Sandy DeCrescent celebrates 50 years as an orchestra contractor. At one point she worked with 43 of the most talented TV and film composers in Hollywood. Today, she is still selecting the musicians and managing the orchestras for composer John Williams, who will be recording Star Wars in June, and for composer Randy Newman who just finished recording Toy Story 4.

Over the last decades, Sandy DeCrescent has managed to form an orchestra that is composed of 50% men and 50% women. impactmania spoke with Sandy DeCrescent about how Hollywood composers supported her becoming the first female music contractor for the film industry and the time she made Steven Spielberg run out of the recording booth.

BY PAKSY PLACKIS-CHENG

Sandy, how did you get started?

I dropped out of UCLA after two years because I ran out of money. I came from a very poor family. My father and mother saw no reason why I couldn’t get a job as a receptionist or anything to make money. I always knew I had to get out of that house—it was very abusive.

I worked all through junior high and high school. At age 13, I was five feet and nine and a half inches— never grew after that, but that was very tall. No one even questioned my age. I saved every penny toward college, but my car broke down, and I couldn’t stay [at UCLA].

I wandered into the biggest talent agency in the world at the time, MCA, in Beverly Hills. The HR person and I liked each other right away. She said, “I have to give you a typing test and a short-hand test.” I replied, “Okay, but I should warn you, it is not good. Not good at all.” [Laughs.]

She asked, “What is it you want to do?” I said, “I’m very good with people and I’m very good on the phone and I’m a great organizer. I’d be an asset to anyone you put me with.” They had an opening in music, but were looking for an older, experienced woman. I was 20. I said, “Could I just meet with him, do you think that could be possible?”

And only because she liked me, she introduced me to Bobby Helfer. I had a very rough dad, so I don’t get intimidated easily. I said, “I’ll work for free for a month, so you can see how good I am with people, just give me a month.”

That was the start of it. Then we reincorporated as Universal Studios. I ended up in the music department. My God, I was so thrilled, so happy.

What was your job like at Universal?

Let’s see, we had 18 television shows back then. There was no reality TV, there were very few sitcoms. There were all these composers—John Williams, Dave Grusin, and Alex North.

I prepared everything: the budgets for Bobby, the stage sheets, the phone rang off the hook, all day long. I managed to keep up with it all.

Bobby became very fond of me, he had no children but I fell in love with someone I shouldn’t have fallen in love with. He wasn’t married, but he was 12 years older than me. He was so engaging and spoke all these languages and read every book. I just fell for him. I realized he was never going to get married and he drank too much. So I left this fantastic job and moved with my friend Beverly to San Francisco.

I did find someone to replace me, an English lady, Rona, who was so charming and so bright. I said to Bobby, “You’re going to love her.” I spent about six weeks training her. She was wonderful.

About two years later I get a call. Rona had committed suicide. She left three-year-old twins and a six-year-old. It was so devastating. Bobby said, “Please I’m begging you, please come back to work. And I did.

I met my husband while I was working for Bobby. I had a little girl, Elisa.

Bobby began to get very, very depressed. One day he called me into his office and said he wanted me to send an addendum to his will to his lawyer.

I said, “What? What are you talking about?” He said, “I want you and Ron and Elisa to have money.” I was so scared ‘cause he seemed very depressed. He ended up committing suicide. I was so devastated.

I called several friends of his. Bobby was great friends with Elmer Bernstein. I said, “Elmer, I’m worried.” And he said, “No, come on. We all have times of depression.”

That must have had such an impact on your life.

I couldn’t believe it. There was someone who I absolutely adored, [film composer] Stanley Wilson. Stanley was everybody’s dad. He is the one that mentored [film composer with over 41 Oscar nominations] John Williams [known for his motion pictures music for Star Wars, E.T., and Jaws] and Dave Grusin [known for The Fabulous Baker Boys, The Firm, and The Graduate] and [composer best known for Theme from Mission Impossible and Dirty Harry] Lalo Schifrin. Stanley was the first one to bring in black composers.

He was one of the most wonderful human beings I’ve ever known. I always wished he had been my dad. But he had three daughters and I was close with the family and he knew I had been covering for Bobby. After the services, he said, “I’m going to offer you something. You’d better go home and talk to Ron about, because it’s not going to be easy…I’d like to make you the first woman contractor of Universal.” Honestly, Paksy, at that time there were no women music contractors.

Making you the first woman contractor at Universal and thereby in the industry, how gutsy was that of Stanley Wilson?

It was so gutsy. He really loved me as a daughter and I adored him. I went home and I thought about it. Ron, my husband, was scared for me. He said, “There’s going to a lot of hate toward you. And Paksy, to tell you the truth, there was more hatred by women than by men.

What is that about? The best supporters in my career in tech were all men. The women were actually the ones who wanted to get one over each other.

Well, it’s cultural on the one hand, and back then it was very sexist. Obviously, Stanley wasn’t. Back then, the musicians were awful and all the ladies up and down the hall of where I worked when I was the secretary no longer wanted to have lunch with me.

Some of them said terrible things about how I got the job—because, of course, I must have slept all over the place. In many ways, I guess I could thank my father because I didn’t let him break my spirit. He tried his hardest. And so I had a certain amount of toughness, not to say that, I didn’t get in my car on many nights and cry on my way home. Ron said, “Don’t ever, ever let them see that you’re upset.”

Paksy, I got a lot of hate mail, some of it threatening. It was awful. Ron went to the police with it.

These letters were from musicians?

From musicians—“No broad is gonna be my boss.”

I had been on that stage a million times, but not as contractor. When I first got the job, I walked down the stage. I noticed that every music stand had a little tin ashtray on it. You had to go through smoke when you walked on. So I put up ‘No Smoking’ signs.

That really endeared me to the guys. [Laughs.] And I began one by one by one to get women in the orchestra.

I’m not a musician; definitely don’t read a note of music. I have good ears after all these years, but that’s it. I’m very entrepreneurial. I found people without an agenda whose opinion I could trust.

Now, some composers have their own list, and I have to follow whatever they say.

One composer said to me, “I don’t want any women in the orchestra.” That was a gas. I said, “Really? I guess I’ll have to send you some.” [Laughs.]

And he said, “No, I meant that.” ”Why,” I said, “that’s not going to happen.”

I didn’t stack it with women, but I had lots of women in the orchestra. It was tough. If a woman got pregnant, then the male contractors would say, “Listen, I don’t want to get a phone call that you can’t come to work, ‘cause your baby is sick’.”

The women were scared, always scared, and pressured.

I left Universal after many years. I wanted to be my own boss, have my own company, and make things better for everyone, but mostly for women. My workers are now about 50% women and they are fantastic.

Sometimes it’s kind of lonely. I goofed up a couple of times and had dinner with a few people in the orchestra, and then other musicians complained, “Why wasn’t I part of that dinner?”

Do you prepare the women musicians differently than the men?

At one point, I started the hunt for a concertmaster. I found someone and she is wonderful. I told her, “I’m going to make you concertmaster, but I want you to be prepared. There are exceptions but most women will resent you.”

We do not only need to battle with some of the men, but we also have to battle many of the women. This doesn’t apply only to the music industry. What is your advice for women in the workforce?

My grandma was the only person who was really kind to me. She said to me once, “Don’t worry about what other people think. Who will know? I will know.” You also have to be a big fake. [Laughs.] There are times that I put this smile on my face. While I really want to go and just yell.

I never raised my voice and I’m tough. I’m not insensitive, but at work, you have to keep your decorum.

All these women over these many years, when they got pregnant they’d be scared to death. I got them pumping rooms at every studio once I left Universal. Before that, it was awful, you had to go into a bathroom, or God knows where, and pump.

A lot of the male contractors said, “That’s why we don’t hire women.”

Do you have any composers who were just really not on board?

I’ve got them all trained. [Laughs.]

I trained them. At one time actually, I worked with 43 composers.

And then my husband got esophageal cancer. We adored each other and I thought, What am I doing? The grandkids are growing up faster than I could even keep track of. I don’t need 43 composers.

I don’t ever wake up in the morning, Paksy, and say, “Darn, I wish I was going to be in a recording studio today.” [Laughs.]

One by one by one, I let go of everyone, but John Williams and Randy Newman. In fact, after Ron died, I was glad to be busy. My grief was beyond…I knew Ron would never want me to sit in a corner.

How many movies have you worked on?

I’ve done 1,100 movies plus!

What is your responsibility as an orchestra contractor?

When it was TV, it’s on once a week, there’s no time for you to make a budget. You just hire the orchestra.

But then when I struck out on my own, I didn’t want to do TV anymore. I mean 18 TV shows was insanity. Sometimes we had one series on one stage and another on another and I’d run between the two.

In motion pictures, you have to wear many hats. Right now at Disney, I’m working with six different people on Star Wars: the director, the producer, the executive producer, two other producers, and the lawyer.

I start with the composer’s wish list. Maybe the first day, the composer could have his or her dream orchestra. If it’s Star Wars, hey, anything you want John Williams! But not everyone is that lucky.

John Williams would say, “Sandy, here’s the instrumentation.” I pick everybody to be in it. It isn’t to say that in the beginning I didn’t have to keep working on the quality of the orchestra.

My number one thing is to make sure my orchestra is respected and paid properly.

You are known as respectful, tough, but fair to the musicians. However, I understand that AFM was initially not supportive of your appointment, but renowned Hollywood composers supported you wholeheartedly.

Paksy, the union turned it down. They said no.

They said, “She doesn’t play an instrument. You have to be a member of the AFM [American Federation of Musicians] to be a contractor. “No, we’re not letting her in.”

The composers who I worked with came to my rescue. They crashed, and I mean crashed, the next union meeting. It was [composer of The Magnificent Seven] Elmer Bernstein, [composer of Star Trek] Jerry Goldsmith, and Dave [Grusin]. There were about 30 of the best composers in town.

That night after the meeting, [composer of Mission: Impossible] Lalo Schifrin, called me. I was cooking dinner for my family. He said, “Sandy, you’re in, you’re in!” And I said, “Lalo, what are you saying?” He had that thick accent. “You’re in!”

I’ve had the most wonderful, and on the other hand, the most upsetting experiences. The wonderful so outweighs anything else. To look out at that orchestra and see all those women to be every bit as good as any man.

It would have been absolutely wrong if I just started pulling women in.

Women add a warmth and the men are fantastic, too. Right now, almost my entire woodwind section is filled with women.

You have to do the reverse now. You have to start looking for some men.

[Laughs.]

In the strings [section], it’s about half and half. I have two good lady horn players in the brass section. We have one really good woman trumpet player, but no trombones, no tuba. Only one woman for percussion, but the orchestra is 50% women.

That is better than most symphony orchestras.

There are supposed to—no woman, that’s shameful!

People don’t always appreciate the importance of music in a film. What would be a good example of where the music enhances the movie?

Yes, the music can raise the level so high or it can lower the level. Some of the scores that I’ve heard lately have no relationship to what’s on the screen. It takes you out of the movie.

I got to go see Jaws with John before he wrote the music. He said, “Come on baby.” He’s always called me baby. “Come on baby. Come to the screening.”

There’s the scene where they’re letting out the barrels at the very edge of the boat and all of the sudden the shark jumps over the side of the boat. I screamed and ruined the take. The red light was on. The red light was on! [Director] Steven [Spielberg] comes running out of the booth and I am so humiliated.

He said to me, “Did you really mean that?” I said, “Steven, I don’t scream when the red light is on, but it was so frightening!” He said, “You’re a normal person, that’s the best review I will get!”

I was humiliated. I’ve not done it since! He’s a wonderful man, too, Spielberg.

You have worked with all the greats in the business.

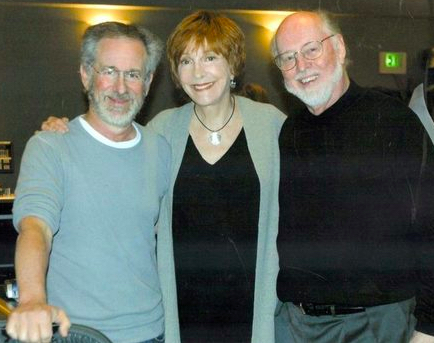

Spielberg had a party for John when he turned 75. I’m not a big drinker. I was sitting at a table with the people I know. I had a scotch and then another half. My limit is one drink, never more. I don’t know what came over me. Steven and John came over and said, “We need to get a promise from you. Do not retire before we do!”

You worked on thousands of music scores. What are some of the pieces that stand out? What does Sandy listen to?

I love Dave Grusin’s music. I have several of his sound tracks. They are still so current. He really was brilliant and under-appreciated.

John just did a CD with [German violinist] Anne-Sophie Mutter and it was so wonderful. She approached John and said, “I want to do themes from your movies.” John orchestrated it for her and the orchestra. She played Schindler’s List. To this day, I cannot hear it without falling apart. I knew it was going to happen on the Tuesday. So I wore absolutely no makeup, and it’s a good thing I didn’t.

Almost every film with John is so memorable. I loved Hook.

I loved John Barry’s Out of Africa, not the man, but the score!

When you listen to a score do you think of the time it was recorded: we had a budget crisis, a musician got sick?

On Schindler’s List, I always think about [violinist] Itzhak Perlman. We flew him in from New York. He came in a wheelchair and was seated so that he could see John [Williams] conducting, but also see the screen. At one point, he put his hand up, and called me over. He said, “I need my chair moved”—he had tears coming down his face—“so I don’t see the screen.”

He was so emotional. I’ve never forgotten that.

I love Memoirs of a Geisha. [cellist] Yo-Yo Ma came in, another splendid, wonderful person.

Here you have these famous people who have no attitude. Sometimes, I deal with more egos than you can shake a stick at. [Laughs.]

What words come to mind when you look back at your journey?

I said to my daughter this morning, I look back at months where I was at the top of my field. I had so many movies that I’m sure one eye was going one-way, and the other eye, the other way.

There was a month where I did 12 movies. Some movies are only two or three days. It’s all about the number of minutes of music and how fast a composer goes without sacrificing any quality. John Williams does 15 minutes every three hours.

He records fifteen minutes of a film score in three hours?

Sometimes he has a hard day and he only does 14. I’ve seen him do 17. He is the most incredible person, he’s organized, he’s a great conductor, and it’s all laid out so perfectly.

There are people who are lucky if they break ten minutes in three hours.

So it’s based on number of minutes of music. Some scores have only 40-45 minutes. But then you get a big action movie. During Star Wars, for example, [producer] J.J. [Abrams] wanted to change something. Three weeks after we had done a part of the score, J.J. comes back and says, wouldn’t it be wonderful if we did this, this, and this? I love J.J.

J.J. said, “John Williams is my hero, Sandy. When I was a little boy, in a small school in the Valley, we were each given a board that we could paint on.” On J.J’s board, he wrote at the top, Jaws. Underneath in huge letters Music by John Williams with a picture of a weird looking shark. [Laughs.]

J.J. said, “I used to lie on my floor as a little boy and listen to music by John Williams. And now I am here.”

This must impact the quality and the end product—people can only create magic because there’s this connection and love, right?

I can take this fabulous orchestra of John Williams and put them with another conductor. And they don’t play well. It isn’t even about the other conductors conducting, but more about how they treat the orchestra.

You put them with John Williams or Randy Newman who show such love to the orchestra. I’ve had people say, “I didn’t even know I could play that great.”

It’s so true; there is this whole psychology—it is a wonderful magical thing that happens.