Asian Cultural Council’s Miho Walsh on the Business of Cultural Exchange

Miho Walsh, ACC’s Executive Director. Photo by James Ware Billett.

BY PAKSY PLACKIS-CHENG

The Asian Cultural Council (ACC) advances international dialogue, understanding, and respect through cultural exchanges that nurture the talents of individual artists and scholars in Asia and the United States.

In 1963, John D. Rockefeller 3rd, established the Asian Cultural Council Program of the JDR 3rd Fund. Ever since its inception, the ACC has operated a grant program designed to deepen cultural engagement by combining funding with customized programmatic support.

Miho Walsh, executive director of ACC, spoke with impactmania about her role at the organization, the root of conflict, and what fuels social impact.

Tell me a bit about the responsibilities of serving as the executive director of ACC.

I started at the ACC in 2009 as the associate director, and have been the executive director since January 2013. It’s a big job in a small organization. We are headquartered in New York with offices in Tokyo, Hong Kong, Taipei, and Manila. Plus, ACC has nearly 4,000 alumni around the world.

What excites me is activating that community, creating connections between our alumni and our community-at-large so we can learn how to create better impact, more cultural exchange, and more understanding together. It’s the dream job for me for sure.

What have you been surprised to learn?

People travel all over the world today. There’s information about different countries on websites and social media. What has been surprising is how deep of a connection you can actually make, and the understanding and awareness that you can uncover about yourself when you travel or have a cultural exchange experience.

I was born in the United States, but grew up in Japan. All my life, I have traveled between Asia and the U.S. In my mind, I was coming into something that I knew. But I don’t think I truly realized how profound cultural exchange could be until I started running an organization that was committed to it.

Could you give me an example?

I traveled to Korea last fall, where we have many alumni. We gave an award to the president of the Seoul Institute of the Arts, Duk-Hyung Yoo. He was an early grantee back in the 1960s — a theater director who created the first avant-garde, contemporary theater in Seoul, Korea. Almost 50 years later, he is the president of a university with 3,000 students and thousands of alumni.

Before I visited him, I thought, well, I know a lot about Korea. I’d visited there before and had an understanding of its cultural history and modern cultural landscape. But sitting down and speaking with him, learning about what they’re doing at the Seoul Institute of the Arts in terms of technology and art, as well as their interchange with other countries in an arts-education space — it really was powerful. I learned so much more about the possibilities for cultural exchange.

Duk-Hyung Yoo, President of Seoul Institute of the Arts.

Anything in particular he said that stayed with you?

He said that his lifelong experience as an artist and arts educator has given him the chance to continue to hope and dream. It was affirming for me. I’m a deep believer in cultural exchange. The power of the arts, or the power of discovery and finding commonality through cultural exchange, is that it can be a completely transformative experience. So, when someone tells you about their lifelong commitment to pursuing their dreams, and you see the ripple effect that one person can have, it’s really moving.

In the 1960s, ACC funded Duk-Hyung Yoo to come from Korea to spend time in New York and Texas. He was exposed to the contemporary world of theater in the United States and took that back to Korea. Now, that one individual’s experience continues to have this enormous, continued multifaceted impact.

In the field of nonprofit, we often talk about impact or we talk about movements of social change. But when you boil that narrative down and distill it to one person — the action, experience, and commitment of one person, it can be extraordinarily powerful.

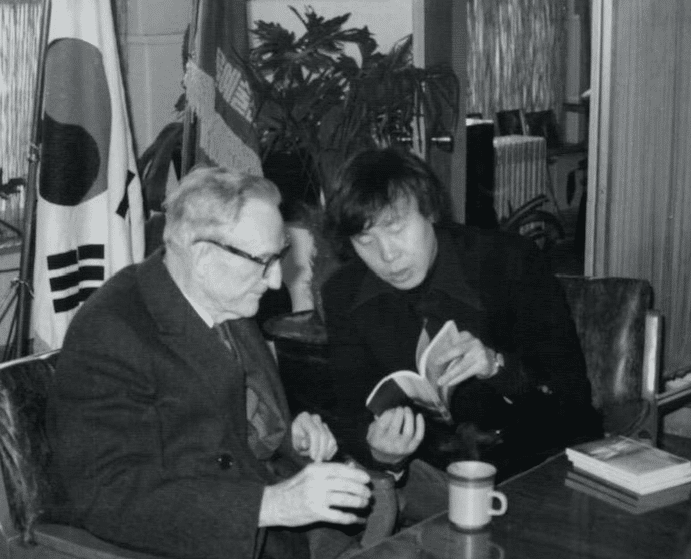

ACC Founder John D. Rockefeller 3rd with Duk-Hyung Yoo, President of the Seoul Institute of the Arts, in 1976, in Seoul, Korea.

With your experiences in the field, what are some of the ingredients for social impact?

On a surface level, you need the resources to make change. But more importantly and more deeply, you need to have a commitment to the values of social impact.

You have to be deeply dedicated to your cause and willing to try new things. You have to think, “I want to see this change. It is so needed in the world. We’re going to partner with people for it, and we’re going to constantly build on what we’ve done.”

The social impact that is at the core of ACC is this idea of promoting understanding in the world. Our founder believed that the arts were the best tool to do this — to empower individual artists with the ability to discover another culture. Then also to absorb aspects of that culture and to bring it back to their home community and share it…There are these two sides of the coin, understanding about the “other” and understanding about yourself, that would bring about this idea of a common humanity.

Our founder always talked about “… bequeathing a gentler world.” We often ask ourselves, what is a gentler world? What is a more peaceful world? How do we get there? There are so many things that tear us apart today in the world. The root of so much conflict in the world is a fear of difference. Disrespect happens when you don’t understand something.

At ACC, we think in terms of creating a constant international dialogue, communication, respect, and promoting a sense of mutual understanding and commonality. But our work is often hard to quantify.

You’re not handing out 10,000 meals…

Right, we don’t have bar graphs that show how many mosquito nets we sent to a certain community. The kind of impact that we’re seeing at ACC is much more of a long-term outcome.

It is about a changed mindset…

Yes, how do you accurately measure that? How do you talk about that? Can you say, “If this artist or this cultural specialist didn’t exist, what could have happened?” It’s hard to say for certain.

What is certain is that we are making change one person at a time, and creating these deeply transformational experiences. The connections ultimately have the outcome of an interdependent community committed to understanding and respecting each other more.

From that, many things can happen: innovation, problem solving, and cooperation.

Miho Walsh (seated center) and ACC staff from New York, Hong Kong, Manila, Taipei, and Tokyo. Photo by Pingkan Lucas.

There are some countries in Asia that would benefit enormously from more dialogue. I’m thinking of Pakistan, for example. ACC does not have an office there — how was the decision made on where to focus?

That’s a really great question, because we have had the same geographic purview for many years. We give grants to support exchanges that happen between people — from Afghanistan through Japan and south to Indonesia. John D. Rockefeller 3rd, who founded ACC, had a love and passion for Asian arts and culture, in particular Japan. He was sent as a special envoy to John Foster Dulles to look at the role of culture in and the rebuilding of Japan after World War II.

When you’re in the business of cultural exchange, and looking at the needs in the world, and what kind of role Asia plays in the world — which is a critical one — there are places that we would love to do much more in.

We have grantees from over 25 different countries. There are conflicts all over Asia that are happening on a day-to-day basis, whether they make the American press or not. I even look at the disputes that are happening in the contested waters between China, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Japan. There is so much challenge and disrespect.

Does ACC pair grant proposals with pressing issues happening in certain countries?

I would say that our strategy is to be responsive, but in an informed and strategic way. We deal with so many countries and so many different artistic fields — we support artists in 16 different fields. So do we support the arts administrator that is working in China, or the dancer that is working in Pakistan, or the conservationist that’s working in Afghanistan? It is a very hard decision to make because the caliber of our applicants is so high.

Every year we have a hard time selecting our grantees. We do look at the areas in which ACC can be specifically helpful or responsive to a need because of the alumni and the expertise that we have.

One interesting example is the field of contemporary visual arts in China. It’s a huge market now, and there are many visual artists that are commercially driven. For ACC’s purposes, we are not looking for the most successful visual artist or the next big commercial success in China. What we are much more interested in is the arts administrator who is going to be the programmatic soul of an institution or a museum.

Another example is the field of traditional music, which is important throughout Asia. We look to help artists working with traditional instruments in traditional Asian music find new avenues of creativity or ways in which they can preserve the tradition, but also ensure that it thrives within a constantly modernizing community.

We always ask our interviewees who has left an imprint on their professional DNA. I am sure that many people have supported you in making you the executive director that you are today. If you would have to pick a couple examples…

Three people come instantly to my mind. My former boss at Columbia University, professor emerita Barbara Ruch.

I worked at Columbia for many years, running what was called the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies. She also founded another organization called the Donald Keene Center of Japanese Culture.

She stands out, because to this day, she is fiercely committed to the idea of the importance of culture. That sheer commitment and determination is something that is very inspiring: the idea of constantly persevering.

Anything that she said that stayed with you?

My goodness, yes. [Laughs.] She said, “You have to identify the failure. Do everything you can to turn it into a success.” That approach was a powerful way of looking at things. It was coming from a place of really wanting to problem solve. There are a lot of problems in the world today that we can solve; being aware of what they are is the first step.

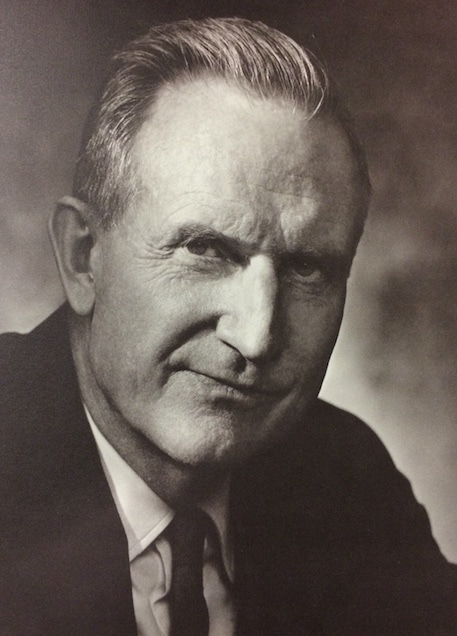

John D. Rockefeller 3rd, Founder, JDR 3rd Fund — precursor to the Asian Cultural Council.

John D. Rockefeller 3rd also is a constant source of inspiration. I didn’t know him. He passed away suddenly in a car crash in 1978. Yet his imprint on the Asian Cultural Council and his vision for what the philanthropic sector can do is incredibly inspiring.

He said, “The fostering of cultural relations can be a form of insurance for the future of this dangerous but exciting world…” And he believed in the power of the individual…When we talk about impact — the need to do so much can overwhelm us. What can one person do? He really believed that one person could make a difference.

In my mind, individual artist’s and cultural specialist’s day-to-day practices can make a difference in the world —whether it’s opening eyes, creating new ideas, or creating work that bridges divides. These individuals have a huge impact on me. They fuel the idea that culture can play an important tool in resolving conflict and in creating better understanding in the world — that mutual respect is what is going to save this world.

Miho Walsh in her office, New York, NY. Photo by impactmania.

Lastly, I am both motivated and inspired by my mom. She was a career woman but had a balanced work-life approach to things. She always wants the best for everybody. It comes from this indescribable love she has for her family, a love of learning, a love of wanting to make positive change.

In closing, give me one simple step that people can take in their everyday lives to make a difference.

Bigger than ACC, bigger than all of our incredible and extraordinary artists that are practicing their work every day to make a difference — is to have an open mind.

I really think that if you have an open mind and a curiosity about differences, you can become an important bridge in the world, not just a bridge from one point to another point, but a connector.