalizing my goals, I learned that a growing number of plants were becoming extinct. I began to research this subject out of curiosity. I didn’t realize at the time it would become my life’s work.

Is there anything you learned as a designer in the film industry, —a corporate environment— that you bring to fine arts?

Yes. One of my first lessons was collaboration. Though I am not dealing with it too much at present time, it was a very interesting process: listening to people, interpreting, and finding solutions together. I also learned about work ethic and how to be professional, problem solving was done very differently — by working with committees.

Give me an example of how you solve problems in the work you’re currently doing.

I guess it’s very self-indulgent, because I get to pick what interests me. I like having the luxury of time to really think about processes and projects. I have a developmental stage during which I can experiment.

As a commercial artist, there were so many deadlines, I had to come up with a solution that would work in a really short period of time. It was almost impossible for me to navigate and find deeper and more layered solutions.

Was the extinction of plants, the main series you’re still working on, one of your first projects?

I had a few other series, but it is the one that stuck with me. I did a series of drawings on residential architecture, because the notion of how people identify with their environment really interested me. These drawings were about the American dream of home ownership. The series was based on photographs from the real estate ads in the Los Angeles Times: the linguistic hype of sales in those ads and visual disconnect of reality that went with them. The series was exhibited in mass salon-style groupings.

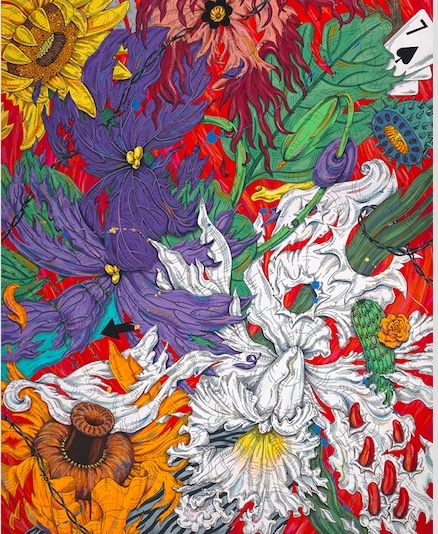

Penelope Gottlieb’s work in the Edward Cella Gallery, Los Angeles.

What is the long-term goal of the plant series?

My long-term goal is to record plants as they become endangered and extinct. I found that a number of these plants did not even have an identifying photograph or illustration. In the early-20th century, plants were often never recorded before becoming extinct. The only record we have is a description made by a botanist in the form of field notes. Lacking visual references, I have attempted to recreate these extinct plants from language. They became a metaphor for loss.

In the themes you covered in your work — real estate, identity, and environment — you are responding to cultural, social, and economic forces. Tell me a little bit about why that is important to you.

First of all, I wanted my work to be contemporary. There is a lot of history around painting plants and in other words, a lot of baggage. People have painted plants beautifully for hundreds of years, but they reflect the time in which they were painted.

When I look back historically at Dutch and Flemish still life paintings, they are very calm and have a sense of balance. This kind of security is missing in my work. I feel that we are in a moment of environmental chaos, and I want my paintings to reflect my vision of nature at this present time. I was talking with Bruce Robertson, (Professor and Director of Art, Design, and Architecture Museum, UC Santa Barbara), who made an observation that I appreciated. Bruce said I am engaging in an art form — flower painting — that was historically relegated to women. It was appropriate for a nice lady to paint a nice flower. I wanted to paint flowers, but I didn’t want to be apologetic about it. They did not have to be pretty pictures of polite flowers, but could be dynamic and carry a message. It took me quite a long time for me to figure out how I could navigate the subject in a way that would have impact and be satisfying to me.

Lycium Verrucosum – extinct. Acrylic and ink on paper (60″x 40″).

So how does a woman paint flowers today?

With anger and with a shout! I intentionally painted these flowers as being attacked and torn apart. They are trying to survive extinction though many of them have lost the battle already. There is an extinct violet from France, Viola cryana, that is being shredded. There is also weaponry inside: barbed wire, knives, and energy.

Viola cryana by Penelope Gottlieb. The Viola cryana was first discovered in 1860 and went extinct in 1950.

I hope that when you look at my paintings from a distance, the pretty colors attract you at first. As you get closer, you might ask, “Why are these plants in such distress?” That might drive you to read the wall text, or to ask a question, and finally to find that these plants are all extinct. These paintings are of the ghosts, in a way, that are left behind.

Some of my new paintings are also ghost-like in their finished surfaces. I paint on aluminum, which is a very reflective surface. By stepping close, you see your own reflection. That might bring a couple of thoughts, such as, their fate is our fate. We are complicit: plants are becoming extinct because of man-made issues.

I am wondering where people go from here. Where do they take their concerns once they realize these plants are extinct?

This is a very daunting question, and I often think about it in my own life. How can I make small steps? What can each one of us do? If we all take small steps, like recycling and conserving energy, then everyday small actions can add up.

Fifty percent of all plant species will be lost in this century. We are in an extinction phase right now, the sixth in the history of our planet. This however is the only extinction incident that has been caused by a living species…man.

Are you saying that all the other five extinctions were part of natural evolution and this one is manmade?

The other extinctions were due to catastrophic events, like a volcanic eruption or meteor strike. Momentous things happened and changed the future of the planet for millions of years. This particular extinction is mostly due to manmade reasons such as global warming, loss of habitat, and invasive species.

If you think of life as a pyramid, plants are at the bottom, because we all depend on plants. You hear about an endangered owl or a panda on the news, but people do not discuss a much deeper problem, which is plants. We all need them to live.

How did you come across these extinct plants. There must be many of them?

It was interesting. When I first started, and that was in the 1990s before the Internet, I went to the Santa Barbara Botanical Garden and met a wonderful botanist, Dieter Wilken. There was a tiny library with musty old books and Dieter Wilken assigned me to a research librarian.

The problem at that time was navigating the research material. Many research centers said they organized material temporally, but their efforts were underfunded. It was difficult to stay current with statistical information. Confirming a plant’s status is very important to my work. A confirmed extinction means that the plant must be extinct in the wild for a minimum of 50 years. However, sometimes you might think a plant is missing, and then a small population is discovered. Also plants are becoming extinct all the time but might not yet be on a confirmed list. This is why I must double- and triple- check all the information I gather. I am mostly looking at plants that are extinct from around the mid-20th century and earlier. Unfortunately, the list keeps growing and my work is far from done.

Sometimes when you research an extinct plant’s name on the Internet, my paintings appear! In this way, I have embedded my artworks into the archive in an unusual way. These paintings are not meant to be a naturalist’s depiction of botanical accuracy, but rather a poetic memory of things lost forever.

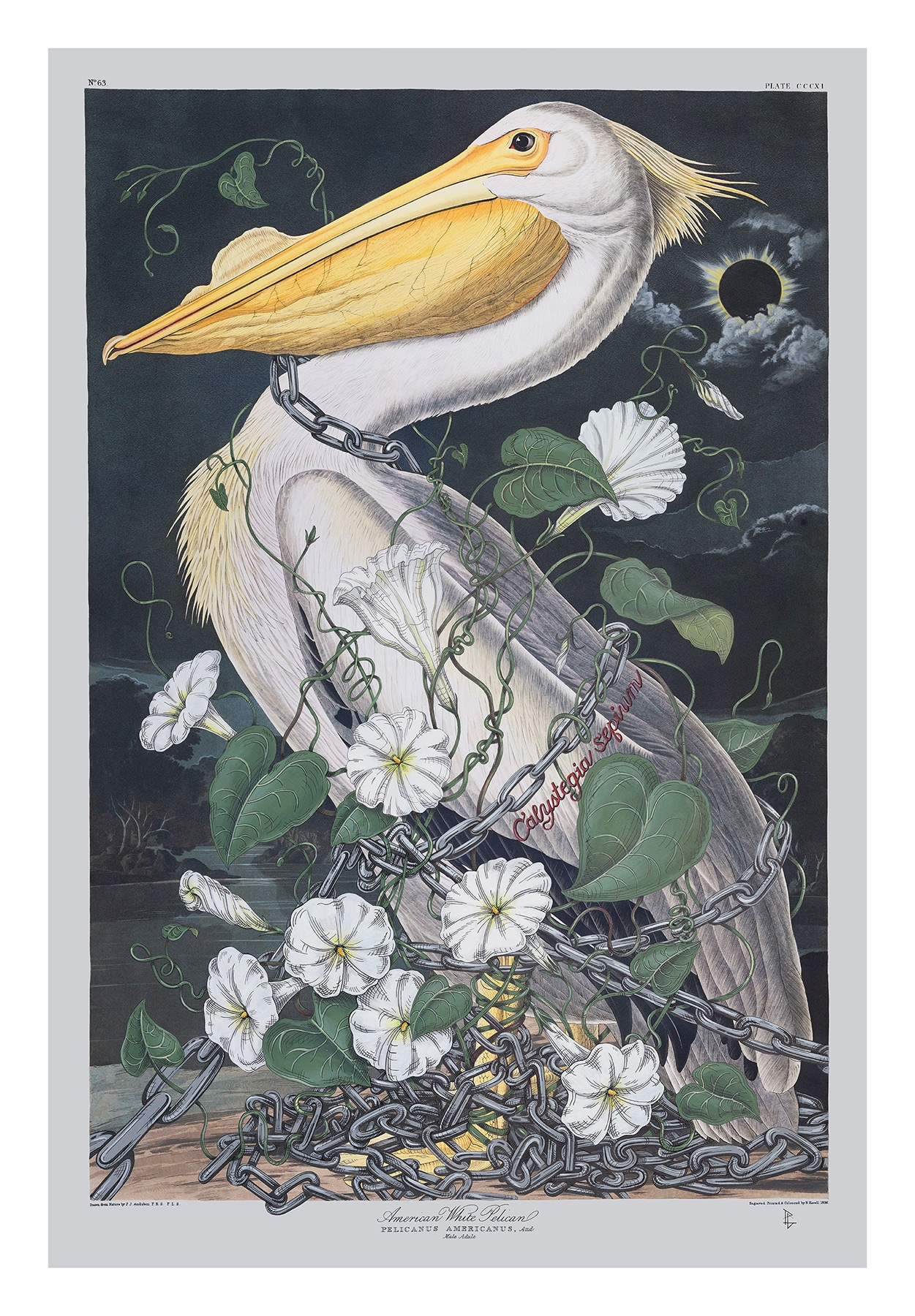

Calystegia Sepium

How many plants have you recorded?

About 100 to 200, I also work with endangered and invasive plants.

In my appropriation paintings, I selected plates by the naturalist John James Audubon from his iconic publication; The Birds of America (1827-1838). I reconfigured his original paintings with my own comments on nature in the form of invading species entwining and strangling the birds.

I chose John James Audubon because he was a famous naturalist of his era. It was a perfect opportunity for me to engage in a dialogue with the past. His view of nature is very contradictory to a contemporary vision. As he was creating his masterworks, he also exploited the very nature he so loved. The concept of extinction was not even a conscious thought. The specimens that he painted with such wonderful animation were in fact his own taxidermy. He was quoted as saying that “A day without shooting 100 birds was a day wasted.”

Any parting wisdom for students, artists…

For me it [the greatest challenge] was finding a subject to spend time and energy on that I felt was meaningful. I didn’t want to just paint for the sake of the process; I wanted to have something to say.

I was speaking with students from UCSB last evening and gathered their main struggle is how do you arrive at that “something?”

Absolutely! There is no clear avenue because everybody must take his or her own path. The meaning of one’s own work must ultimately come from within.

My journey came out of personal experience. I never wanted to paint my biography, that is, to paint my life story. But when I experienced loss in my life, I became interested in the subject of loss. The plants became a metaphor for loss and also a stand-in for something that was very meaningful to me. It is not necessary to tell your whole story, because it is private, and sometimes it seems self-indulgent. You can say it differently and people will relate to it in their own ways.

Penelope Gottlieb’s mother Betsy Brown was one of the first professors to teach puppetry at the university level in California and possibly in the United States. The large puppet is an antique from Belgium circa 1810.

Is this in reference to the loss of your mother?

Yes. A few months after her passing, I had to go look at a photograph of her, because I could not remember the details of her face. It was really pretty scary, and I thought, “Loss is so final.” As I began to think about and research extinction, the image of a plant became the stand-in for the image of my mother without having to be literal.

At present, I am very engaged with exhibiting my work and interacting with scientists and botanists. I often present my work and research alongside a botanist, sometimes in an art gallery, sometimes in a botanical garden setting.

These kinds of opportunities have opened up a whole new world for me. To speak about nature and preservation is a real gift.

Penelope Gottlieb’s Upcoming Exhibitions

May 4 – August 12, 2018 Chicago Botanic Gardens, Chicago, IL

May 10, 2018 JoAnne Artman Gallery, Chelsea, NY

June 15, 2018 Gerald Peters Gallery, Santa Fe, NM