Lessons from Nobel Laureates

BY LEAH KURITZKY

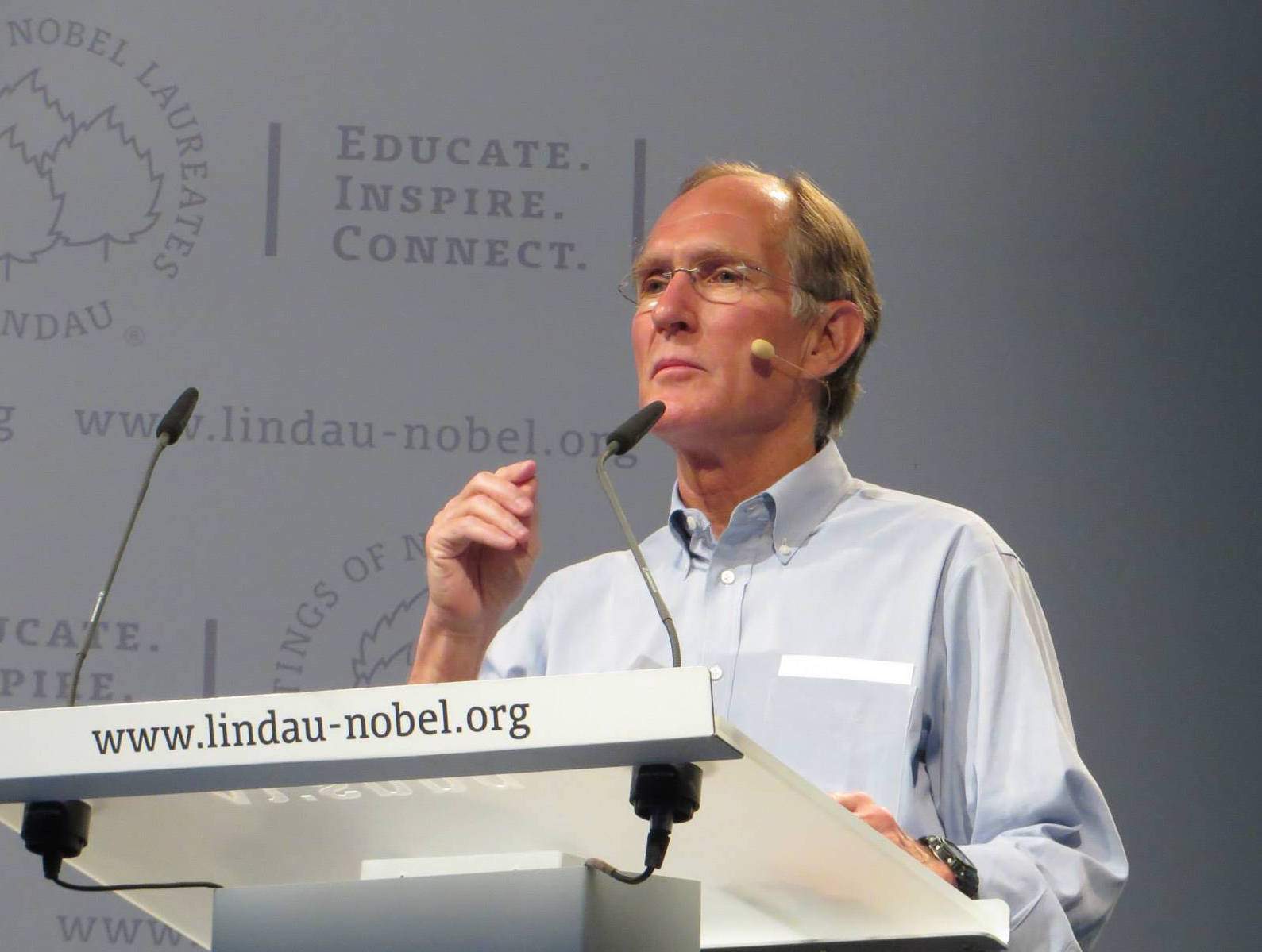

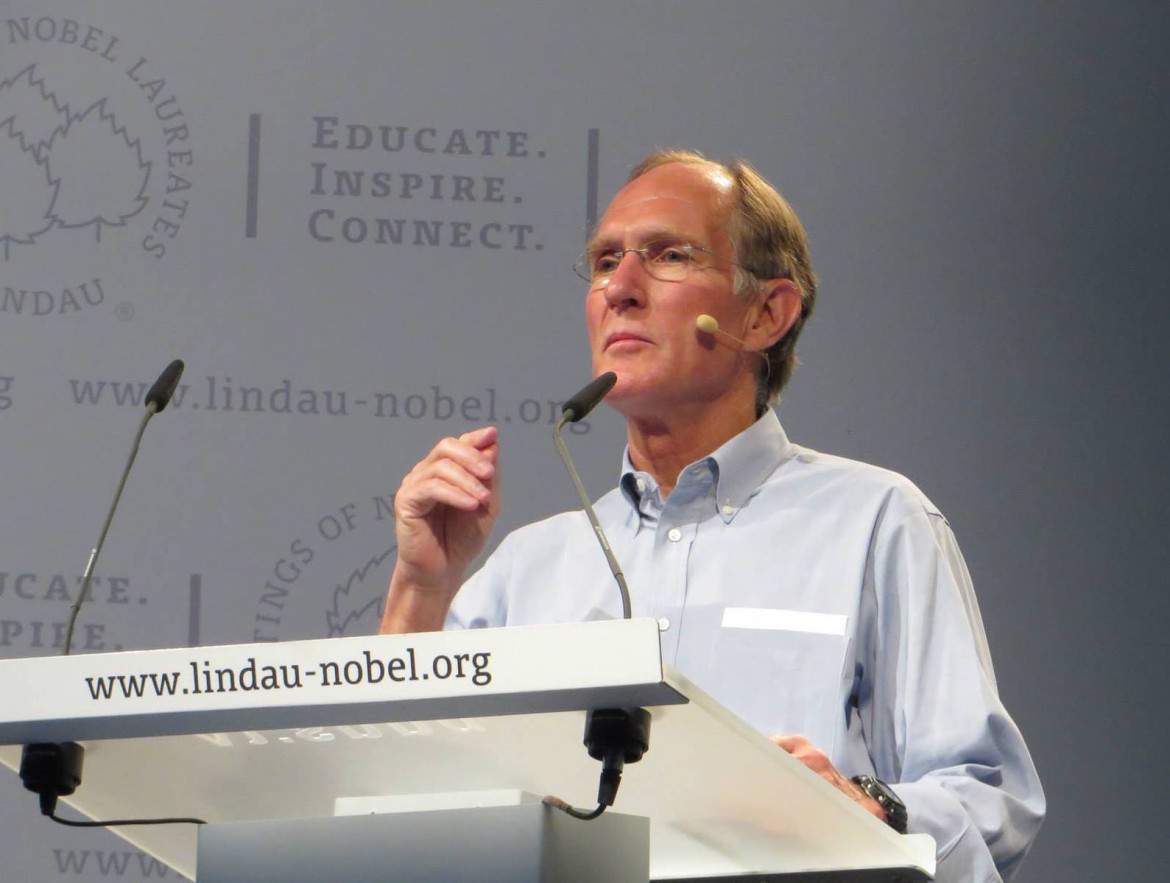

“If you don’t find intense joy from discoveries, even small discoveries, then you are in the wrong business, because this is currency we work for.”

– Peter Agre (photo)“Contrary to popular belief, I do not go under my desk each morning and adjust the dials that control the price of gas.”

– Steven Chu“I thought nature is at least as clever as I am…probably more.”

– Ada Yonath“You can believe in yourself when you have 2 things: You have to know a lot about everything in science; you have to know the basics. And you have to develop one peak in one area. Try to be #1 in the world in that area.”

– Dan Shechtman

The above words of wisdom were just a sampling of those delivered by Nobel Laureates to an international audience of young researchers at the 63rd annual Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting in Lindau, Germany.

Nearly 90 U.S. delegates, predominantly PhD students in chemistry and related fields, were sponsored by the US government to spend a week in Germany with the acclaimed Nobel Laureates in our field and the rising talent from all over the world.

The German conference occurs annually to foster dialogue between Nobel Laureates and young researchers about major contemporary scientific challenges and their intersection with political, economic, and humanitarian issues.

Each day of the meeting, Laureates gave plenary lectures on a topic of their choosing. Some stuck to the purely scientific, describing their Nobel Prize winning research or their current research. Others described other passions and their intersection with science.

President’s Order

The quotation by Steven Chu (1997 Nobel Prize in Physics for development of methods to cool and trap atoms with laser light) above relates to his tenure as the US Secretary of Energy during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. He recalled President Obama beseeching him: “Chu, go down there and stop the leak.” Chu discussed this disaster and many other intractable problems in policy and the environment including the interdependence of the electricity and water supply, the trillions of gallons of water consumed on wasted food each year, and the carbon isotope evidence for climate change caused by fossil fuel combustion.

Science, Art, and Philosophy

Advances in medicine and microbiology were addressed by several laureates including Sir John E. Walker (Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1997 for the elucidation of the mechanism underlying the synthesis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP)) who imagined a future free of mitochondrial diseases, which can be transferred via mutated mitochondria in the mother’s egg. In a futuristic 3-parent solution, the nucleus of a fertilized egg may be transplanted to another egg containing normal mitochondria to avoid mutations from the mother.

Ada Yonath (Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2009 for studies of the structure and function of the ribosome) explained her Prize-winning discoveries and the ‘chicken or the egg’ question of whether it was proteins or the genetic code which came first in evolution. She says, “We think neither. The ribosome was first!”

Other laureates discussed their scientific careers and their intersection with art and philosophy. Richard Ernst (Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1991 for contributions to the development of the methodology of high resolution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy) shared his passion for Tibetan art, which he and his wife collect and study. He stressed the importance of widening the scope of your studies: “He who understands nothing but chemistry does not understand chemistry either.”

What Science Can Do and Cannot Do

Some also reminded us of what science can and cannot do for us and how to be a scientist. Mario Molina (Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1995 for work in atmospheric chemistry, particularly concerning the formation and decomposition of ozone) said “science doesn’t tell us what to do about climate change or anything else. It just shows us what is happening.” Dan Shechtman (Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2011 for the discovery of quasicrystals) stressed that scientific results require independent confirmation and replication of experiments. “That is how science is done, otherwise it’s just stories.”

Scientists Do Not Believe; They Check

Sir Harold Kroto (Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1996 for discovery of fullerenes) insisted that “scientists do not believe; they check.” And they should also enable and promote evidence-based drawing of conclusions, for example, by “discuss[ing] evidence for climate change rather than stating it as a fact, and let[ting] others draw their own conclusions.”

And most importantly, Peter Agre (Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2003 for the discovery of water channels) assured us, “Looking back on our careers, was it worth it? Absolutely, positively, yes.”