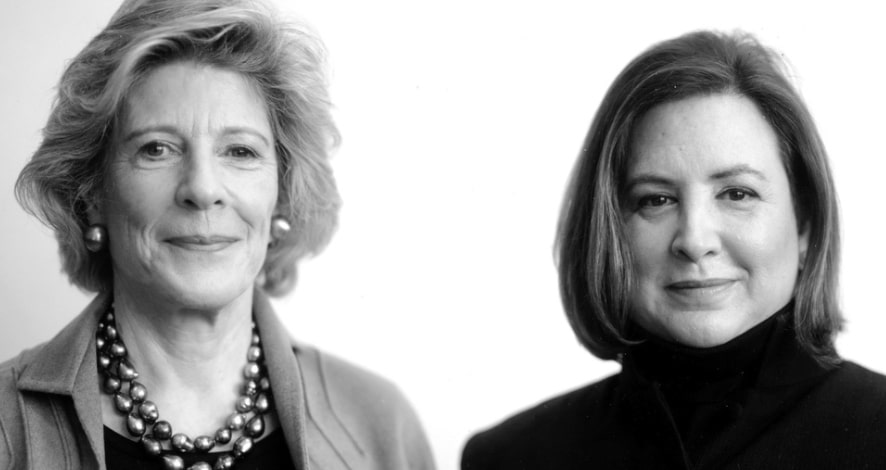

Elizabeth “Buffy” Easton, Director of the Center for Curatorial Leadership (CCL), which she co-founded with president emerita of the Museum of Modern Art, Agnes Gund. Photo courtesy of Center for Curatorial Leadership/Judith Joy Ross.

Since 2007, Elizabeth “Buffy” Easton has been the Director of the Center for Curatorial Leadership (CCL), a not-for-profit organization she co-founded to train museum curators in the fundamentals of management and leadership. CCL identifies individuals who have the potential to become leaders and provides the tools for them to not only take charge of the art in their care, but also assume the leadership responsibilities essential to high performance in today’s art museum.

While other organizations teach management skills to individuals working across nonprofits and museums, CCL has become internationally renowned for its unique curriculum specifically geared towards training art museum curators.

Since its inception CCL has prepared over 100 curators to assume positions of greater leadership, over one-quarter of whom have gone on to direct museums and other cultural institutions. For the ten-year anniversary of the program, Elyse A. Gonzales, a Fellow in the 2017 class interviewed Easton about the founding of the organization and her hopes for the CCL’s future.

BY ELYSE A. GONZALES

Can you speak broadly about the experiences that led you to form CCL?

When I was at the Brooklyn Museum, there was talk of founding an organization for curators — what later became the Association of Art Museum Curators (AAMC). As the first elected head, I devoted a lot of my energy to thinking about the big questions facing curators beyond my specific job as head of European paintings.

For one of AAMC’s annual conferences, we invited a panel of board chairs from major museums. Curators rarely interacted with these individuals and I wanted them to hear from these incredibly powerful people. This included the chairs of the Cleveland Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, and President Emerita of the Museum of Modern Art, Agnes (Aggie) Gund.

Somebody asked, “Can curators become directors?” Aggie Gund’s response was: “Among six searches in which I participated to hire a museum director I’ve noted a pattern: the A-list is the list the committee wants, the most famous directors in the world. The B-list are the people the committee hopes to end up with, because there is a sense that you want them and they want you. The C-list is those people who want you, but you don’t want them. And then there’s the D-list. That’s the curators.” Hearing this, many curators were shocked. This prompted an important line of inquiry for me: what would it take to make curators into directors?

Center for Curatorial Leadership founders Agnes Gund and Elizabeth Easton. Photo courtesy of Center for Curatorial Leadership/Judith Joy Ross.

The first person I met with was Emily Rafferty, the president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met). I told her how unhappy curators were that they’re told they cannot get directorial jobs. Is there any way they can cross the divide to administration and learn things that would make them better candidates? She said, “Of course.” She met with me every six weeks thereafter. We discussed and strategized what source of instruction would make a curator more qualified.

And then, I was having lunch with Gary Tinterow, former curator and department head at The Met, and a founder of the AAMC, when Philippe de Montebello, then director of The Met, walked by. Gary asked him if he would ever support an endeavor to train curators to become museum directors. Philippe was quiet for a really long time. In the end he said, “Yes, I would support it.” That was amazing because with Philippe and Emily’s support, the director and the president of The Met, I was able to go to Aggie Gund and say, “You support curators — would you support this initiative as a co-founder?” And she said yes.

I then remember having a meeting with Emily Rafferty, Aggie Gund, and Philippe de Montebello in his office. They all said, “We will support this initiative but who’s going to run it?” And they all looked at me. At that moment I had to admit that I was going to leave my job and take this on. But it wasn’t until then that I realized what I would be doing.

What were the ideas or ideals guiding your mission, curriculum, and goals?

I wanted something that was unquestionably moral, to put art first, to have the highest standards. I really believe in that.

This program is known for training curators to be museum directors, but you have said on many occasions that this isn’t always the end goal for you.

Not by any means. In the beginning I said we were training people to become museum directors, and we were explaining this program to acting directors to get their input. This was a good thing because all of the directors started to pay attention. I think had I said that we want to teach skills to curators, then nobody would have really listened.

But, yes, our metrics in that regard are fantastic; a quarter of the people who have come through CCL are now running institutions, which is pretty amazing. But, that ceased to be a primary goal. At first it was, but these ideas soon evolved. I’ve felt that it’s less about bringing privilege to people who are already in a position to succeed and more about how these privileged people can be responsible to their profession and their field. It’s so inspiring, the moments that we have with leaders in the field, because they say some of the most frank and honest things I’ve ever heard from people in those positions.

Now, I would say I’m much more aware that the CCL is a journey of the self. It’s a very personal thing in which people come out with far greater self-knowledge. Once they have greater self-knowledge, they’re more understanding of other people and they know better how to lead.

Did you always know that would be a major focus of the program? The self-knowledge part.

No, no, no, that totally emerged for me. Now I pour much more time and effort into that aspect of the program. I mean, don’t you think having done the program that there was a lot of energy devoted to that?

Absolutely! When I talk about CCL to other people I always say that CCL helps you understand your strengths and most importantly, your weaknesses. This is truly transformative information. As curators we rarely, if ever, spend time considering those foundational concepts of leadership.

Another unique aspect of CCL is the Diversity Mentoring Initiative, which requires Fellows to develop a program(s) to help encourage underrepresented groups to connect with and embrace museums or consider leadership professions in museum—curators, directors, conservators, and educators. Can you talk about how that became a part of CCL and why it’s such a big passion of yours?

Five years into the program I felt we needed a reboot. And I rebooted in a lot of ways, which forced me to rethink the program. I felt very keenly that we were serving such a narrow group of curators. The demographics were insufficient for me. I was getting older too and realizing that there were responsibilities that went along with privilege. I was really aware of the gift that this program gave to people and I felt that we really had to change this up. We can’t keep giving the same people who have all these opportunities more opportunities.

I knew we had to change, and it came to me during a quiet moment with myself. I knew this was a moral imperative. I have no reason for doing this, except that it is what we must do. There were no concrete outcomes; it was not about metrics or demographics, but rather this being something that we have to do. Ever since then, I’ve been more and more convinced that this is one of our primary focuses. Training the Fellows is just the path to get there. It’s the means to the end. It’s not the end.

Center for Curatorial Leadership Class of 2017 Fellows (from top, left to right): Naomi Beckwith, Emily G. Hanna, William Keyse Rudolph, Pierre Terjanian, Sarah Meister, Sophie Hackett, Elyse A. Gonzales, Christina Nielsen, Thomas J. Lax, Alison Gass, Jen Mergel, Amy S. Landau. Artwork: Glenn Ligon, Give Us a Poem, 2017. Gift of the artist, The Studio Museum in Harlem. Photo courtesy by Center for Curatorial Leadership/Isaac James.

What does success mean for CCL now?

For me, it’s now evolving even beyond leadership skills and the diversity initiative because I see other issues like governance that need attention too. I’m not completely switching my gaze, but we could start to think about this question of governance.

And when you say governance, you mean –

Well, it’s not just leadership on the part of the director…it’s the board. There’s a lot that we need to consider in terms of how the different parts work together.

I was very struck by how everybody is working towards greater equity and inclusion, but nobody is talking to anybody else within the same organization or beyond. In museums you are dealing with curatorial concentration, education departments, and territoriality. My conviction is that curators are always the leadership track. But somebody must reach out and start to make something happen so that people speak to each other within different parts of the same institution.

So you’re training people to be bridges between disparate groups, departments?

Yes, that would be my dream.

Who has had the most impact on you and your profession?

Obviously, the CCL team is very helpful, but in terms of considering how we grow and what we do, I listen carefully to Aggie. I think that many inspirations come from haphazard meetings with people who are unrelated to what I do because I feel like the greater embrace of the larger world is what makes CCL special.

It is bringing in the larger world that gives us a lot of energy. And it is easy for us because we are small. We don’t have to break anything down in order to build something else up.

Earlier you mentioned that you wanted CCL to have a moral imperative built into the program. I think one of the things that everybody who’s done CCL talks about is the section with Rabbi Bernie Steinberg. How did that come about? What made you think to invite a rabbi to come and speak?

I met Bernie at an awards dinner for my husband. He comes in and says he’s head of Harvard Hillel. I think, “What am I going to talk to this guy about?” It turns out he had been leading the Harvard Hillel for 15 years. He’s a sacred guy and has an aura that’s very special. He changed my life, literally.

During his session at CCL, Fellows are asked to talk about their name and its symbolic meaning to them. It’s an often surprisingly personal disclosure for the participants and it reveals how they are all facing deep, personal challenges even though they are all accomplished people. And then he said, “Buffy, I want you to talk about your name.” And I said, “No, it’s not about me. This is about the Fellows.” He said, “No Buffy, this is all about you.” I remember when he said that, I just thought, “He’s right, this is all about me…. this program.” I think about our ten-year anniversary and what’s going to happen to the program beyond me. It can’t be all about me. And of course, it’s about everybody who participates, but the architecture of it is based on a lot of the counterexamples I experienced in my professional life. But it is also based on the loftiest principles that I hope curators will be able to uphold while doing a good job. I don’t feel there has to be a compromise in order to do good work.

Bernie is one of those people who show that the road is not straight. That you can’t determine an end from the beginning. That you have to deal with a lot of curves, obstructions, and confusion where you don’t know the answer or what path to take. I believe curators are, on the whole, very moral people and if they make mistakes, it’s only because they may not have the strength to dig deep inside themselves and access the strength to do what they feel they know is best. Through his session I wanted to show the Fellows a way of getting to themselves that will give them strength in a time of conflict…to not necessarily make the “right” decision for the end result, but to understand themselves in order to make the right decision for them. I’m not saying everybody who has gone through the program has had an unblemished track record of decision making, but everybody benefits from being true to himself or herself. The people who have been able to honestly embrace what Bernie is teaching, revealing to them, they can access that. I think it’s helpful because there is so much that you can’t know and there are so many factors out of your control.

You have to be true to yourself. I feel this program is true to me.

What do you want to add or change about CCL?

I want to add three things. I want to add more alumni engagement in terms of further learning and produce materials for the alumni that help them build on what they’ve learned. But also for them to interact with each other and form a tighter network so they can all help one another.

Two, I really want to think about governance. I want to better understand and teach our Fellows about the relationship between leadership, staff, and the board. I think about this a lot. It’s important.

And finally, how to further activate the diversity initiative aspect of the program. I want to make it more understandable, feasible to the people who participate in CCL, and I want to better understand the effect it is having on the people it touches.

What’s the most surprising thing that you learned about yourself?

That I could do this. There were some moments in 2014 when we tripled our offerings by adding programs for art history doctoral students interested in museum careers and, in collaboration with the Museum of Modern Art, international curators of modern and contemporary art. I first ran these programs and I had a real crisis. I was overwhelmed. I began to think, if I knew then what I know now, I never would have been able to do it.

I did it as an act of faith, and I didn’t realize what it entailed. When I invented the program and people showed up at my house for the first meeting of the CCL Fellows, I couldn’t believe that! That people had bought into this dream. Every year it sort of surprises me. I think it’s an amazing thing when you can affect the lives of other people.

You must go to bed feeling good every night, right?

I’m very moved by the impact CCL has on other people. It’s something I think about all the time. No, I go to bed every night worried about raising money for the program, but in better moments, then I’m very happy.

So how are you doing post-program?

I think a lot of people, including me, experienced a great sense of success, wonder, and sadness that it’s over because it is so intense. It felt so much like being back in graduate school when I learned many new things. But, I also learned all the things that I don’t know. That is a great and scary thing.

Yes, but isn’t that really the key in life: knowing what you don’t know? That’s exactly what I’ve always said.

It’s so important. It keeps you humble and it keeps you focused on learning.

And that’s what life’s about.