Aliza Shvarts

Aliza Shvarts was 22 years old when Yale Art School banned her performance art piece Untitled [Senior Thesis] (2008). The project, in which she used her body as a medium was met with international controversy, even resulted in death threats.

Today, the artist and scholar is completing a PhD at NYU, teaches at The New School, and is a Joan Tisch Teaching Fellow at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

impactmania sat down with Aliza in East Village, New York, where she looks back at the response to her senior performance art piece. We discuss the power others have over our bodies, belonging, and what we all have in common.

Aliza, how do you look back at the year 2008?

The year 2008 [financial crisis] was impactful for everyone. It’s interesting to see how we’re still living with the legacy of that on a global scale. A lot of my work is thinking about how these larger social forces, like the material conditions of capitalism, are felt personally — both through how we express ourselves as gendered subjects, and how we are able imagine what our bodies can do. This is how I see the feminist framework that I use: I bring together the persona and political through performance-based concepts such as endurance, duration, and legacy.

A lot of the looking back I’ve been doing on 2008 has been in anticipation revisiting my controversial work Untitled [Senior Thesis] next year. I’m having a solo show at a gallery called Artspace in New Haven in May 2018. I interned there at age 18 when I first got to Yale, so it’s a very friendly space to revisit, one where I feel very supported by amazing feminist curators. And by revisiting the work 10 years later, I’ve been able to have a lot of conversations with people who I didn’t have conversations with at the time.

What will you be revisiting?

Partly I’ll be revisiting the experience of having my work banned and being denounced by a major university at age 22, and partly the project itself, which was never fully realized because it got banned. Working with this nonprofit gallery, I’m getting a chance to more fully articulate aspects, I felt were left out of the conversation at the time, as well as show materials I never got the chance to show.

Will you bring the project to fruition with this new gallery?

I’m not re-performing it, though I will be showing some of the banned video footage. A big part of the piece was the context of its reception. That was always something I anticipated being part of the piece — though on a much smaller scale. I thought it would spark conversation on campus, but did not expect this international controversy. That reception will be inherently different 10 years later, so on some level revisiting the work will constitute a new work all together.

Since it became more about you versus the project, was the whole dialogue of the human body and art missed?

Yeah, I think so. I crafted a very particular set of acts, though most people don’t even know what those were, you know? There was this sound-bite version in the headlines, and it became the version that circulated, almost erasing what I actually did with my body. That has actually profoundly impacted my work since. I’ve been interested in ideas of gossip and rumor — how narrative circulates and has a performative force to it. That’s largely from this experience of being banned.

Do you understand why people were so upset with the project?

I do and I don’t. It’s interesting, ‘cause there is a range of things that people are upset about coming from very different political perspectives.

There have been other artists who have used blood in art.

Certainly, yeah.

And have treated the body as a medium in art.

This is an established tradition in feminist art since at least the 1970s. Yes.

Do you think people were disproportionately outraged with your work?

I don’t know — it’s hard to say because not that many artworks have dealt with biological reproduction and abortion. As a social and a political issue in the United States, it’s an overdetermined discourse. I think that’s why people didn’t really pay attention to the nuances of what I actually did. The suggestion of miscarriage, the suggestion of abortion, was enough to incite people’s already-instilled beliefs.

I did a lot of research before I did the piece. I was looking into all these medical journals and reading articles where doctors were advising other doctors on how miscarriage should be talked about when talking to the parents. There were all of these articles saying, “Well, you should let the mother decide how to address it —follow her emotional bond, whatever it is.” It was crazy to me that a doctor would need to be told this by an academic article — that women didn’t have the power to choose how they relate to the products of their own bodies, that doctors had to be officially advised in the twenty-first century simply to listen to women and to believe them.

I’d say this reading was a large inspiration for the project: it made me think about how the greater feminist act is not insisting on one of two pre-determined narratives of what counts as life or what doesn’t, but rather insisting on the right to choose in a more complex way. Insisting on the right to determine one’s own relationship to one’s bodily capacities. That was a large impetus for the piece, and if I really think about it, actually seemed to be the most contentious aspect.

![Film still from Untitled [Senior Thesis] (2008) and Official Statement from Yale University. Courtesy of the artist.](https://www.impactmania.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2_senior-thesis-still-879x1024.jpg)

Film still from Untitled [Senior Thesis] (2008) and Official Statement from Yale University. Courtesy of the artist.

I think people just have strong emotional associations of reproduction. It’s such an important part of people’s lives: whether to biologically reproduce or not to reproduce. The project was always about making that question more visible, more complex. A lot of women suffer from the predetermination of a singular narrative around reproduction. And they experience themselves as failures in relationship to it. That’s such a violent, painful thing that the larger social world imposes on women, especially when reproduction is not just a biological act. When we really think about what reproduction is, we have to acknowledge that we are reproducing ourselves, our families, and one another socially, emotionally, and politically all the time.

In the end we cannot even have a discussion about it.

Yes, the discourse is at such a fever pitch that there’s very little room to be able to say something more. Which is actually the purpose of art, right? Art often becomes a place to say things that you could not say in the political field. It’s a space of experimentation.

What has been a surprising learning experience for you as an artist?

At the time, I was very surprised about the strong anti-Semitic discourse that my project invoked. I kept getting all these death threats, a lot of very ugly emails, and a lot of them referred to me over and over again in this very particular phrase: “murdering Jewess.” I was interested in the peculiarity of that phrase. I remember wondering at the time, “How do they know?” I mean, I guess I read as pretty Jewish, but my ethnicity wasn’t part of the work.

I Googled around a bit curious about where this language was coming from and I found a neo-Nazi website in which there was a forum. There was an argument within the forum over the question of “orthodoxy.” The participants were obviously against abortion, against women’s choice, all of that. But another faction was making the argument that I was a Jewish woman killing my Jewish offspring and that they should support that as a matter of “orthodox” white supremacist belief. It was such a shocking debate to encounter—one that I couldn’t even have imagined beforehand. It was an interesting glimpse into the broad scope of ideology.

As we’re learning, particularly after the 2016 presidential elections, that spectrum is actually far broader than we anticipate in certain places.

Did you find any support at the time for your work?

I did have some people voicing their support at the time, though I didn’t really have that in a very public way. My friends and certain professors were there for me. But the university administration punished by either censoring or firing anyone who had provided any concrete or public form of support. The Dean of the Yale Arts School at the time, Rob Storr, actually prohibited the Yale arts faculty from giving me any type of critique on the piece, even though it was my senior thesis, because to do so would be to acknowledge it as art.

I now meet academics and artists who are interested in it though, especially younger generations of artists who’ve since read about it. Maybe this is why the idea of intergenerationality has been so important for me. In your own moment maybe you might find no context, but context unfolds over time.

How did you get so ballsy?

[Laughs.] It doesn’t occur to me often that I’m doing something ballsy. I’m used to pursuing thought or certain types of theoretical premises rigorously. They often bring me to places that are challenging.

But where is this passion coming from?

I think it just comes from my dorky belief in what the role of art is. There’s a lot of artwork out there that reaffirms a conventional idea of the aesthetic. That art should be beautiful, or it should be a nice commodity, it should look good above your sofa, all of that. We might all have our own opinions about that. But what excites me so much when I undertake a new project is that art is this very special place where you can experiment. You can delve deeper into those various forces, those very material conditions that determine us in our daily lives.

Art can be a place to rehearse things. Most of this comes from a critical sense of utopia — a desire for things to be different.

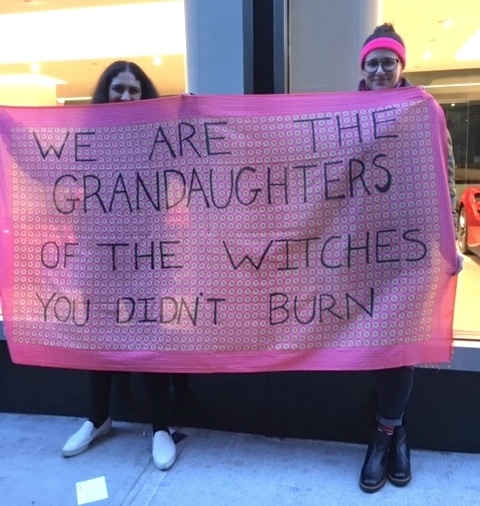

Aliza Shvarts with Trista Mallory at the 2017 NYC Women’s Day March.

What kind of things do you want to be different?

Things for women, things for queer people, things for people of color. It’s about refusing the present conditions. I mean, we all have to live, we all have to negotiate the present conditions as they are, but can do so with an eye towards something better. We have to make do but that doesn’t mean we have to accept that things couldn’t be different, that power couldn’t change over time. This is an idea that really comes from my PhD advisor at NYU, José Esteban Muñoz, after the project.

José passed away in 2014, which was very sad. It was very sudden. His last book was called Cruising Utopia: the Then and There of Queer Futurity (2009).

In it he posits an idea of queer utopianism. A lot of politics is about critiquing the present, unpacking these different ways in which power is violent and is impacting us in ways that we might even not know. But after a while, there’s certain exhaustion to that. But then where do you go, what do you do — how do you enact critique in meaningful ways?

His book was about not just how the future can be better, but how the future could be something that’s not already determined, how futurity itself is something that is made and enacted. His idea is that utopianism is a criticality of the present. It’s a queer orientation towards a horizon that’s not yet here.

It’s profound because it tells us that we don’t have to necessarily just be given to the impasses in the present, right? The battles we fight are not necessarily in the here and now. We can marshal all the resources available to us, not only in the present, but also across generations of people. I really like that.

And I realize I’ve gotten away from your question. [Laughs.]

How did José Esteban Muñoz leave an imprint on your professional career apart from influencing your current work?

Right out of Yale, I applied to a bunch of MFA and PhD programs. It was a difficult moment, because every single MFA program rejected me. I had some extra phone interviews with one program, in which one of the deans got on the line and asked if I was “sorry for what I did to Yale.”

There was a lot of anxiety at the art institutions about my practice, which was very painful. I felt that with this project I was articulating my practice within a feminist lineage — one that would connect me with other artists I respected and admired, many of whom were teaching at the art schools I applied to.

I felt from the art world an overwhelming silence, but thankfully that was not true from the theory world, Established artists weren’t necessarily interested in talking to me, but art historians were. Jennifer Doyle wrote about my project in relationship to work in her book called Hold it Against Me: Difficulty and Emotion in Contemporary Art (2013). She is actually the one who suggested that I go work with José. Meeting both of them, I felt taken up in a certain realm of queer theory and feminist art history. José lobbied pretty hard for me to come to NYU. I felt very wanted, like I had found a real community.

What has he said or done besides obviously looking at bringing you in to continue your work. Is there something he said that stays with you?

One thing he said which I’ve since stolen, ‘cause I think it’s a great quote, is the closest thing he does to a “sport” is “pick over the bones of old, dead, white men.” [Laughs.]

It is actually also quite a serious idea too, because it brings up the question of whether it is really possible to live in a world where you only encounter people who share your politics. How do you take the resources of the world as it is and use them for your own project, for your own flourishing?

Especially as a person who feels minoritized in different ways. His book, Cruising Utopia, proposes a really important model insofar as it heavily draws on the writings of Ernst Bloch, who was a Frankfurt School philosopher. Bloch would probably not be so happy that he was this major inspiration for queer theory. Many of the philosophers we use in contemporary theory are imperfect. They’re people too, right? Often they’re racist, homophobic, misogynist people with complex lives.

Have you found a way to work with thinking from others that is different from yours — how do you build solidarities through difference?

Solidarity must be possible beyond a realm of self-identical formation. Which is to say that solidarity has to be possible in a way that maintains rather than erases difference.

An extreme example is to take the work of thinkers who would be horrified by you and use it for your own thought. In a prior book, José had a term for this, which is disidentification. He raised this very important question, which is how do you identify or dis-identify with a larger formation of power and use that for your own flourishing?

I took a class with him called “queer belongings” — which was a concept I really didn’t get at first. For me, my queerness has always stemmed from my weirdo-ness. I’ve always felt at odds. I didn’t understand why I didn’t want what the other girls wanted. It was a very isolating experience growing up.

So I cornered José in the hallway, during one of the breaks and said: “José, I don’t understand — what is queer belonging? What does this mean?” He was trying to get rid of me, like wanted to go for coffee or something. [Laughs.] But he tried to calm me down. He said that it’s important to think about the lived paradox of belonging. Most of the great theorists of community, of collectivity, people like Karl Marx — they were these weird loners sitting in their rooms dreaming of a future collective, dreaming of the possibilities.

I think what he was telling me was that it’s not about a comfort in the present. It’s about this critical political commitment to go beyond the individual self. And perhaps the people who feel that desire most acutely are people who have felt isolated in their own individual selves. Now I’m much more interested in ideas of kinship, collectivity, and community. That was the turning point for me.

We’ve been interviewing architects, religious leaders, and economists about belonging. Belonging — what does that even mean? Is that a virtual space, a state of mind?

It’s a great question, because I think that technology changed us so much. Most of our encounters are mediated; you can have deep emotional commitments to your phone. Anyone that’s ever dated long distance feels the romance of that technological interface. [Laughs.]

You touch on something here, with virtual reality, now your brain thinks it happened. Is it then real?

Yes, is it real? Is that difference even meaningful? It’s a fascinating question.

On some level, we’re getting more and more able to overcome the ways we are physically apart. I think this is especially important for women, as there are a lot of patriarchal structures — historically and in the present — that conspire to keep us apart. For example, if you’re the feminist on a panel, there’s only one of you, right? It’s similar to how if you’re the person of color at a panel, there’s also usually only one of you. There’s this way in which you don’t get to feel your collectivity because you’re a marginal in relation to a majority.

People manifest their own collectivities in such different ways. I believe in the ways in which, for example, the girls on Tumblr are engaged in a collective project. Feminism can unfold in these virtual spaces too. Those types of collectivities are just as meaningful as people gathering in the streets. It is just as meaningful as a consciousness-raising group would’ve been in the 1970s. There’s this great power in coming together, even if only briefly, that people are manifesting for themselves with the tools they have available. Especially now, people are really invested in organizing resistance to the current administration.

You teach a number of classes, from feminist art to critical thinking. What is the most difficult thing for students to grasp?

My classes are fairly political and fairly radical, so the students who take my classes are pretty self-selecting. We begin with Marxist theory and we only get more critical from there. There’s an exuberant moment where they’re embracing the criticality — learning how violent capitalism is, how it’s imbricated in all of these other structures of racism, sexism, colonialism, and genocidal violence.

It can be hard for the students though, because you are teaching about ideology as a historical construction and violent formation, and at the same time, you’re teaching that there’s no outside to ideology. We’re in it. That’s always an interesting moment for me to listen to the students, to try and engage their questions about how we can work towards a nonviolent future. The answer I have for myself, the answer I give them when they ask me what we can do in this system, is that theory and art practice are amazing spaces where you can envision the future. This is a place to rehearse and to stage resistance.

Of course, I try and resist this cathartic trajectory of a single progress narrative — how through art, you arrive at utopia. You never arrive at utopia. Utopianism is itself what you do with your criticality. That’s the hardest part for students. It’s overwhelming to learn about how, for example, the wealth of the United States is very much based on the expropriated lives of enslaved people, brought here during the transatlantic slave trade and the genocide of indigenous people. They want to know what the right thing to do next is, but there is no right thing. Just provisional solutions.

Our own history as a nation involves the most violent forms of atrocity. It’s traumatizing for students to hear about and to feel their own implication, or to suddenly have a historical context in which to situate their own individual experiences. But that’s also what’s transformative about learning, right? From that place of trauma, they necessarily have to rebuild. From that place of individual experience, they come to collective consciousness. And I think that process is valuable for them. For all of us, really.

You spoke of minoritized people who need to work within the capital structures. How is this for artists who may be working outside of the structures but their artwork would still need to be supported by museums and collectors?

You can see directly how things are stacked against artists. It’s the people in charge of major institutions, directly profiting off of an endemic system of debt in which most artists are entangled. Even if you can sell your work and make a profit, you’re still in that debt cycle.

Occupy Museums has a piece about this in the current Whitney Biennial. It’s a very clear legible piece, it is modeled on the idea of an art fair but instead of just the art on display, the debt of the artist is also on display.

They curated 30 works which are “bundled” into the types of debt that the artists hold. Some of them are student loan debt; some of them are credit card debt; some of them are debts related to the Puerto Rican debt crisis. And then, interwoven into the piece are references to BlackRock, which is the largest asset management company in the world. At the top of the installation is a quote from the CEO of BlackRock, Larry Fink, in which he says, “The two greatest stores of wealth internationally today are contemporary art and apartments in Manhattan…”

That gives you this glimpse into the logic of the collecting class.

The most powerful part of the piece though, at least for me, is what you see underneath Fink’s name. You see that he’s the co-founder and CEO of BlackRock, Inc. And that he’s a trustee of MOMA, trustee at NYU, and a major beneficiary of the 2008 financial crash. [From the Occupy Museum website: “Blackrock Inc…it barely existed before 2008. Today it manages 5.1 trillion dollars of assets. If you hold any kind of debt to any bank, chances are that it is traded by Blackrock. The firm is deeply invested in Americans—and especially students to remain in permanent debt.”]

This is where my socialism comes out. What does it even mean to accumulate wealth? We all believe in hard work. Wealth is hours of someone’s life. For wealth to accrue, someone else has to be selling his or her labor time at a loss.

Art has become such a luxury commodity and also a store of wealth. A lot of people park their money in art because it’s fairly compact, and it’s going to appreciate in value. It’s a larger system of speculation that artists themselves don’t benefit from — one that actually necessitates that artists are under-compensated for their labor.

It’s what you mentioned before; you are part of the system that you can’t escape.

Yes, and this is why some artists build ways in which their works get sold. To limit the potential for speculation on their work, if that’s possible.

W.A.G.E, Working Artists for the Greater Economy, has done amazing work about insisting the artists being recognized for their labor and remunerated for it. So many artists are told that they should do things for free, because it’s great exposure.

You can die of exposure. [Laughs.] When our labor goes unpaid, we’re told that we’re supposed to recuperate that in the objects that we sell. So the objects have value, but we don’t, our lives don’t. This is a trap. Everybody’s life should have value. It’s a system that ignored what artists really do — as if our labor itself wasn’t what produced the value.

Some of the innovators and economists I interviewed say, “The artists are the ones who will escape the robotizing of work.” The artists has the ability to create — a skill that can’t be easily taken over by robots.

That is interesting. On some level, it totally makes sense that artists and the creative class will be the last vestige of human originality. Which goes back to a romantic model of what art was, where the artist has this interior that they bring to the world via their objects. Kant calls it the “genius” of the artist.

Then there is this social model of what artists do, which is we see the conditions that we share in a social world and try to intervene in them. In this way art is less about genius and more about experimentation and revolution. And art affords that, right? The studio offers you a space to do the things you couldn’t do on the factory floor or in the office.

Of course, the studio, the factory, and the office are all sites of production for commodities and wealth. But if artists are willing to intervene critically in present conditions of value, maybe they are still doing something original that automated labor can’t fulfill.

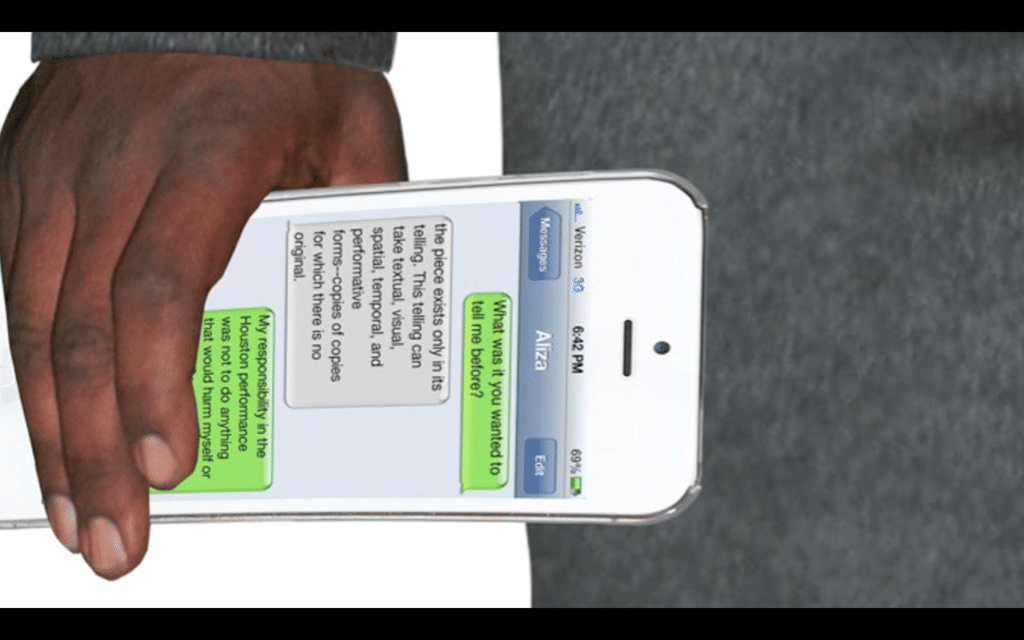

Film still from Nonconsensual Collaborations (2012-present). Courtesy of the artist.

Give me a few words that describe your journey so far.

Well, that is a hard question.

The phrase I’ve been thinking about a lot, which connects my Untitled [Senior Thesis] piece to my ongoing Nonconsensual Collaborations project to this “viral” turn that I’ve taken in a new digital piece called How does it feel to be a fiction? is this idea of wayward reproduction.

Part of the difficulty of being a queer subject is that you feel the means of reproduction — physically but also socially— are not yours. There’s a feeling of incapacity. But there are so many different ways that we can reproduce ourselves, ones that don’t depend on these structures of power.

Biologically there’s a lot of ways to have children, to pool your reproductive capacities, if that’s what you want. I don’t have children and I don’t want to have children, so something more meaningful for me is this idea that we can also socially reproduce each other in a lot of different ways. We can collectively reproduce each other in ways that are not necessarily within these channels of what’s allowed. That for me is what art is, it is what teaching is, and it’s what friendship is. I think that’s what writing is too.

It’s this way of being part of something without having to be part of it in the way that’s prescribed. I’d say that’s a big motivating factor in my work: I’m always exploring how to reproduce an idea, how to reproduce a politics, how to reproduce solidarity or community outside the traditional realms of visibility and action.

You mentioned that you felt like a weirdo — don’t you think that everybody feels that way?

I do! There’s this illusion that if you want to be part of something, your belonging has to be based on similarity. But solidarity is not necessarily about similarity—it can also be about differences that cannot be resolved.

José used in his work this idea of “identity-in-difference.” It’s a phrase coined by Latina Studies scholar Norma Alarcon and is used in LatinX activism. That’s this idea that the most political thing to hold in common is exactly that idea of difference.

Everybody feels different, but I think everybody feels difference differently, right? The difference you might feel internally while being rewarded monetarily in your life choices has different stakes attached to it than when your difference authorizes violence against you.

But ultimately, yes — I think difference is what we have in common.