BAFTA winner: Never Alone — a Game that Matters

BY PAKSY PLACKIS-CHENG

After speaking with Charita Castro from the U.S. Department of Labor, The Office of Child Labor, Forced Labor and Human Trafficking, whose team launched an app that matters: Sweat & Toil, impactmania caught up with Alan Gershenfeld, Co-Founder and President of E-Line Media, who built a game that matters.

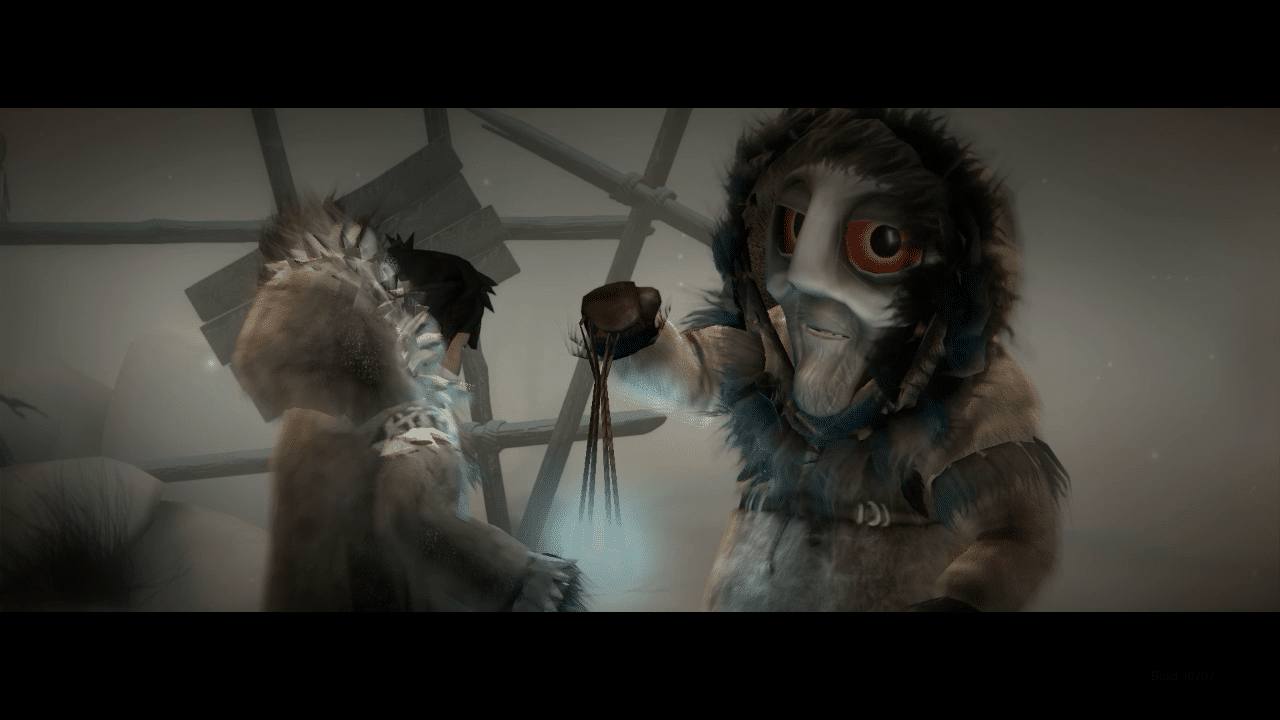

Never Alone, a storytelling game sharing Alaska Native culture, was developed out of a collaboration between E-Line Media and the Cook Inlet Tribal Council of Alaska. The game went on to win the BAFTA Games Best Debut of 2015.

A collaboration between E-Line Media and the Cook Inlet Tribal Council of Alaska

What is Alaska like in the middle of winter?

It’s exactly like you’d expect. We did a lot of our research up on the Arctic Slope.

The core development team of about 12-14 people built the game in Seattle. We had as many as 30 Alaskan Native elders, writers, and community members work on the project. The Alaskan Native writer, Ishmael Hope and our cultural advisor, Amy Fredeen, were very much integrated with the team. Then, many, many trips up to Alaska to meet elders, artists, and writers and many, many trips for the Alaskan community members down to Seattle.

How long did the development take?

From the time we first met with the tribal council when they proposed the idea of a video game company to the actual launch of the game was about two and a half years. The production funding was entirely by them originally. What is interesting, we constructed a deal where there would be a revenue share on the backend.

They’ve actually converted their profit and the equity in our company. They’re now our largest shareholder. The chairman of the tribal council [Gloria O’Neill] is our chairman. What began as a two-day consulting is now a lifelong partnership.

With such a competitive gaming market, how do people even create a space for themselves? It must be even more difficult for developers who’d like to create games that have a purpose in addition to profit.

As a planet, we spend billions and billions of hours a week playing games all over the world, all ages, on many different devices, platforms, and genres. The game industry is complex and diverse and constantly changing. Developing games for the mobile market, Android, Apple devices, is a very different ecosystem than developing for the consoles — Sony, Microsoft, Nintendo — the machines that are in the living room connected to the TV, which is different yet from the PC … which is different yet from the emerging platforms like virtual reality and augmented reality. There are really many different businesses within the game business. There are regional differences, differences between casual gamers and what they call mid-core and core gamers in terms of gaming literacy.

There are very different business models. Mobile is primarily a free-to-play — I would call it free-to-start — model. We’re seeing a lot more digital distribution across all the platforms. But you can still put games in a box and buy them at Best Buy or Walmart, which are very different distribution methodologies.

So it is a complex and a fast-moving industry. There’s a growing gap between a vibrant indie game factor, and the AAA, the big publishers who make Madden NFL or the Call of Duties that can cost upwards of $100 million to make and market.

Indie games can be in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, labors of love, and are often digitally distributed.

The challenge there is, how do you rise above the noise? How do you make people aware of a quality indie game? I would say game making is a craft. It’s not a commodity. The folks that can make truly, deeply engaging, immersive games are great artisans like great novelists and great filmmakers.

It’s a unique craft. Like film, it’s often a collaborative craft. While there’s often a powerful creative vision behind a game, you need strong lead technology, art, production, and sound. For some of the games, one person can do all of it. For Call of Duty, it’s five or six hundred people.

But there is an enormous opportunity because more and more casual gamers are coming into the market.

Never Alone screenshot

Are you seeing more of the larger companies going into purpose in addition to the profit game making, like educational gaming, or do you think it’s still very niche?

Through Activision, I had experience working on the big triple-A franchises. I got really interested at the time in the billions of hours that mostly tweens, teens, young adults were playing our games. I was wondering if the games can do more, much like great movies, great novels, in terms of the themes they explored and the perspective they provided.

I became the chairman of a nonprofit club, Games for Change, that specifically seeks out foundations, government agencies, universities, social entrepreneurs and connects them with the game industry, mostly through a big festival in New York every year; in fact it’s coming up in June.

I was amazed: I was tracking hundreds of millions of philanthropic, public-interest, and academic dollars going into games for some sort of learning impact. The big foundations, Gates, MacArthur, the big government agencies, National Space Society, Department of Education, and a lot of the big universities were all funding through various grants, philanthropic funding, public-interest funding, games for some sort of public benefit. But I was not seeing a lot come out the other end at that point that was genuinely competing for discretionary time and dollars in a consumer space.

I was also not seeing a lot that was meaningfully replacing time or money in structured learning in school, or informal after school. So we founded the company E-Line to actually help close that gap.

To bring the rigor of an Activision, not just from a development, but a publishing methodology, to the philanthropic and public-interest sector, by trying to do more effective partnerships, so that we could both make great gains, money but also make some sort of meaningful social impact… It is very hard. Games are entertainment, and they’re technology, both of which are hard in competitive industries, and making meaningful social impact is hard. But it is possible, and we’re starting to see more and more success stories start to emerge.

How can games help drive social/cultural impact?

Games have unique attributes, as opposed to other media formats. Games are interactive; they let you take on a role or an identity, step into a problem space, explore the problem, and fail safely. You get feedback from the game, from peers, from mentors, and develop halfway to mastery as the game designers define it.

That’s very, very powerful; in many ways, that’s good learning.

Are we going to a point where every goal we have is going to be gamified?

Game designers tend to not like the word “gamification.” There’s a feeling with the word gamification that it tends to focus more on extrinsic rewards. If you do this, you get this reward. It will tow you along versus the intrinsic reward of “I want to immerse myself in this world.”

One of my favorite definitions of games is it’s an invitation with a contract. To me, the best games are truly invitational in that you choose to do them. It’s not like you go to work and you have to do it and you’re pulled along with some extrinsic rewards.

The contract is the rules of the game and the rules of the social community around the game. Often, the community around the game is as powerful as the game itself.

There are definitely models for effective gamification that are often quite different than the models of truly immersive, powerful, interactive entertainment experiences.

But yes, the core principles of what makes games so engaging definitely can be applied to different sectors and different disciplines.

Is the average parent embracing the fact that children are gonna learn through playing a digital game?

When I was running the studio Activision in the ’90s, games were pretty much vilified by moms, dads, Republicans, Democrats; it was pretty bipartisan — except for those [who] were really immersed in playing them.

That has changed. The sector has gotten much broader. In fact, most commercially successful games, like SimCity or Civilization, clearly are games that are thoughtful and hugely commercially successful.

You’re seeing a generation of gamers becoming parents, so they’re more comfortable with it. They see that playing lots of games growing up did not adversely affect them.

You are starting to see games pop up in schools and in workplaces. There’s still much debate. I would say when I speak to parent groups, it used to be all about the violence in games, which is a very textured, complex issue. Now, I would say the number-one concern is the amount of time kids spend.

Minecraft is probably the first question that comes up because it’s such an astounding phenomenon. There are probably a hundred million kids, all of whom really identify with the game, the community. Minecraft — this is one of the most powerful education platforms ever created. There’s so many different things you can be doing in Minecraft, many parents are just sort of mystified.

They want to help deconstruct it. What is the optimal amount of time their child should be playing a game? Is it safe? How do they interact with other people? There are very real questions.

There’s a lot of research around use and digital media at different ages. There are centers of excellence like the training center workshop. There are folks publishing and aggregating the research to help guide parents around not just games but digital media more broadly, and frankly for adults, as well.

You are an advisor for the Sesame Workshop and PBS Kids. How do you support them making decisions in this world?

The investors for our company include the Joan Ganz Cooney Center, Sesame Workshop, the Tribal Council, and the Smithsonian. I’ve always been interested in public-private partnerships — how you could get the best of both, if you will.

I can point to literally hundreds of grant-funded projects where they were just starting to crack something: The grant funding runs out.

That’s why we became very interested in developing public-private partnerships. We, the stakeholders, define the impact, either internally judged or externally judged. But then, we can strive towards a sustainable business model.

Alan Gershenfeld

You are making impact investable.

Yeah. It’s exciting because it also enables us to work with some of the most amazing pioneering thinkers wherever they live: pioneers of IT on the future of digital fabrication materials, the folks in preventing gang violence, cultures around the world or with people who care about the future of the ocean.

And as long as we agree on what we’re trying to do and we’re all in the same shoes, it’s entertainment, it’s technology, but there’s a good chance something powerful will emerge.

What do you think is needed for social impact?

It has to appeal viscerally… whether you’re part of the team that’s conceiving the impact, the ones who are implementing it, or the beneficiary that ideally becomes the innovator, having an understanding and a joy around it.

I think the head, the heart, and the hands have to be incorporated at all levels.

An ecosystem like Minecraft, for example, has a very powerful community of modders that adapt and extend the platform and reach entirely new audiences. We participated in the Minecraft Edu mod for teachers and did a mod around quantum physics. This took the core game and vision in a way that was very different than the original team ever even imagined. But they were smart enough to create the platform, the tools, and the community to empower this middle tier that can then empower millions of others.

I think the same is true in terms of social impact. They often have powerful visionaries and lots of people who can participate in the community and benefit in some form. But what’s often overlooked is the middle tier of folks that deeply identify with the mission or extend the ecosystem in ways that the original visionaries or founders couldn’t.

Do you have an example of an ecosystem that was transformative?

Something like Wikipedia.

That’s really an ecosystem where the founding group really have an aspirational vision that a living encyclopedia should exist in the world. Many people buy into that vision. Then there are domain experts in all the different areas that Wikipedia covers, and people identify with that. Then there are editors. Then a hundred million people or so benefit from it.

That’s very, very powerful.

There can also be negative ecosystems, with destructive ideology that are very invitational, that provide aspirational pathways, provide a community, a sense of belonging…

Who has left an imprint on your professional DNA?

Because I started in film and I naturally think in terms of stories, a lot of the things that influenced me early on were really powerful movies. The movies of Miloš Forman and Hal Ashby were very, very impactful for me, in terms of how those movies explored the human condition in ways that just made me want to make movies and impact the world.

And so the emotion that comes through from those, connecting them to the power of interactivity and games, has been a core focus for a lot of the work that I do.

What’s next?

The company spent quite a few years exploring different contexts for games and digital media for impact. We’ve done work in the developing world. We’ve gone into about 15,000 schools with our projects.

There’s a powerful market, in terms of how games fit into all the disruption that’s happening in schools as textbooks start to go away.

And learning becomes unbundled as it gets re-bundled in a blend of tech-mediated/ non-tech-mediated with new learning spines that sport new dispositions in literacies. But they have to be part of a much larger vision. We, as a company, have decided that we want to do more games like Never Alone…games that compete in the consumer space, that provide new perspectives, open up new worlds, provide tools to create new worlds that really engage and inspire and empower the players, but are competitive as any game out there — the way a great movie would be that would win an Academy Award, or a novel that would stand the test of time. We believe games can be ultimately as or more impactful than other media because these can become ongoing communities that could live for a long, long time with very, very powerful tools embedded in them.

We want to share and celebrate cultures that don’t appear in games. We want to tackle the big social issues of the world in compelling means. We want to create games where folks can see the future and build the future. That’s our passion.

Alan Gershenfeld has spent his career at the intersection of entertainment, technology, and social entrepreneurship. Prior to E-Line, he served as Senior Vice President of Activision and was a member of the executive management team that rebuilt Activision from bankruptcy into a profitable industry leader with more than a billion dollars in revenue. Gershenfeld is a Founding Industry Fellow at the Center for Games & Impact at ASU and serves on the Board of Directors of FilmAid International. He also serves on the Advisory Boards of PBS Kids New Media, Creative Capital, iCivics, and the Joan Ganz Cooney Center For Educational Media and Research (Sesame Workshop). He is the former Chairman of the Board of Games for Change and currently serves on its advisory board.