Fluency Lighting for a Brighter Future

BY PAKSY PLACKIS-CHENG

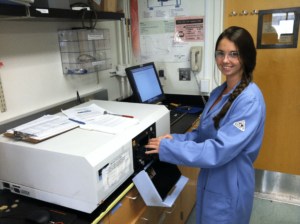

Kristin Denault developed an energy efficient lighting technology while studying Materials Science at UC Santa Barbara. Her work on laser diodes will serve as a strong alternative to LEDs. Armed with this intellectual property, she founded Fluency Lighting Technologies.

Denault shares how the future light source will not only emit light, but transmit secure and fast data, what bootstrapping a startup meant for her, and how there is no official certification standard for her technology yet.

Kristin, why lighting?

It happens that the group at University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) had a project in lighting. It was really interesting to me to study the very basics of science while it has an application that’s so widespread and useful in society.

What is unique about Fluency Lighting?

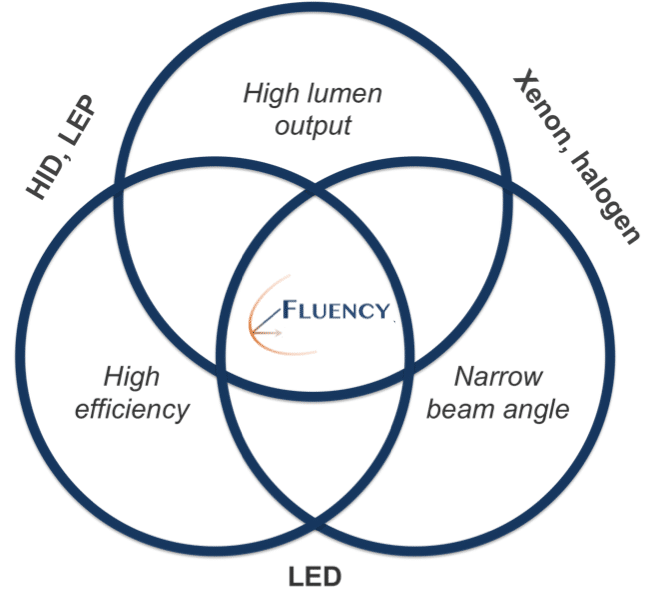

At Fluency, we’re creating next generation energy efficient light sources. They’re similar to energy efficient LEDs that are being used in our homes and in the workplaces. Instead of using an LED, we’re using a laser. This allows for higher power and brighter light for applications like outdoor street lighting and stadiums where you need a lot of light. LEDs are having trouble providing that with high efficiency.

There are many universities, institutions, but also commercial entities that are doing R&D in lighting. What were the first steps you took to build this company?

The very first building block was through UCSB, at the Technology Masters Program, taking short business courses while doing my science career. It got me thinking about how to apply the research and commercialize it, because we were seeing very interesting results in the lab.

Then, connecting with mentors and advisors who have grown businesses or founded startups. The next step is going out and talking to potential customers for the product, and seeing if it’s something that people really want and need.

We’ve been fortunate enough to have the Federal government grant from the National Science Foundation. That has really given us the opportunity to build prototypes.

A lot of times with hard science and technology startups it’s difficult for investors to put their money into something so early that hasn’t been proven yet. At the same time, to take something out of the university, out of the lab, you need funds, and you need some sort of funding to help locate that.

How did you take it out of the lab? When you are speaking with potential customers, they don’t know what is beyond what’s on the market.

What we did is to first have an idea of what the technology can provide and the benefits that we think are important. Then, when we talk to customers, we ask them, “Okay, what are your problems with your current lightings system right now? What is the biggest issue for you? If you could have anything in the world that would be an improvement, what would it be?”

What were the biggest issues?

One of the main markets that we’ve been exploring is entertainment, spotlighting. We’ve gone down to some of the production rental companies and manufacturers. Their biggest thing is that they wanna provide their clients on the stage and in the audience more light for added features.

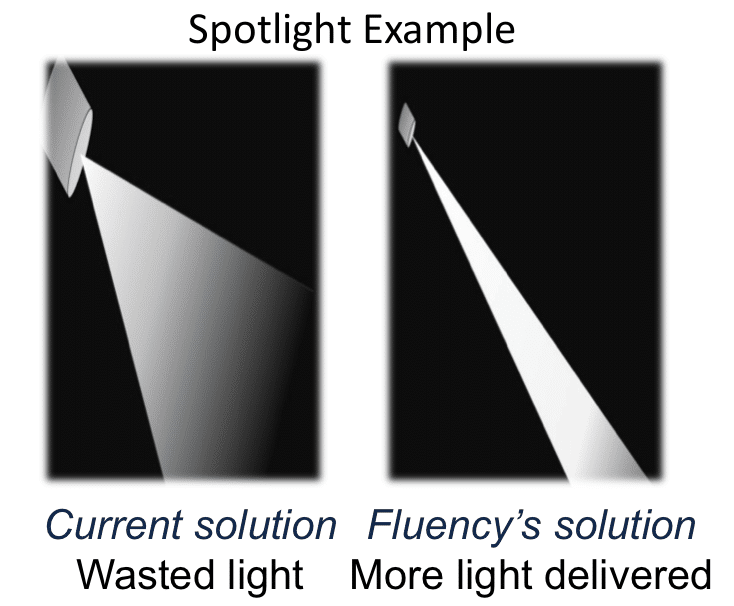

They want to have a good show and a good performance and part of that is having more light. The issue is that they are limited by the electricity constraints of a building. A more efficient light would mean they can deliver more light under the same electricity constraints. Another important aspect is they have these giant spotlights in the back of the theater. They want all that light delivered to the stage, but this is so far away, you lose a lot of that light along the way.

We’re able to create much more narrow beam angles, a narrow spotlight. So that means that more of the light from the very back can be delivered to the stage. So you’re using less energy and you’re delivering more light.

What are the costs compared to what they’re using now?

That’s something that we are exploring right now. We have our own ideas about the materials and the processes that we want to use to manufacture.

Starting with the laser source itself, the laser is more expensive than LEDs. So we wanna make the optics, the reflectors, the lenses that are needed. Once those are complete, we’ll have a better idea of our cost.

Another benefit that goes into the cost is the lifetime of these devices. They’re using halogen sources, which have a lifetime of about 1,000 hours. The lasers have a lifetime of 50,000 hours. They have to replace the halogen sources very often. When you have a theater setting, you have all these catwalks. It’s very difficult maintenance and a lot of man-hour costs.

How did you go about securing a $50,000 grant?

I wrote the grants myself. Being a graduate student and having some academic grant writing experience was helpful. In the same sense, writing grants for a business is a lot different from academia.

One of the biggest comments from one of the grant reviewers was that the grant proposal reads like an academic proposal. [Laughs.]

I guess writing to the National Science Foundation was kind of a nice transition. We had two grants from the National Science Foundation. The first grant was an iCORE grant, Innovation Core. That is a really interesting grant. It’s a grant that is engaged towards students in a university setting who want to commercialize their product.

The grant actually goes to the university. I partnered with UCSB. You form a team of three. The student is usually the entrepreneurial lead. Then you have the primary investigator from the university and an industry mentor.

It’s like a seven-week short course of how to go out and conduct interviews with potential customers. How to make sure that the technology you want to bring out of the lab is something that people in society actually want.

What is the process of certification in the lighting market?

Yeah, there are some certifications needed. It is tricky that this is a new technology, and a new product that is not on the market in the US. In Europe, they are getting a similar technology that’s based on lasers for car headlights.

Right, for BMW?

Right, BMW and Audi. They haven’t been approved in the U.S. yet, but it’s a good start to see that some countries are allowing that. I’m sure it’s being worked on in the U.S. right now. As far as what I’ve discovered, you need testing for your electrical supplies and connection, that it’s not going to explode or start a fire. I talked to the regulatory bodies, they need to develop some new tests and new standards ’cause it’s a new technology.

Tell me about the impact on the industry. What are you hoping to bring with this new technology?

There’s a ton of applications for this technology, which is really exciting and great. At the same time, as a startup, you need to choose something and focus on it.

The biggest impact is on energy and electricity saving. Even though we’re starting with the entertainment industry where they want more light, there are a lot of other industries that this technology can be translated to. One of the reasons we’re not starting with those is because they usually have stricter budgets and they want technology that has been on the market for a while. Look, for example, at a stadium, seaport, or an airport, where they’re operating 24/7. They are operating high-powered lights. They’re using a lot of energy and electricity.

Sometimes street lights can be LEDs, but some of the other high lighting, they’re typically not LED, because they’re too far off the ground for LEDs to really be beneficial. Those are the applications that we can make drastic energy statements in.

It sounds like laser lighting is reliable; it saves energy; what are some of the other qualities?

Yeah, a higher energy efficiency, longer lifetime, those are the basic ones. Then down the road in the future, there are also some other really exciting benefits, which tie into the Internet of Things. It’s having your light bulb and your light source in your house be more than just lights, but also be a source for other sensors and things.

One of the things that this technology can do is called visible light communication. It’s similar to Wi-Fi, but instead of using the wavelength and frequency you’re using in Wi-Fi, you’re using the actual light. And so, if you are on a college campus by one of those information kiosks that light up at night, you can walk over with your phone and the light at the kiosk could be transmitting information to your phone. It could be telling you what time the bus is coming.

Light can’t travel through a wall, all your data transmission can be much more secure, and you can also get much faster speeds than you can with Wi-Fi. This is interesting for government and military applications, and for underwater communication. There’s lot of interesting benefits that this technology holds that are even more than just lighting.

A lot of entrepreneurs have talked about bootstrapping their company. What has that meant for you?

For me, government grants have been great. Without them, I probably wouldn’t be where I am right now. Before government grants and before we had any sort of income, a lot of the patent expenses had been paid for by myself.

Government grants are also a form of bootstrapping in the sense that you haven’t given any equity away yet. I’m grateful for the grant, that it gives the company a much better footing for when we do raise money through investors.

How many times have you wanted to give up?

Every time I run out of money. [Laughs.] Not really. You have your good days, and you have your bad days. You just have to make sure that when something exciting happens that you do just take some time to celebrate and appreciate that. That helps keep you going on the bad days.

Who has left an imprint on your professional DNA?

That would be Ram Seshadri, his teaching and support through grad school and my development as a researcher and a scientist have been tremendous. Then also after grad school, his support with even just meeting for coffee and catching up and asking me how things are.

Are you from a family of entrepreneurs?

I’d say I’m the first entrepreneur. I do have a bit of an engineering background in my family: my mom and dad worked for the telephone and electrical companies in New York.

The start of my career was at 12-13 years old. I had a little hair braiding business. We used to go to Ocean City, Maryland every summer. One year, I had two of my friends come with me, and we had a hair braiding and hair wrapping business. I was the hair braider. We printed out fliers and handed them out to people. We actually got some people to come. [Laughs.]