Dr. Laura Jana speaking at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce on the importance of high-quality childcare and early education.

Dr. Laura Jana, pediatrician, former Director of Innovation at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, and award-winning parenting and children’s book author, was approached by Reid Hoffman to review his book, The Startup of You. Laura realized that Hoffman’s observations of what it takes to be successful were similar to the advice she gave to parents on childrearing. She spoke with impactmania about how to prepare our children for the future and shares one of her own parenting fails.

BY PAKSY PLACKIS-CHENG

How good was [LinkedIn’s co-founder] Reid Hoffman’s book The Startup of You?

It was good on many levels. The Startup of You has an intriguing concept. Today, people are shifting the way we look at ourselves, what we stand to accomplish, and how we approach it.

I was intrigued by this idea of treating yourself like a startup. Reid Hoffman’s observations about what would help people be successful were almost word for word the same as what I talked about as a pediatrician with parents. When Reid asked, “I’d love to know what you think of the book.” My first reaction was, does he really want to know what I think of the book, or is he just being nice? [Laughs.] But what I said was, “I think it reads like a parenting book.” I’m pretty sure he’s never gotten feedback like that before.

When I explaining to him how there is this crossover relevance to what’s happening in the world of early-brain and child-development, parenting, and education, his response was, “This is a killer idea.” That’s what set me on the course of an unlikely professional path. It was reinforcing to have someone at Reid’s level in a completely different space to see what I was seeing. I told my husband, “You see, I’m not crazy!” [Laughs.]

There’s so much talk about the jobs children are going to have tomorrow that do not exist today, that education is broken, and we are defining success in very narrow terms. How should we prepare our children?

You make a good point. I am not presuming to define other people’s sense of success. And yes, about 65 percent of kids today are estimated to work in jobs that don’t currently exist. That gets people’s attention, but even by definition, we’re talking about jobs as if what job you hold defines your life. I think of success as being a good person, kind, motivated, contributing to society. Again, I leave it very general, because even when I was a practicing pediatrician, I didn’t presume to tell parents what their definition of success should be.

As a pediatrician, isn’t it part of your mission to be an advocate for children? Financial success matters to health, but hopefully one also finds success in the terms of mental stability and having positive social relationships. Do we need to help parents understand that those are also measures of success?

Yes, yes, you are absolutely correct. We hear about robots taking over our jobs, what do kids need to do to succeed? There has been a push toward skills in a very literal sense — the reading, writing, arithmetic, and technical skills. Some of the research articles say the problem is that we’re too focused on skills. What I’m actually talking about are abilities.

I was really good at memorizing facts when I was in medical school. It made me look really smart, right? I majored in cellular molecular biology — with lots of details to memorize. The person who could memorize the most seemed the smartest. In this day and age, just having the answer doesn’t get you that far, because anyone with a smart phone can get the same answer. You have to know how to filter through the information.

You have to realize that the world has shifted, which we hear about in general terms, but not so much in parenting terms. Everybody’s shifting their focus to the ability to ask good questions, instead of having the right answer. We have shifted to being able to fail, adapt, and then accomplish something. The question is, how do we help kids develop those abilities, so that they can face whatever comes.

It’s also the recognition that neuroscience caught up with early childhood and parenting. I’ve always thought that early childhood was really important. Talking and cooing and singing and reading books to babies are really important things to do. Neuroscience now tells us right down to the level of connecting neurons in the developing brain that those are good things to do. I think a lot of people have taken for granted. It’s almost like we pay lip service to ‘Yes, the children are our future and that this is why we do all of the things we do,’ but that doesn’t always play out in our actions and priorities. In my case, advocating for children and funding our policies.

Speaking of lip service: How do we work toward a more appropriate education system? It doesn’t seem that we are focusing our resources to support a system that is preparing our children for their future.

We look at these huge sets of skills, which I call QI skills (or Chi).

I incorporated all of what people are talking about and are familiar with: emotional intelligence, life skills, grit, perseverance, resilience. When you look at my framework, which is the, ‘Me, We, Why, Will, Wiggle, Wobble, and What if’ skills and you start looking around, you actually do see the educational system shifting in that direction. Mindfulness practices being done in classrooms to get kids to focus and pay attention before they start the day. Or this flip-the-classroom and have more discussion and interaction and collaborative work where the reading is done outside of class.

So how do we develop more appropriate educational system? We’ve done such a good job of silo-ing health and education, right? As a pediatrician, people often wonder what I’m doing in the education system. I owned an educational child care center for ten years; I talk a lot with educators. To me, when you start with a child focus, you can’t separate education and health. What I’m seeing now is, especially in this realm of QI skills or social/emotional skill development and executive function skill development, it is at the heart of the conversations going on in both the health system — in pediatrics, psychology, psychiatry, social sciences — and in the education system.

I’m surprised that you’re so optimistic about our education system.

I see it being very positive, because it is shifting toward things such as empathy and teamwork and collaboration. This makes us human and defines my view of success.

Further commenting on the educational system, not only do I see it needing to be reunited with all of the above-mentioned areas, but early childhood education has never been fully validated as part of the educational system. It has historically been seen as babysitting. It was great if you just kept a kid from getting hurt. You fed them, bathed them, put them to sleep, right?

Dr. Laura Jana visiting a crèche in Dunoon Township outside of CapeTown, South Africa.

Tell me a bit about your board role at Owlet, a smart sock that serves as a baby monitor; how are you bringing the importance of early childhood education into companies?

I’m passionate about maximizing children’s potential. If you care about children, you care about families, right? Then if you care about families, you talk about communities. If I’m going to impact outcomes for children, I need to be working in a whole lot of areas beyond just being child focused. Based on all of what’s coming out in early child development literature, a caring responsive adult is perhaps the single most important factor in child outcomes, right? It’s not rocket science, or as I put it, it is neuroscience.

If we know that there is a lot of foundational development that takes place in the first five years, including these 21st century skill developments, all of which is dependent on a caring responsive adult. What does that mean for children who don’t have that?

I predominantly work with companies focused on the juvenile space. I look at the work I do as if I’m hijacking companies’ marketing arms and inserting practical and relevant information for parents. To make sure that what’s going out from these powerful marketing arms serves a bigger purpose. I also do things on a community level, I look at providing technology access to underserved communities, whether that’s early-literacy or health promotion.

You mentioned an adult’s impact on children. I’ve been interviewing young women, in countries like Pakistan. When I asked these women how they were able to have such a strong voice in a society where that is not appreciated, they credit a family member, usually their father, for their success in life. How do we encourage, especially fathers, brothers, men to be better supporters and be more involved with their children, especially their girls in countries like these?

I had the chance to visit Harvard’s Center on Developing Child where a lot of cross-collaborative research is being done. We can predict children’s outcomes based almost entirely by the zip code that they’re born in. Somebody always points out an example of someone who’s faced adversity, hasn’t had the community support, comes from a repressive, abusive, or neglected environment. My question at the Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child was: What is it that makes kids get off their dismal life trajectory? The answer was a caring, responsive adult. This is based on parsing out all the literature and the research.

That was so striking to me, especially when you combine it with the brain science that shows children who hear more words and more positive words of encouragement, you can see different patterns in the way that their neurons connect in the developing brain. We can visualize this now; we can see it happening.

When I think about what can we do, I don’t presume to define the family unit, it’s a caring, responsive adult whoever that might be. What does that do to your worldview when you hear people talking about coaches, teachers, and clergy?

How do we ensure that all children have the opportunity to maximize their potential? That gets to the core of what I’m interested in. If a child spends 12 hours a day in the care of someone other than a caring, responsive parent, we need to care about those interactions. Sometimes it’s not even the quantity of interaction, it is the sense that someone believes in you, and supports what you’re doing. I’d love to spend my life finding those people who do that, and then ask, “How do we do that for more children?”

Dr. Laura Jana visiting preschoolers at the Global Discovery School in Nashik, India.

Your work is focused on early childhood, but there has been so much news around the teenage years and anxiety, even suicide and shootings. How do we, parents, coaches, educators, help counter stress and trouble in a teen’s life?

If you look at the framework of the QI skills, the 21st century skill development norm, it is the entire continuum, from birth onward. I have focused more time on early brain and child development, in particular, because to me it was the forgotten window of opportunity. Even in education, when people start talking about reform, it is about STEM education in middle school and K-12 education. I kept thinking, wait a minute, zero-to-five [years] need to be part of that conversation.

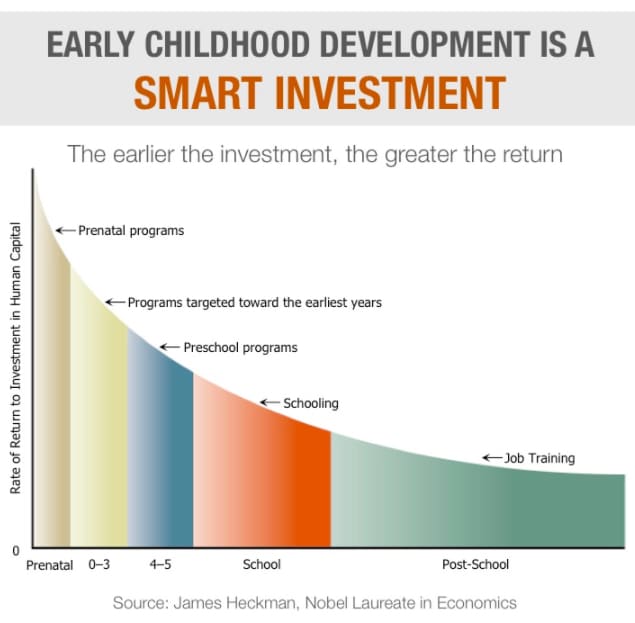

The Noble Prize winning economist James Heckman puts together useful info-graphics about investing in early childhood. He has provided so much information and research on the economics of investing early, which is really important when you’re advocating for policies and programs.

The Heckman Curve, courtesy of The Heckman Equation Organization.

I pay a lot of attention to what’s happening with teens and stress. Part of that ties back to the brain science. We know there are two parts of the brain that sort of counter each other. One is where the executive function skills take place. They are the skills that make you stop and think through your actions. It’s cognitive flexibility, working memory, and impulse control. That last one always gets people’s attention. That is why two year olds bite and five year olds shouldn’t. Because there’s the most rapid rate of development of executive function skills between the age of three and five. Two year olds don’t have a lot of it and five year olds should have more. But the next part of that sentence is always: Don’t give up on older kids [if they don’t have great impulse control yet].

I have two kids in college, and one in high school. I always say, “Don’t give up on them right during the teen years,” because we know that executive function skills don’t fully develop until the 20s.

In the teenage years, that part of the brain, the prefrontal cortex, that’s supposed to make you stop and think through your actions, weigh your options, and consider outcomes, isn’t as strong as the other part of the brain, the amygdala, controls our fight or flight, impulsive behavioral response. It makes perfect sense that we have that part of the brain. Because, if a saber tooth tiger was chasing you, it does not serve your best interest to stop and think through, I wonder how hungry he is; did he already eat lunch today; is there someone behind me who he could catch before he catches me, because then I don’t need to run so fast. Rather, it is best to jump into gear and just go.

In the teenage years, the neuroscience tells us that those two competing brain functions are a little out of whack, right? You’ve got more of those impulsive behaviors, and less of those executive function skills putting on the brakes.

What have you learned when your children went through teenage years?

One of the things that was striking to me when my kids hit teenage years, especially my boys, was that the minute that they shot up taller than me and their voice dropped down so low that they sounded like my husband, I needed to remind myself that they were not at the same cognitive level as an adult.

They sounded like an adult, they looked like one, but we need to remind ourselves that teenagers are still figuring out their identity. They’ve got lots going on, not just with their hormones, but with their brain and how they regulate their behaviors. And now, they are part of a massive experiment of what happens with technology and the stress of education.

What’s tough — as optimistic as I am — is figuring out what we need to do to make these shifts in both the health care and the education systems.

We can encourage kids all we want — communication, cooperation, teamwork, ability to fail and adapt, but until that massive system shifts happens —so that the gatekeepers to college look at something other than at IQ skills and our standardized test scores— we can talk until we’re blue in the face about how to perform these other skills…if that’s not the hoop that children have to jump through to the get to the next level, they’re going to feel that stress.

So what do parents do? Any tools?

Parents are really influential, even when they’re having the teen challenging behaviors, right? Parents provide teens with a compass and a sense of stability and security and consistency is really important, even when they get pushback.

One of my three kids gave me a lot of pushback during the teen years. It was really frustrating, because I kept thinking; I had this great relationship — what happened? We got past those couple of years. In retrospect, by being able to provide a consistent approach and expectations, even though there was pushback, was valuable. The other thing, though, for parents is to recognize when they’re unintentionally or intentionally putting a lot of pressure on children.

Give me an example of how parents put unintentional pressure on children?

A good example of the unintentional is how parents describe their children to other people. If the first thing you lead with is their scores on their SATs, their GPA, their class rank, you minimize accomplishments which the real world is starting to recognize are really important. Whether that’s somebody really good with empathy or it could relate with Will Skills — persistence.

Even knowing what I know, I will tell you that one of my kids had perfect SAT scores. If SATs don’t predict future life outcomes, and they certainly don’t predict success in the way that I define success, why is it that I was still really proud when a perfect score came in? Parents should really think about it. It’s similar to the discussion around gender. There’s the unfortunate tendency to buy girls pink and buy boys blue. When you need help in the kitchen and you call your daughter, and when you need help with a math problem you call your son. We are setting that framework, right?

That is where I caution parents, they can be very supportive and influential in terms of their own challenges interacting with their children or their children facing other challenges.

It is those subtle things that we may do that we may not realize are putting unnecessary and very negative pressure on children.

Since community at large will be stronger if we all do well. How can we get to a place where parents see children less as competitors and encourage parents to become better supporters of other parents?

Yeah, that’s a really good question and a tough one. First of all, I can’t tell you how many conferences I’ve been to recently that are much more on the innovation business side of things, where people are saying, “It’s not a zero sum game,” and that collaboration actually gets you better outcomes than competition. The argument that the world is becoming much more complex, one of us isn’t going to be able to solve all the world’s problems.

We need to be able to collaborate and we need to be able to collaborate across cultures and geography.

In terms of parenting culture, the competition comes with our parenting insecurities where we look like we’ve got it all figured out. I make a point of telling people, “I messed that one up also.” As a pediatrician I would say, “I don’t presume to have all the answers.” Even though I was trained 20 years ago when it was still much more like, I’m the doctor and I have the answer for you.

Once we shift that mentality for parents, you’re partnering with other people. You don’t have to have all the answers. Quite honestly, people relate to you better when you don’t pretend like you have everything figured out. If I have to look at one more Facebook feed about how perfect everybody else’s families are… I post parenting fails. [Laughs.]

What is one of your parenting fail?

As a pediatrician who writes books such as Food Fights published by the American Academy of Pediatrics, I was dropping my son off at college and we went shopping. He really wanted to buy instant Ramen noodles. I am dumbfounded by just how unhealthy they are —saturated fat, salt, lack of nutritional value. My son really wanted them. I thought, he’s about to live on his own, so I say, “Fine, you can have a couple of them,” even though I’ve spent years trying to help parents getting their kids to have healthier eating habits. I go to pick him up towards the end of the semester. I’m proud he’s cleaned his room — stuff that he didn’t do at home. Then I see all of these bags of ramen in the bin. I said, “You didn’t eat any of these.” He responded, “I had didn’t know how to make them.”

I was speechless for a minute.

“You boil water.” He said, “I didn’t have a way of doing that.” I was thinking, my son doesn’t know how to boil water! Where is the problem solving? I said, “Remember, we got you the glass measuring cup, you put water in it and stick it in a microwave?” And he responded, “Yeah, but it says, boil it in a pot.”

Knowing all I know about parenting and brain development, I’m hanging in there; he hasn’t reached the mid-20s yet — when his executive function skills are due to really kick in!

Well, he didn’t end up eating the bad noodles, so you got what you wanted!

There you go, that is looking on the bright side. [Laughs.]