CALL ME BY MY NAME

And all we’ve been-

Empty letters on cold stone-

Stillness- engraved with memory’s

Blunt blade-corroded by time as bones.

But if only an echo

Could remain, the ego

In a name

For reflected, it’s

Immortality

-Exposed-

Like skin,

Bearing a name

It feels bare

-To be-

Undefined beings

Identified

Striving not to be filled by

void

Anonymity

Is a muddy trench:

If you slip, you fall asleep

Swallowed in the pit.

BY DENIDA DODA

Edith Bruck is a Hungarian writer born in 1931 into a poor Jewish family. In 1944, her first trip took her to a ghetto and from there to Auschwitz, Dachau, Bergen-Belsen. She survived the deportation, of which she has testified in her works, after years of pilgrimage she finally arrived in Italy, adopting the language. In 1959 she published her first book, Chi ti ama così.

In 1962 she published a book of short stories, Andremo in città, from which her husband Nelo Risi drew the homonymous film. She is also the author of poetry and novels such as Le sacre nozze (1969), Lettera alla madre (1988), Nuda proprietà (1993), Quanta stella c’è nel cielo (2009), transposed in the film by Roberto Faenza Anita B., Privato (2010), La donna dal cappotto verde (2012), La rondine sul termosifone (2017), Ti lascio dormire (2019) and Il pane perduto (2021).

In her long career, she received several literary awards and was translated into several languages. Among others, she is a translator of Attila József and Miklós Radnóti. She wrote and directed three films and played in theatre and television.

“What’s your name, man?” asked Cyclops Polyphemus, and the cunning Odysseus answered, “Nobody is my name“. And by deception, Odysseus blinded the giant by sticking a stake in his eye and Polyphemus shouted in pain: ”Help! Nobody has blinded me!”

But the other Cyclopes didn’t come to his rescue because “Nobody” was trying to kill him.

To better understand what it really means to be anonymous I asked the former number 11552 because often the story is deleted but the numbers remain tattooed…

It is the dawn of April 15, 1945, the number 11552 barely stands. It is lined up, waiting for the appeal that never happened. In the camp of Bergen-Belsen the scent of freedom spreads in the fetid air of Europe, polluted by the fumes of burnt flesh.

Americans gave HER the name back, the dignity of being a person.

Denida Doda interviewed Edith Bruck on April 15, 2021.

First of all, I wanted to wish you a happy 76th year since your liberation!

Thank you, yes, today is indeed the anniversary of my release.

Who is Edith Bruck? When you look in the mirror, who do you see in the reflection? What do you think?

That I have grown old. [Laughs.]

I recognize myself, I see in my face features of my mother. It’s always me, in the sense that I’ve never lost my identity. I remember when I was a child, I remember everything, I have no identity problem. Actually my real surname is Steinschreiber.

Edith Steinscreiber.

I never had any doubts about my identity because I was so “tattooed in the soul” that I never lost myself. I am the one who survived and I’ll always remain that one and that is my deepest identity. I’m always present to myself, I didn’t lose myself in any part maybe because I lived a unique thing, a terrible thing so that’s me, in that cage always and I will remain there because, at the same time, I don’t want to get out. I testify in schools, I go everywhere, for many years now, for at least 50 years so my identity is always present, always, from dusk until dawn and from dawn until dusk.

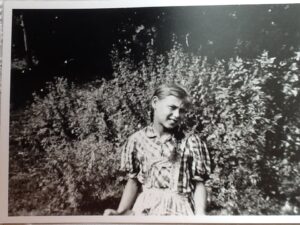

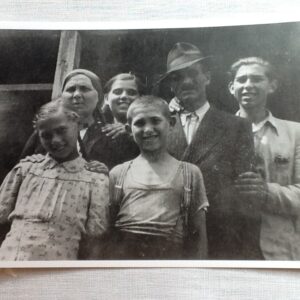

Steinschreiber family. Hungary, 1942-’43.

Who gave you the name, what does it represent to you?

My name was chosen by a doctor who lived in my grandparents house, he rented the studio there. It is not a frequent name in Hungary where traditional names are usually assigned. This name is more French than Hungarian but I like it, indeed, my sisters used to say that I had received the most beautiful name of the family. Even if it is not so, they also had nice names.

My name is me. Myself, it means me. It’s me.

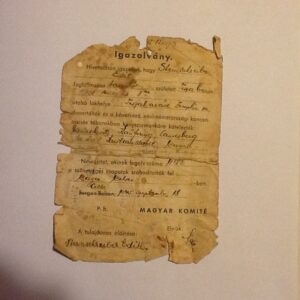

Edith Bruck’s repatriation identity document released after the liberation. It shows the serial prisoner number (11552).

The back of the identity document dates 22 October 1945. Today, this document is preserved in Rome’s Museum of Shoah.

What does the number 11552 mean to you? How does it feel to be anonymous, to have your identity removed, to be reduced to numbers? How does it feel, all of a sudden, to not exist anymore?

I’ve been a number for a whole year, but during that year, for example, a cook in Dachau asked me: “WHAT IS YOUR NAME?”. He told me he had a little daughter like me and he gave me a small comb, for the hair that was growing back. When I heard my name, after saying it, I was absolutely amazed because there was no one to ask you such a question in those places, I had become accustomed to being called with the number 11552, I had become 11552. I did not believe in my eyes, I did not believe in my ears when he asked me my name. I felt like I existed, I was reborn. At that moment I realized that I was there, that I was a human person, not just a number.That small gesture was very important because it took so little to feel alive, not to lose hope, to think that it was worth fighting for life. Because there was no way for someone asking such a question in the concentration camps. It was a miracle, I can say. I don’t think anyone was asked “What’s your name?” after spending a year without a name but just a number. To that number you had to answer. Then if you heard your name and they called you by name, if something like that happened, you would have seemed to live, to exist again. In that brief moment you think the world could be better, that it’s worth fighting for freedom and not giving up.

How did you regain your identity after all this time, a year gone by without having a name. Is it hard to find yourself?

It’s very hard to find yourself. I believe that, after all, I found myself only in Italy, also because I traveled half the world before landing in Naples. I believe that identity came then, especially through the language.

When I learned the Italian language, and wrote the first book, I finally began to exist in the true sense of the word. I AM. And so I’ve written at least 30 books since then, language means everything to me. Italian is a language with which I can express myself, and this is fundamental because in no other language could I have written what I wrote.

In my native tongue I would not have done it because my native tongue hurts me, it reminds me of some very painful things.

In the Italian language, I hide myself, but this language gives me total freedom and this is very important because I do not feel fully, it has no deep roots and does not remind me of anything.

When I write the word “BREAD”, in Italian for me it is the bread of the baker while when I write in Hungarian the same word, I see my mother in front of me: she is swollen, so fatigued, all her figure, shoes, legs, and sometimes I even cry. It reminds me of some very painful memories and therefore for me, this adopted language of mine, is a wonderful refuge. It completes my identity and I exist as Edith Bruck, as a writer in the Italian language.

Today I am also very recognized and therefore it does not give any more problems absolutely. At the beginning it was difficult because every language is very difficult and so I think I have always written better, in every book a little maybe I have improved. That’s as far as I can go.

What do you think it means to lose memory, so the past, to forget the names of people, of our ancestors? For example, I remember the episode in which Achilles and his mother discuss and Achilles’ mother, Thetis, tells him that if he goes to war he would die but his name would be remembered forever. Achilles died in the Trojan War and, in fact, we still remember him today.

In addition, the Talmud also says that a person is forgotten if his name is forgotten.

In your book “The Lost Bread,” you recount an episode in which, in Bergen Belsen, you are asked to drag the bodies of the dead men to this pyramid of corpses, you wrote that someone stuttered their name and their origin while another had told you “Tell them, they won’t believe it, tell them if you live for us too”.

This was one of the most painful things in my opinion. Because when we came back, we did the famous death march (600 km) from Bergen-Belsen in Saxony to Kristianstadt in Sweden.

Then they brought us back when by then more than half the people had died and we arrived in a field of men. This field was full of corpses, full, full, full. And they told us that if we brought these corpses with a rag tied to their ankles into the tent of death, they would give us soup, in other words, this slop they gave us to eat. Two of these people were now in total agony, they could stutter their name with great difficulty and one declined his generalities while the other begged me to tell.

I said yes, of course. I kept my word, to some extent. I would have told even if he hadn’t asked me because I started writing in ’46. I started writing because no one listened to us and I had inside this boulder that I could not bear. I needed to tell about our suffering because I could no longer keep all this poison inside. I started writing in Hungarian but then I ran to Czechoslovakia, then from there to Germany and made a long journey before arriving in Italy.

Edith Bruck marries Nelo Risi. Rome, 1966.

When I arrived in Naples, there was this vibrant air with the songs that you could hear at every step. I said to myself: Maybe here I can live. Somehow I felt welcomed, by the air I mean, not by people because I didn’t know anyone and I didn’t even know a word in Italian. After three years I started writing the first book.

All I do is remember: I go to schools, I go everywhere. Memory is life, memory means existence, if there is no memory, you no longer exist. I treated my husband Nelo for over ten years because he had lost his memory, he had Alzheimer’s, and I was his memory too, not just mine. I believe that without memory man is finished, he does not even remember himself, not even who he is.

In the end, my husband even asked me who I was, and that made me sink into my deepest memories, to when I had no name. He was lost. It is no longer a life, if you take away the lucidity, you take away the thought of man, he no longer exists. Memory is everything, memory is life: it is past, present and future, it is everything. It’s existence.

Forgetting would be like erasing everything that happened, pretending none of it happened. But it is impossible, it shouldn’t happen, it is absolutely a moral duty to go on talking and writing. Indeed, if I could pray to God, if I believed, I would only ask for memory, to sustain me until the last day, in order to be able to say, because there is still much to say, especially today more than twenty years ago.

Il pane perduto (2021).

In your book you quote the famous phrase pronounced by God when he appears to Moses in the form of a burning bramble: “I AM WHO I AM”. This sentence reveals to us the identity of God but at the same time it doesn’t tell us anything.

It is also said that at the beginning there was the word and the word was with God and the word was God. In your opinion, what is the real power of names? (Latins used to say nomen omen.)

The name itself is worth nothing if you don’t have a certain position or power, so if you’re any person, instead a person whose name is associated with something great, some act or something considered important and impactful in society: writers, philosophers, historians, scientists, then the name counts.

In my opinion, we are the ones who make our name famous, in the sense that one writes or tells or does something because he feels the need, because he has in some way a talent to express himself, it is not that everyone runs after fame and has as a goal to make his name great, probably just some emperor and despot.

I never thought to write to make me known or to make my name known. I write because I need to write. For me writing is really…breathing, for me it is oxygen. I will never stop writing for sure as long as I have something to say.

Edith Bruck in her library. Rome, 2021.

We write because there is always something to write about, there is always to protest, always to denounce. Because there are many things that do not work even today as yesterday and as it will be tomorrow essentially: discrimination, racism, anti-Semitism have returned.

Everything that happens, in any part of the world, concerns me, perhaps also because I have been discriminated against. I know what it means to not be wanted, to be hated. That’s why I will go on in schools, in universities, everywhere to speak. I get this response from the schools through the letters I receive from the students. And if I can change even a few people, I think my life has been useful and my suffering has not been in vain.

If I can do anything to improve this world full of injustice and intolerance, I am right on guard for all the people who suffer for all the people who are in some way marginalized. There’s always something to say, unfortunately, if only there was nothing to say…

Everything that hurts others also hurts me. The others are not the others, we are always with them, with everyone. We have only the good fortune to be able to express ourselves because not everyone can express themselves and that is why we must also speak for others. I feel very privileged and I always write things that hurt me deeply.

When I was evicted from the house where I lived, I lived it as if I were being expelled from the country, as if I were being deported. My husband told me: “Well, they just want to raise the rent, don’t worry.” But we survivors live everything differently. We have a very open, exposed, naked feeling in front of things. Everything that hurts me sooner or later becomes a book.

Your life can be defined as a sort of Odyssey until you found your Ithaca, Italy. You have traveled to many different countries, so you know what it means to be a foreigner, what are the positive aspects of traveling and what are your best memories?

In general they’ve been quite unhappy trips.

I have been in many countries but I went above all to visit those who had remained of my family, who were scattered in the four corners of the world. It has always been a family visit.

I went to Ethiopia with my husband to shoot the film about the poet Arthur Rimbaud, after a month I decided to go back because I had lost eighteen pounds. I was suffering from the situation in which the indigenous people were. They were so hungry that they tore the pieces of bread, I couldn’t bear the misery. I couldn’t see the hunger of others so I went back. I can’t see the people suffering, starving. Let’s say I haven’t been anywhere happy. In my travels I have seen many beautiful places and beautiful things but happiness is another thing.

I didn’t make much of a tourist, apart from some trips with my husband, like the one in Sardinia that was very nice. In Stintino [Stintino, a small town on the northwest tip of Sardinia] where the beach was still totally deserted, it was the first holiday we had together. I’ve always worked, all my life, no time for fun.

You said that happiness is something else, so what is happiness for you?

When I think about happiness, I remember the best memories of childhood, for example when they gave me the only new dress and I tried it in the yard. I was very happy, I was happy even when Mom cooked a cake on Saturday. I was happy to an extent that I have never been after childhood, despite poverty. Because when you’re poor, you appreciate everything you get. I remember a pair of rubber boots that my father brought me, and it was hard, almost impossible to have a new thing, I danced on the couch and I broke it but I was happy. I will never be as happy in my life as I was in poverty, when I received something more: when there was enough to eat, when the teacher, as a reward, had given me a paper swallow, when my friends used to say “hi” to me, because they also stopped saluting me afterwards. Such small gestures made me very happy. I’ve never been as unhappy as when my neighbors and my classmates turned away to avoid me.

After, life is totally different, it is a new life but you are not new because you carry within you the past, everywhere, at every moment, wherever you are you carry inside of you what you have lived. So that innocent happiness, that poor happiness is over, it doesn’t come back.

I’ve been happy with my husband for many years, I felt fulfilled both with him, and also when I write a book, a poem, when I publish a book, I look at it. Then I don’t read it anymore as if it didn’t belong to me. Even today I opened a book and I could not read even a line because it hurts me to read it, I never reread my books. But writing is a great happiness because it comes as a fruit, as when you open the tap, the words flow, it is the book that writes itself.

I wouldn’t even want to use the word happiness, because happiness is a moment in life. You can be unhappy even seeing what happens in the world, even for others, not only for yourself.

Edith Bruck is awarded the honor of Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic by the Italian President Sergio Mattarella. Rome, April 29th 2021.

In your experience, what has changed and what is changing compared to the past in immigration and how immigrants are seen?

The world in general is a disaster. Unfortunately, all these things that I had listed before have returned, this intolerance towards others, towards different people and also racism. Anti-Semitism is returning throughout Europe. And then they’ve tried to erase history for what it is, to mystify everything, to flatten everything and instead of confronting the past, countries prefer to deny what happened or falsify. For instance they taught in the school of my small village in Hungary that it was the Germans who took us away, which is not true because it was the Hungarian fascists.

The kids in the schools study little history, they are taught badly. In schools I have had an enormous experience for many years. I think it is very important to tell young people to defend their future from what was our past because it can serve and it is very useful listening. In my view, young people listen much more than adults because adults, not to mention old people, perhaps feel guilty about what happened, in the total interference of Europe, I mean. Instead, in my opinion, young people must know the true values of life and always be on guard because maybe today it’s someone else’s turn but maybe tomorrow it’s up to us.

It is not that the world lives in peace and harmony and in love. On the contrary, in some way it is necessary to teach tolerance and respect for others and I spoke with Pope Francis about these things when he came to visit me at my house in February.

Memory is very important, keeping memory alive, it is very important to transmit memory without sparing ourselves. We survivors are now very few, very few and so we try to do, at least, I try to do what still allows me my strength, my energy, and my memory that I hope will support me to the end.

Primo Levi, in his book If this is a man, wrote: “Nothing more is ours: they have taken away our clothes, our shoes, even our hair. If we speak, they will not listen to us, and if they listen to us, they will not understand us. They will also take away our name: and if we want to keep it, we will have to find in ourselves the strength to do so, to make sure that behind the name, something still of us, of us as we were, remains.”

Where did you find the strength to keep your name?

Well, it seems perfectly natural to find my name after the war like Primo did. In fact his name has become quite famous. We were close friends anyway, from the seventies until the last day. He thought he started writing because he’d been to Auschwitz, but I think he had a natural talent for writing. I, too, would probably have written even if I had not been at Auschwitz because I was about six when I asked my mother why there was all this injustice in the world. I used to see very poor people, in misery, crazy people tied up in basements, people throwing rocks at them. I came home many times crying to my mother why people were so bad. She turned only to God but I always turned to men, to human beings. I believe that we must leave God out of what happened because it is not explainable in any way. When the observants or the ultra-Orthodox say that God wanted to test his people, it seems to me a blasphemy.

I think believing means loving your neighbor, helping, if possible, and having mercy. I also had pity for the Hitler-Jugend, when they spit on us I watched them without hatred, because I do not know what hatred is. I do not know this feeling. I felt sorry for them. And that’s why I even wrote thanking God or no matter who because I don’t know what hatred is. What I feel is much pain for humanity itself that does not learn anything from mistakes, that does not realize that it is going towards its own self-destruction by poisoning land, sea, rivers,… everything.

Man perhaps has a sense of ancestral guilt. I do not understand the reason why he does not respect the soil, the place on which he lives, life. And so I don’t see the world improving in any way, as if it’s running towards its own end.

Pope Francis visits Edith Bruck. Rome, February 20th 2021.

Do you think there is a way to improve this situation of the man who seems to have almost a self-destructive nature?

What little I can do, I certainly do. When I spoke with Pope Francis, when he mentioned parts of my book, I told him that even a drop in the sea is useful, in this black sea in which we live, we try to survive. There is good and there is evil, the problem is that evil often wins over the good. But if we can do a minimum of good, we must do it. We can all do it, not just those who have power. We just need to educate children differently. Teach them to respect their neighbor and share what little they have, help. I think that education is very important both in the family and in the school.

What advice would you give to today’s young people in order to find their true identity and their place in society? A youth whose future seems uncertain, after all these changes and what is happening.

First of all, to communicate with the elderly, with the old, to listen to how they have lived. It is precisely the elderly who are loved least today. The family, even in Italy, tries to move them away from home, hospitalize them for anything, instead of treating them inside the house with the people around. They can’t wait to get rid of them.

Even now with the pandemic, most of the victims were the elderly, and this is a disaster because if we lose them, we lose our history.

Then also the parents try to spare the children from telling them their life. They do not talk, they have no dialogue, there is no communication in this world in which we communicate even too much. There is no communication because young people live among themselves as if they were a separate entity.

Therefore, in my opinion, they must have more dialogue especially with their grandparents and they do not have it because they flee and therefore the young people find themselves wandering in the void. This is why they do not appreciate, they do not know what value is, what value to give to bread, what value to give to life. Convinced they’ll never fall.

Edith Bruck during this interview. Rome, 2021.

Also because the old ideologies are all blown, now I do not know what a young man can believe in, it has remained, in my opinion, only humanity: to behave well with others, not marginalize, not despise.

You have to love your neighbor because no one loves their own neighbor as they should but at least respect and tolerate. Besides, there is also this incitement to suicide, with social media and the tragedies that happen. Today’s young people really do not know and are not able to value what they have.

I don’t mean there should be more poverty than there is so they can appreciate what they have. They do not know what life is, they play with life. Life is not a game, life is a precious thing, it is the only one we have and it must be valued.

From certain points of view they are also somewhat spoiled because they do not know NO as an answer. We have known the NO in life, both in poor childhood and after. We have known a world of NO, while the kids now know only the world of YES, and this is not good, this damages them to some extent.

Not to mention reading, they don’t read much, they prefer to play with electronic things. Reading is very important, teaching in schools seriously the past, the true history, not mystifying it. But then there is this hide-and-seek of what happened. Europe, to some extent feels its guilt for what happened, I always refer to the disaster of the Shoah, because something like that has never happened to that extent, of that kind for racial reasons, not only political. I believe that they must know in their own interest, not in my own because I have already experienced what was the worst in the world. It’s for their future, for themselves.

“And while forbidden to go near the wire, WE SHOUTED OUR NAMES, asking for their names, throwing them some stolen potatoes at the risk of our lives.”

The students of Messaggero Veneto Scuola are part of the impactmania’s internship program for the 2020-2021 academic year. A series of migration topics were explored in this Program that will culminate in an online exhibition and presentation, May 2021.

COVID made us all Digital Nomads, however, it didn’t stop us from cross-cultural, interdisciplinary learning.

Denida Doda was born in Udine, Italy in 2003. She is currently attending the fourth year of scientific high school Giovanni Marinelli. Denida is part of the youth editorial staff of the local newspaper Messaggero Veneto and part of the impactmania student internship program.

Photos: Edith Bruck. Featured image: René Magritte, La mémoire, 1948.